At 6, I didn’t understand any of that; I didn’t even know how to switch on the computer. All my tiny brain could process was that the wired mouse came with a heavy, perfectly smooth ball at its bottom, which I liked to take out and throw at my sister.

At 5, my niece complains if she cannot find an available Wi-Fi network to connect to.

As the geeky uncle, I’m proud of her facility with technology. At the same time, I can’t help but worry for her. Horror stories about technology circulate around my friends and family: the friend of a friend who discovered that a malware had turned on her webcam permanently, the auntie’s daughter who cried because her Instagram photo only had 3 likes, the handsome boy who got catfished on a dating app and thankfully found out before things went any further (me) …

Old people like me merely adopted technology, and are already so vulnerable to it. What about the generation, like my niece, who is born in it, moulded by it— and exposed, from a young age, to all the dangers of it? How are children adopting digital and media literacy in schools even as they deftly navigate touchscreens like little wizards?

First, a quick explanation of what “media literacy” is. According to Patricia Aufderheide, the leading scholar on media studies, media literacy is the capacity to “decode, evaluate, analyse … both print and electronic media”.

To put it simply, media-literate people understand that all sources of media have inherent biases and agendas. Therefore, such people know the importance of thinking critically and cross-referencing against other sources whatever information they come across, whether it’s on an online media platform or something more traditional like television or newspapers .

(In Singapore, “media literacy” includes the abilities not only to curate digital information, but also to create content —but more on the latter later.)

This skill is especially relevant to students today because of the changing relationships they have with the internet and, more broadly, technology.

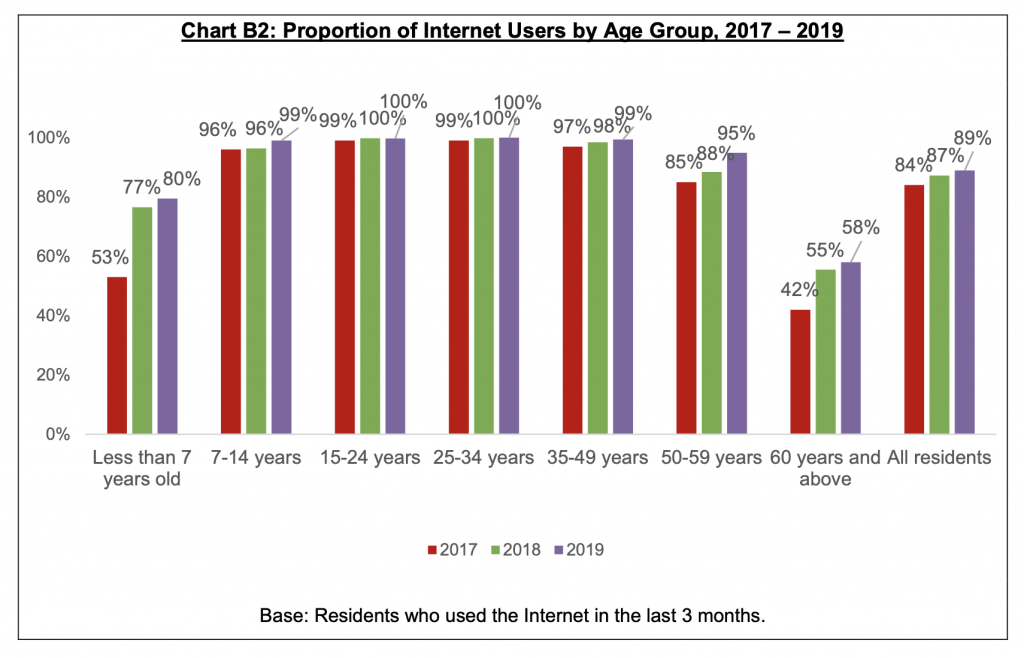

According to Info-communications Media Development Authority’s (IMDA) Annual Survey on Infocomm Usage in Households and by Individuals for 2019, 100% of households with school-going children have access to the internet. Somewhat shockingly (to me at least), in 2019, 80% of children younger than 7 years old (!) are already on the internet, a rise of 27% compared to 2017.

Moreover, with the ubiquity of wireless networks and portable devices, children can now use smartphones to go on the internet wherever they are—at the playground, in the library, or even while queuing to buy lunch, places far from the watchful eye of their parents.

Indeed, the same survey found that, in 2019, 93% of children aged 7 to 14 use a smartphone to access the internet. That’s because the average age a Singapore child gets their first smartphone is 8, a whole 2 years before their international peers.

If we expand the criterion to include other internet-enabled portable devices like tablets, the percentage rises to 100%. That is to say, all children of that age use portable devices to access the internet.

More worryingly, the main use of the internet for children in that age group is instant messaging, followed by watching videos and viewing images, and general web browsing. These are activities that can easily be used for malicious purposes, especially for children at so vulnerable an age.

In combination, these factors put Singapore children at a high risk of succumbing to fake news, becoming victims of cyberbullying, addiction, or many other worse scenarios.

Our schools are, of course, aware of this vulnerability. That’s why media literacy receives such emphasis within their walls. As part of a National Digital Literacy Programme designed by the Ministry of Education (MOE) to ensure students can navigate the digital world safely and confidently, each school, from primary to tertiary, designs and runs its own cyber wellness curriculum.

For example, in School of the Arts, responsible use, and critical analysis, of digital and social media are woven into their main curriculum on design, photography, and film-making. Similarly, Sembawang Secondary School runs an Applied Learning Programme that teaches students media reception skills (“does this website have a bias towards certain institutions?”), media creation skills (“how do I create a video?”), and digital productivity (“How do I use Google Documents more effectively than the noobs at RICE Media?”).

In fact, reflecting changing trends of technology usage, MOE just announced this year that learning about cyber wellness will be expanded and integrated to the current Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) curriculum at all schools. In CCE classes, teachers will guide students through the steps on spotting dangers online as well as avoiding inappropriate content and websites.

On a more macroscopic level, various agencies—specifically, the Ministry of Communications and Information, the National Library Board, the Infocomm Media Development Authority, and the Cyber Security Agency of Singapore—have come together to institute a national framework designed to instil media literacy in Singaporeans, regardless of age.

One result of that is the News and Media Literacy Toolkit launched by the Media Literacy Council (MLC) in 2019. It is targeted at students 13 to 18 and, broadly speaking, teaches them how to spot fake news.

The future is tech.

Quote from a CNA commentary on Singapore’s economy.

I don’t just mean finding the latest music video from Lady Gaga on YouTube. Digital literacy also involves being confident in using technology to solve real-life problems, such as programming robots to automate tasks, or developing artificial intelligence to make sense of complex systems like financial markets.

These are technologies that are increasingly dominating the global economy, yet there is an oddly small pool of talent in Singapore proficient in these areas. And if we want to remain relevant 20 years into the future, digital skills are precisely what we need to invest in.

Enlightenment came, again, from my niece: I discovered that the importance of digital literacy is something our nation is keenly aware of and is, in fact, already addressing in preschools and primary schools across the island.

Back in the 90s, digital literacy took the form of learning to use a keyboard and mouse.

Really.

Because 6-year-old me didn’t know how to turn on the computer, my parents sent me to optional computing classes at my kindergarten to pick up the basics of operating this expensive piece of metal. There, I learnt how to navigate a graphical interface using a mouse and how to save documents to a 3.5” floppy disc. I was introduced to printing, which my teacher immediately regretted, because I proceeded to print—in colour, no less—20 pages of Digimon characters.

Of course, in secondary school, we were taught to use more advanced functions of Microsoft Word, like mail merge—but, really, they were as useful to my life today as learning trigonometry.

And that was the extent of my digital literacy education in schools. From then on, I was on my own.

Which is why I was so surprised—envious, even—when I found out from my niece that she is learning how to program robots as part of her preschool curriculum.

A 5-year-old. Who can’t wash her hands at the sink without being carried. Programming a robot.

Of course, she didn’t put it in quite those terms. Her exact words were: “I tell Bee-Bot to move and it will move.” But when paraphrased as “making a computer perform a specific task via instructions”, that’s essentially programming.

My niece’s adventures being a queen bee is part of a programme known as PlayMaker, a scheme launched by IMDA to introduce young children to technology in a hands-on, screens-off way. In preschools such as My First Skool Serangoon and PCF Tampines Central, Bee-Bot is not only used to teach children the fundamentals of programming, but also integrated into the regular curriculum to make learning about concepts like addition more interactive.

These lucky children. If I had a robot bee to teach me mathematics, today I might not be as afraid of numbers. Or bees.

When my niece graduates to primary school in a few years, the robots she programmes will, correspondingly, graduate from bees to, er, balls.

Just last year, IMDA and MOE jointly developed a coding programme, known as Code For Fun, for upper primary students. It comprises a 10-hour programme that teaches students how to code.

A standardised curriculum is still being worked out, but from the preview that The Straits Times was privy to, it currently involves programming more advanced robots. This time, the guinea pig is a robot named Sphero, which, as its name suggests, is a completely round orb that will dance and navigate mazes at students’ behests. If they programme it properly, that is.

Because of students’ enthusiasm for coding classes, some schools have already initiated their own version of it. At Gongshang Primary School, every Primary 3 student will write, run, and debug programmes using Scratch, a simple coding language meant for children ages 8 to 16.

And as the “For Fun” part of its name suggests, the Code For Fun programme is not examinable, so kancheong parents (I’m looking at you, sis) need not buy an extra carton of chicken essence or whatever their exam arsenal entails.

I mean, I didn’t expect the IT education in our schools to remain stagnant over 20 years. This is Singapore, after all, where our education system is constantly evolving to keep up with the changing world.

So when I take a step back from my surprise and think about this coding bonanza in schools more carefully, it makes sense. Young Singaporeans today, like my niece, don’t need a crash course on how to use a mouse or what a printer is, as I did 20 years ago.

Modern graphical interfaces are so intuitive that even toddlers still confined to their prams are adroitly swiping at iPads to find their favourite YouTube videos. Which is no surprise, considering they were born into the digital world and hence pick up, almost instinctively, the skills to use them. Therefore, they are easily familiarised with the inner workings of the various devices and platforms all around them—laptops, tablets, social media, video streaming …

Thus, what they need is a deeper dive into different skills, like creativity and collaboration, and hard technical skills which allow them to be makers, not just consumers, of digital technology. Hence: the coding lessons, the programming of dancing robots or even flying drones, as students in Zhenghua Secondary School get to experience as part of their ICT (information and communications technology) curriculum.

By 2024, all Secondary 1 students will even have their own Personal Learning Device—either a laptop or tablet as recommended by their school—that will be used to “teach students to use software and devices productively to learn, for work and for daily living, across different contexts”, as Minister of Education Ong Ye Kung explains.

Singapore students are well-equipped with new media skills, which refer to consuming skill and [producing] skill.

Judging from my interactions with my nieces (the older one is 7 this year), they are more equipped than I ever was in dealing with all the digital disruption that seem to crop up every other day.

I consider myself relatively savvy—I use a smartwatch to track my heartrate and sleep, for example—but I can be quite the luddite in some areas. For one, I draw the line at smart speakers. I just can’t get over the weirdness of talking to a slab of metal and having it respond to me.

But my nieces have no such qualms. They yabber away at Siri, Alexa, Cortana, or whatever gender-neutral name the latest voice assistant has.

As this trend continues, it’s inevitable they will eclipse my use of technology. One day, I am sure, they will come home from school and start designing their own blueprints to 3-D-print levitating sculptures or perpetual motion machines or something so innovative it doesn’t even have a name right now.

Or maybe a spork that is actually useful. That’s all I ask for from Singapore’s upcoming generation of digital wizards.

What are your thoughts on how we can better prepare our children for the digital future? Share your opinions with us at community@ricemedia.co.