Before I approached them, I had researched the topic. I thought I would find a ton of content on how all of us are one pill away from addiction, or how if you’re a housewife or a teenager with the wrong friends, you’re equally at risk.

But this wasn’t the case. The numbers spoke otherwise, and in many cases, addiction does in fact discriminate.

Statistically, some individuals are more predisposed than others. For example, individuals who are exposed to substance abuse as children are more likely to fall into it as adults, while people with a lower socio-economic status may struggle to access the resources that could potentially stop them from entering full-blown addiction.

But statistics aside, there are other reasons why addiction discriminates. In this New York Times article, Sally Satel argues that personality traits can be a major influencing factor. She explains this using the example of two people trying cocaine at the same time: “One snorts a line, loves it and asks for more. The other also loves it but pushes it away, leaves the party and never touches it again.”

She goes on to add: “Addiction does indeed discriminate. It “selects” for people who are bad at delaying gratification and gauging consequences, who are impulsive, who think they have little to lose, have few competing interests, or are willing to lie to a spouse.”

Satel’s argument doesn’t quite convince me. And neither do the statistics. I do not deny their legitimacy—but I think there is more to add to the discussion.

To find out more, I spoke to three individuals who struggled with addiction in Singapore: two of whom abused substances, and one gambling addict. From them, I realised why despite the numbers, anyone is still at risk of becoming an addict.

I learned that the ‘constants’ in our lives, like personality traits, socio-economic standing and where we grew up, matter only to a point—and that these all go out the window when we face life’s biggest struggles.

It doesn’t matter if you are strong willed, always denying the offer of a cigarette, a line of coke, or a poker game—when life takes a turn and you are struggling, you might find yourself saying yes.

Difficult times don’t discriminate, and it’s during them that our decisions are more crucial than ever. All three subjects I spoke to fell into addiction during moments of turmoil, as a way to cope, to seek love, to solve problems, to fill a void—and they could be any of us.

These are their stories.

NICOLE

Nicole grew up in Singapore, with an European father and Chinese mother, but “I identify as Singaporean,” she says. ”I grew up here and went to a local school.”

She had a really good childhood. She had two sisters she was close to, and she got along well with her parents. But everything changed when her mother passed away.

“I didn’t know how to cope with it,” she said. She started drinking, going out, and partying. Occasionally, she would also smoke weed with her friends.

One night, everything took a turn when the guy who usually brought the weed to the parties “ran out,” and offered her something else instead.

“Do you know what Breaking Bad is?” he asked Nicole.

“No,” she responded.

She wasn’t educated about drugs at all—she was only 15 years old. Nor could she have imagined that a single moment like that would draw her into an addiction to meth—also referred to as ice.

“I had no idea what it was, so I smoked it. I started talking more, being social and feeling awake, and I really liked it. After that I realised I wanted to do more, so I eventually contacted the guy to ask him what it was.”

At that point, she was lonely, grieving, and utterly lost.

“That is when I started staying home and smoking, because I had nothing better to do,” she tells me.

Slowly, things in her life got worse. She lost a few friends, dropped out of school, and to make things worse, her best friend landed in jail.

As her drug use increased, it eventually fell right out of her control, and she soon realised she couldn’t live without it.

“My sister found out at one point so I tried to stop, but I just couldn’t. I spent all my time using, and it became my priority—I needed it. It became everything.”

In no time, Nicole turned into a completely different person. Growing up, she was against drugs. She told me about a time when she was 14 when a friend called to tell her he had done ecstasy.

“I was so upset that he would do that,” she said. But by 15 she was using, and at 16 she was addicted.

Previously, Nicole had kept all her feelings so bottled up, she struggled to grieve for her mother. But ice helped her with that.

“It made me feel like I could finally let out my emotions. I could finally cry. When my mom passed it felt like I couldn’t let it out,” she said.

“But what started as a feeling of freedom soon turned into depression. So I started smoking for the sake of it and it stopped having a purpose. I had to do it to function.”

She tried going to rehab abroad, but it didn’t work out for her. There, she saw all kinds of people seeking help, from “teachers to bankers” and “people who have everything to people who have nothing.”

“It doesn’t discriminate,” she adds.

Eventually, Nicole landed in jail. She admits she might have never stopped if it wasn’t for that.

“It’s harder to stop mentally than it is physically,” she shares.

“Sure, I would get body pains if I tried to stop, but it was the internal battle that was hard. How can you want to stop when you are addicted? When you need it more than food?”

Today, she is clean, and she never wants to go back: “There are so many things I would risk by using again. I would risk my new job, risk going back to jail. There are more bad things from drugs than there are good, and it took me a long time to realise it.”

“At the time, I only had bad things in my life—at least I thought. So there was nothing to lose by using. Now, I have many things to lose, but it took time to value things other than drugs—like my family.”

HELENNA

“You know that saying that a father is every little girl’s hero?” Helenna asks me.

“Yeah,” I answer.

“Mine was a pathological gambler. But I still always looked forward to seeing him,” Helenna says with a quivering voice.

Helenna’s grandmother raised her. She didn’t have a mother, and her father wasn’t available to raise his child. Despite this, she grew up believing her reason for living was to assist her father: “The moment I started working, I was the adult in our relationship. I had no one to advise me on how to deal with him. I became his enabler and codependent. I was his ATM machine. I kept his secrets for him.”

In 2007, Helenna lost her reason to live. “When he died, I died too,” Helenna said. Everything she lived for was gone, and she fell into a deep state of depression.

To make her feel better, Helenna’s friend took her to a private club, hoping it would make for a fun distraction. There, she gambled. “I remember really liking jackpot. It hooked me. I had never indulged in it before because I couldn’t afford it, but now, there was no one depending on me.”

One thing led to another, and Helenna couldn’t stop playing.

It was during those years that online gambling sites started taking off too, “which made me even more vulnerable,”Helenna says. They enabled her by allowing her to “do it in private. I was in a really dark place at the time, so I didn’t want to be in public.”

“I self-sabotaged for about 8 months, and fell deep into addiction. I even took out all the insurance I had bought for my father.”

At first, she justified her habits by saying she was just a casual gambler. But slowly, Helenna realised that it wasn’t helping her. She was only feeling crappier, her money was running out, and no one would lend her anything. “I was at a crossroads,” she said.

“I could either jump off a cliff, or fight. Fortunately, I chose to live. The following day I called the One Hope Centre, got help, and rebuilt my life. A year after that I went back to studying and got my masters.”

Even after seeking help, it took Helenna years to really overcome her addiction. Therapy helped because it allowed her to “connect all the dots in her life.” But that became “overwhelming too, so I turned to gamble when it got too hard. It was my escape from everything.”

“Money to a gambling addict is like heroin to a drug addict, or whiskey to an alcoholic. The moment money is in our hand, that’s it,” Helenna explained.

“But in today’s society, how do you live without access to any money” I asked her. “That is exactly our struggle.

After a turbulent year, Helenna decided to start her own Gamblers Anonymous (GA) meetings, and that is when she committed to changing her ways. “I realized I needed to change my train of thoughts or else I would come across as too hypocritical. People were depending on me,” she said.

Looking back, she still struggles to piece together how it all happened. One thing is certain: growing up in a Chinese family, she was exposed to gambling from a very young age. And because of her father, she knew everything there was to know about it—which made it that much easier to get into.

But Helenna doesn’t think those factors led her to becoming a victim of addiction. “I disliked anyone who gambled,” she said. “I would never date anyone who gambled, it was always one of my first questions on dates. My father was enough as it was.”

Now, Helenna’s GA meetings have grown, and she continues to help other struggling addicts. “It doesn’t matter your status, race, religion, I have seen them all,” she said, talking about the GA meetings she runs.

“I have seen the best lawyers—not ordinary lawyers. I have seen kids from good families, with good education, good jobs.”

Some may have more resources than others and keep up their habits for longer, but eventually: “no matter the addiction, if you don’t do something about it you either lose everything, go to jail or you die.”

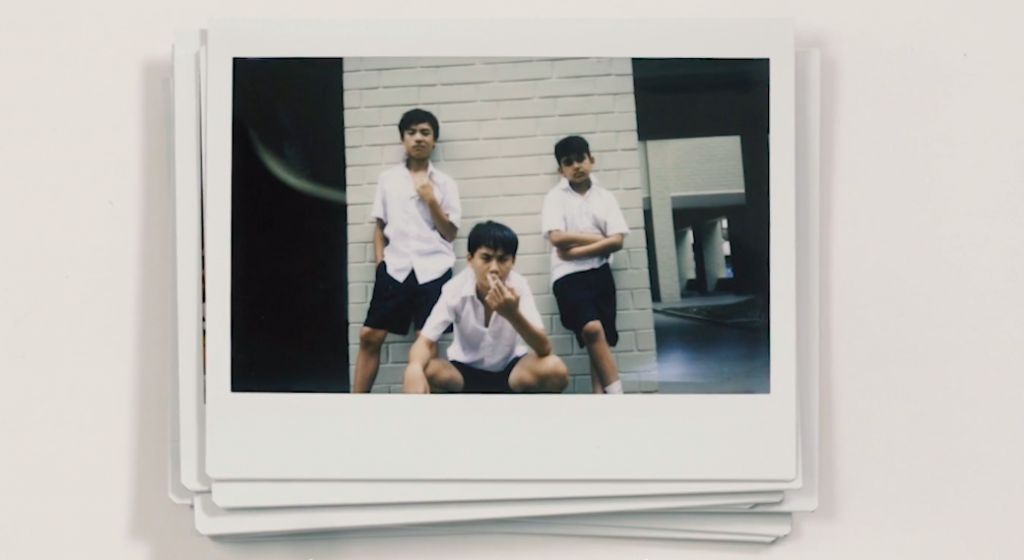

CJ

At a very young age, CJ’s parents gave him away. He jumped from family to family, never truly having a home of his own. With no one paying him any attention, he grew up without rules. This enabled him to get unruly with his friends, and eventually, he got caught for housebreaking.

He got sent to a boys home for kids below the age of 16, and there, CJ noticed everyone would sniff glue at night. “I couldn’t be the only one watching TV while they were all doing that. It wasn’t cool—I wanted to be a part of the group,” CJ shares.

He finally had a chance to belong, so he wasn’t going to let that opportunity pass up.

“These boys were my siblings,” he explains.

“I was on my own. I didn’t know much about drugs when I was really young—all I saw was people around me using, and they were happy. I wanted to feel that way too, so I followed.”

Eventually, when CJ joined National Service (NS), he experimented with harder drugs like heroin. That was when he realised he had an addiction problem: “All my money was finished on this thing, I couldn’t function without it and I had a high tolerance for it surrounding me and my friends.”

“So I started taking more straws and I started pushing to finance my addiction.”

After NS, CJ was caught for housebreaking again in 1993, which got him a two year sentence at a medium security prison. He came out, starting using again, and was put in long term detention for five years in 1998. There he faced six strokes of the cane and isolation for 6 months.

“In 2002, I was released and I was sent to a halfway house to understand more about addiction. There I learned that my problem wasn’t heroin, it was my belief system that was the problem,” CJ told me.

“I started building up the wrong belief system from the age of 16. When other people would keep boundaries and say some things were wrong, I would say they are ok and justify them.”

“That explains so much. For years I told myself that I was only doing soft drugs, and not the hard ones, so I was not an addict. But even there—when it’s not ok, it’s not ok.”

In 2007, CJ was caught for robbery, and sentenced to 5 years in prison and 24 strokes of the cane. Around 2011, he was caught again, only to be released in 2016. It was during that prison sentence that he started to have the realisation that he wanted to get clean.

When other inmates would pass around anti-psychotic pills, he would turn them down: “No, I don’t need that.”

“I looked in the mirror, cried, and said: ‘Why would you let this happen to you? You let people catch you, tie you to a wall and cane you. You are a man of 40-years-old and when people see you on the street they turn away.’ I felt sad for the man in the mirror. Your problems, your mentality, you need to change.”

So he decided to give himself a chance. He came out, joined Narcotics Anonymous, and started to “understand his addiction and his mentality”.

“There are many ways to look at it,” CJ says about his addiction. He can blame his parents for neglecting him. He could blame it on the fact that his adopted family was too busy for him, resulting in him growing up alone on the streets.

But ultimately, “drugs were a means to connect with other people, find friends and find a family. They offered a community and a common ground.”

“In the end, I understood that it wasn’t about taking the drugs away from me, but out of me.”

Have you and/or your loved ones struggled with addiction? Let us know what you think at community@ricemedia.co.