There are some things in life that are impossible to do: ban newfangled burger creations by fast-food restaurants, release a new iPhone to zero queues, and turn “data privacy” into a sexy topic of discussion. That doesn’t mean we won’t try.

For this story, however, we’re only interested in making “data privacy” something you’d discuss with equal vigour as you do the latest influencer scandal.

For starters, “data privacy” brings to mind stodgy government campaigns doling out trite, tedious, and tired advice about bEinG sAfE tHaN sOrrY. It also evokes stories of naive Singaporeans releasing personal information to scammers, despite clear indications that scam URLs, web pages, and text messages harbour malicious intent.

While these are all valid concerns worth hammering home, related advice tends to fall on deaf ears because most of us inherently understand that our personal data is never truly safe. We are all tethered to some entity in cyberspace or real life; we have all likely shared names, phone numbers, addresses, and bank account numbers with another company or person. Unless we exile ourselves to being hermits, we can’t escape the data-driven reality we live in.

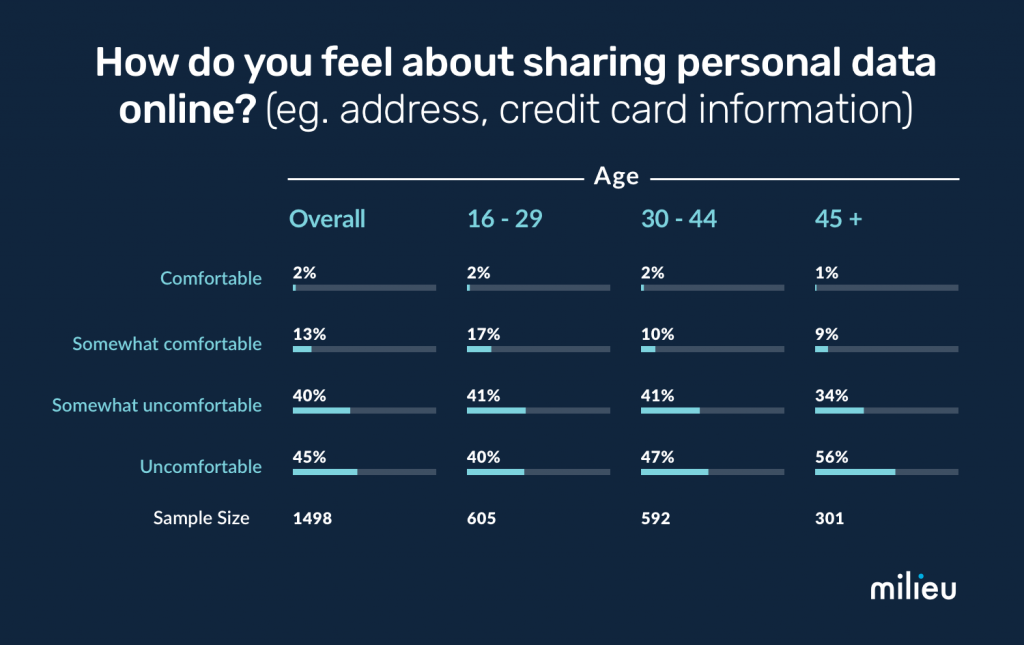

To test our hypothesis that youth might be more cavalier towards sharing personal data online, we conducted a survey with Milieu Insight, an independent research company, among three major age groups (16-29, 30-44, and 45+).

Somewhat unsurprisingly, we discovered that older folk were significantly more likely to “try not to share any information online”. In fact, there was a stark difference between the percentage of those aged above 45 (65%) and those between 16 to 19 (36%) who would avoid sharing their personal information online.

Interestingly, despite the differences, most respondents across the three age groups were still “somewhat uncomfortable” or “uncomfortable” with sharing personal data online.

In other words, young Singaporeans might have grown up knowing it’s inevitable they end up sharing their personal data, but it doesn’t mean they’re desensitised to the consequences of a potential data privacy attack.

In fact, it is precisely their early introduction to the internet and social media makes them hyper-aware.

Even though 22-year-old Huijun acknowledges that nothing can be “truly” private online, he’s “quite concerned” about his data privacy and ensures the sites where he provides his information are “legit”. This means having a URL containing “https” and being subject to data protection laws.

On the other hand, being a woman has made 21-year-old Ethel “increasingly paranoid” about revealing personal data online, leading her to “take more precautionary measures”. She’s aware of how easily technology can be abused through use of secret cameras, revenge porn, hacking webcam or phone cameras, and so on.

While she uses messaging apps (WhatsApp and Telegram) with the ability to encrypt data, she doesn’t believe they’re fully secure, citing a Snapchat fiasco where users who used a third-party programme had their data captured through that service.

Huijun and Ethel might not take extreme measures to safeguard their personal data online, but they remain vigilant about only sharing this data with trusted sources. So at least where basic personal information, such as names, addresses, and credit card numbers, are concerned, the kids are alright.

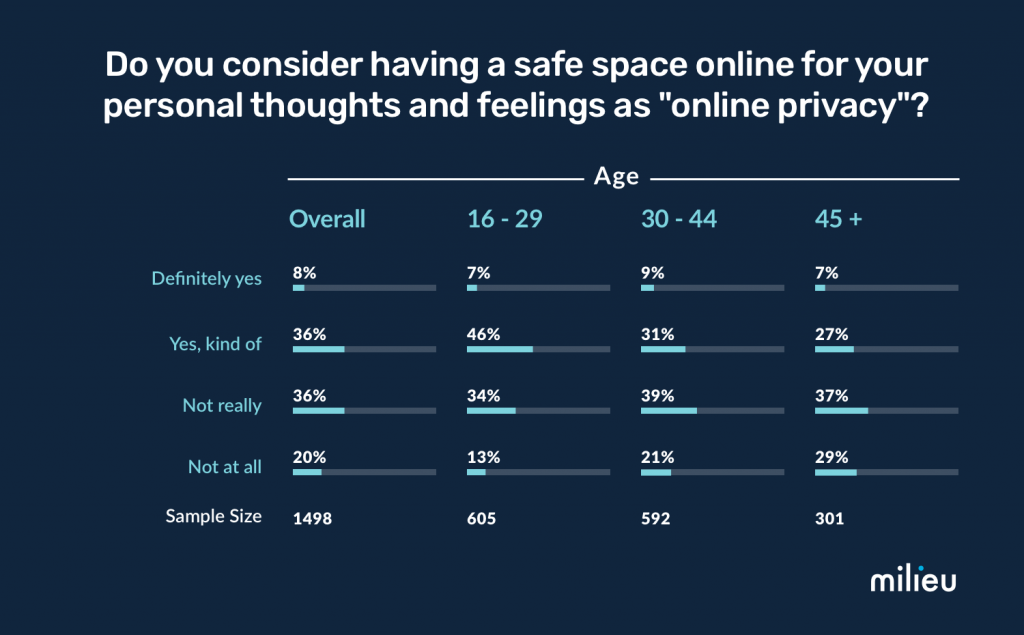

Youth who’ve grown up on the internet might be familiar with creating private social media accounts or blogs to document their inner worlds, granting access to only an exclusive handful of friends.

In the same survey, when asked whether having these safe spaces online for their personal thoughts and feelings constitutes “online privacy”, 53% of those aged 16 to 29 said yes, while only 40% of those aged 30 to 44 and 34% of those aged 45 and above said the same.

These spaces function as private online diaries—a whole minefield of emotional data that’s just as susceptible to leaks as our credit card numbers. With one’s innermost thoughts and feelings, a data privacy attack becomes more about the social than legal ramifications.

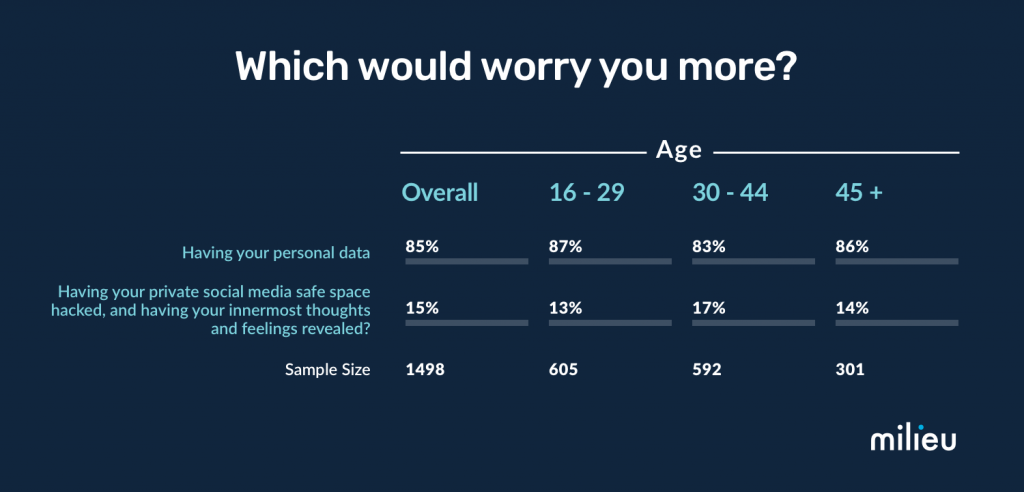

“My personal account is the online persona that can be used against me in a more vicious manner than my personal data. Resolving the ramifications of misused personal data is much easier, because there exists more legal protection for that, compared to someone hacking my account and misrepresenting me,” says 16-year-old Karen (not her real name).

She explains that the “perceived threat or distance of a consequence is more influential than the actual threat” when it comes to determining what worries an individual. And having been a victim of cyberbullying, where she was slammed for sharing her personal thoughts and feelings, her priorities are “subjective and dependent on [her] lived experience”.

Karen is, however, among the minority to share this sentiment.

Or, perhaps the reason is far more straightforward: Singaporeans are private individuals, so their most intimate thoughts and feelings simply remain offline.

Besides, if my interviewees’ answers are anything to go by, this doesn’t mean they don’t keep private social media accounts with a tight handful of followers, don’t share their thoughts and feelings online, or don’t use these private online spaces to express themselves and navigate who they are.

Being private merely means that even the most personal thought or feeling revealed online is still, to an extent, filtered. Nothing online can ever be completely raw or authentic.

I’m usually not one to encourage distrust towards living our lives online. But where data privacy is concerned, it isn’t enough to know that it’s better to be safe than sorry. It’s also about figuring out what “being safe” entails, whether that’s triple-checking a website’s authenticity before giving away your credit card information, restricting your social media follower count to the people you actually care about, or questioning the advice from an article about data privacy on a random website.

TL;DR: data privacy might not be sexy, but neither is having us tell you “I told you so” after you’re scammed—or worse, you’ve had something leaked.