Top image credit: Factually

In case you haven’t been following current affairs beyond the Coronavirus, here’s a quick roundup.

The UK finally split from the EU. Donald Trump’s impeachment trial got spectacularly derailed. And just a few days ago—not that anyone’s celebrating—POFMA reached the 4-month anniversary of its enactment, capped off by the release of the verdict of the Singapore Democratic Party’s (SDP) appeal on February 5th.

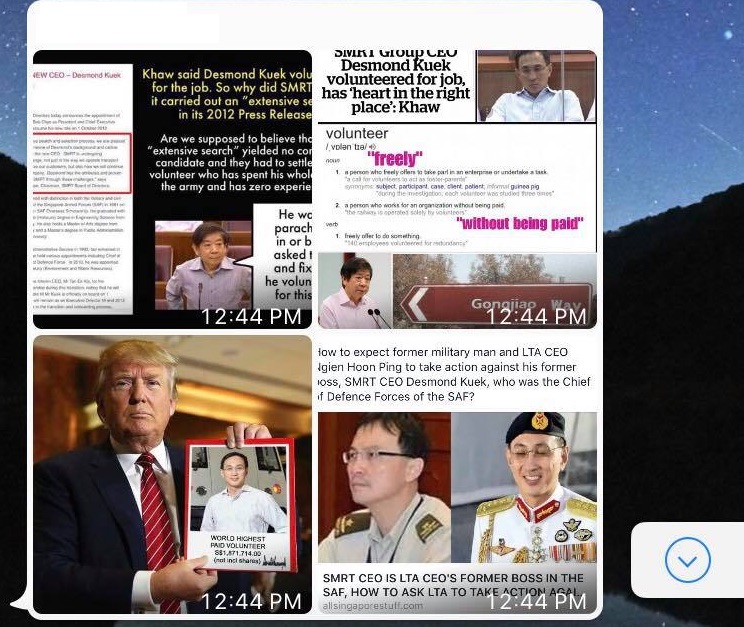

Maybe you believe it was truly an ‘unfortunate coincidence’, as the government has insisted, that POFMA’s first few uses were mostly against Opposition figures. Or maybe you’re convinced that the critics were right all along, and the law is really a convenient tool for silencing dissent.

Whatever your take on this, we should move beyond griping about partisan bias.

The more interesting question, based on POFMA’s first few months of existence, is not whom it is being used against, but whether it is being used in a way that will maintain its credibility.

As a starting point, the government is perfectly within its rights to invoke POFMA against any deliberate online falsehoods that come within the (admittedly wide) remit of the law.

And so far, it has done so in cases where the threat was obvious and imminent (e.g. POFMA episodes 6-9, concerning the various Coronavirus rumours), as well as in ones where it was less apparent (episode 3, concerning the SDP’s statement—now ruled to have been false—that ‘a rising proportion of Singaporean PMETs [are] getting retrenched’).

However, just because a piece of fake news can be POFMA-ed doesn’t mean it should.

The issue is one of proportionality, and on this front, the use of POFMA has been all over the place.

Yes, Brad Bowyer’s claim—which earned him the dubious honour of being POFMA’s first subject—that Temasek invested in Salt Bae’s debt-ridden parent company might have been false.

However, it takes serious mental gymnastics to see this as a threat on the same scale as the rumour that Singapore had run out of face masks in the middle of a public health crisis—the latest piece of fake news (at time of writing) which POFMA was deployed against.

Or recall POFMA Episode 2: the States Times Review’s claim that Minister Shanmugam ordered an arrest over a post on the “NUSSU–NUS Students United” Facebook page.

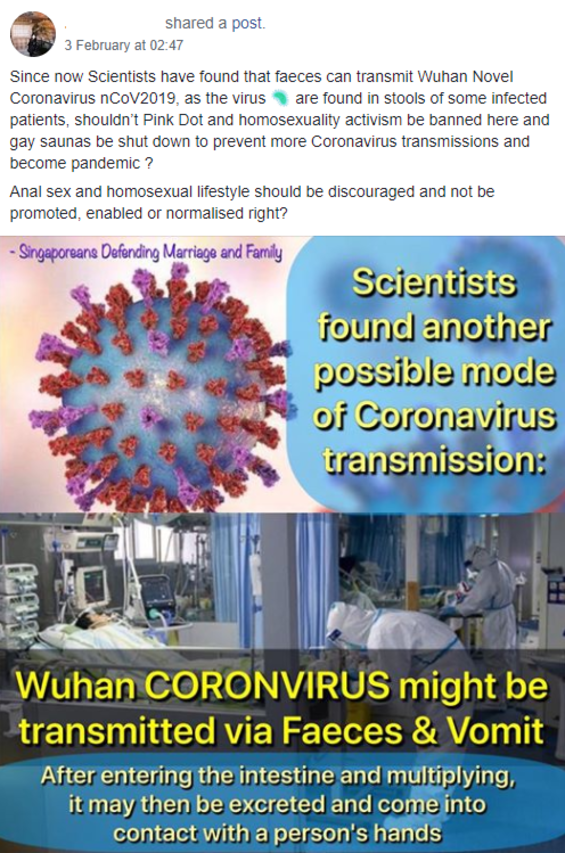

Again, this might have been false. But my myopia notwithstanding, I can’t see how it is any more damaging to the fabric of Singaporean society compared to, say, the misinformation being propagated on various anti-LGBTQ+ Facebook groups.

However, urgency was one of the arguments put forward to justify the scope of the Government’s powers under POFMA. One of the Select Committee’s recommendations, cited by Minister Shanmugam during POFMA’s Second Reading, was that the Government “should have the powers to swiftly disrupt the spread and influence of online falsehoods”, in case they needed to stop a viral post “in a matter of hours”.

Not every use of POFMA has demonstrated this.

While the Coronavirus rumours were indeed tackled in a matter of hours, when the States Times Review was issued a POFMA order on 28 November 2019, the post in contention had already been up for 5 days.

Similarly, Brad Bowyer’s posts were made 12 days before the Minister for Finance issued a Correction Direction.

To this end, POFMA was marketed as an instrument of absolute necessity; one intended for assaults on truth so grave, and which pose such an undeniable risk of harm, that they merited the government swiftly stepping in to protect the public interest.

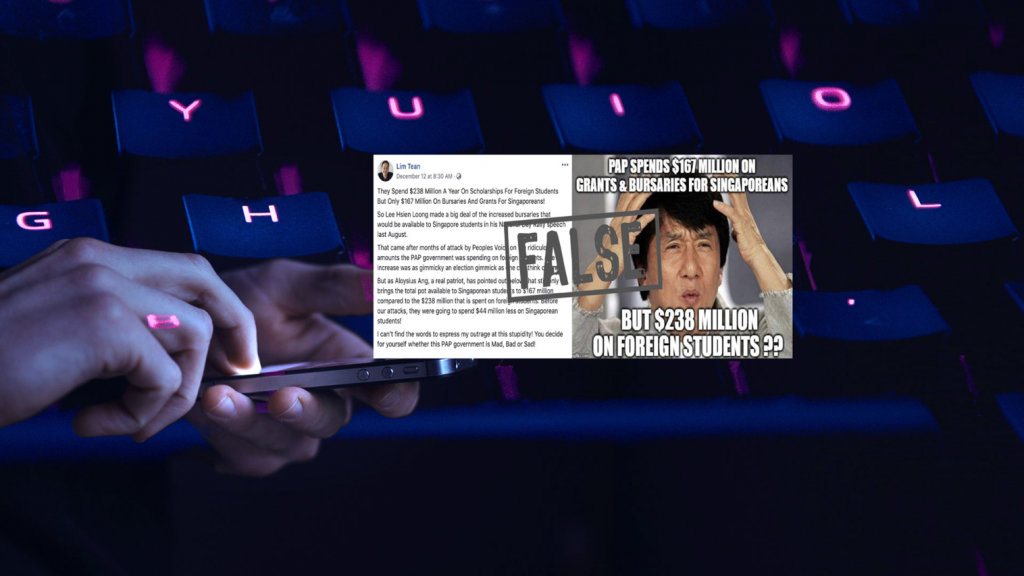

And honestly, did the public interest really need protecting from Lim Tean scrambling his numbers on education spending?

In fairness, since the Coronavirus outbreak began, POFMA has been employed far more sensibly.

The mutters about political bias have temporarily subsided. No-one has kicked up a fuss about using POFMA to quash outbreak-related rumours, because the case for invoking the law was, at last, as clear and indisputable as fact.

This only proves that being judicious with POFMA preserves the law’s credibility. Knowing when not to bother POFMA-ing something is as important as knowing when to.

Unfortunately, the law has been so inconsistently applied that its use going forward is anyone’s guess. Between guessing what is POFMA-able and speculating when the elections will be called, you’d probably have better luck with the latter.

The difficulties exist in substance as well as practice. Even with the release of the SDP judgment, we still have little clarity as to interpretation—when a statement might trigger a correction order—or when a Minister might decide that a POFMA order is the appropriate course of action to take.

What we do know: the SDP judgment clarified that the burden of proving a statement false falls on the Minister issuing the correction order. (The Attorney-General fought back on this point in a different trial the very next day, arguing that the judge had got it wrong. However, the ruling holds for the time being.)

And on the facts of the case, the judge held that there was simply no way the statistics justified SDP’s claim, even if they had tried to pass it off as an opinion.

But as a result, the judgment didn’t reach a conclusion on the issue of interpretation. The Attorney-General’s argument—that if a statement can be construed in multiple ways, and at least one of those is false, POFMA can be invoked even if the other possible meanings are true—therefore lived to fight another day.

This is a terrifying proposition, and one which also seems to run counter to the spirit in which POFMA was intended.

POFMA was, after all, introduced to tackle fake news. It should surely be reserved for cases where the distinction between truth and falsehood is already as clear as black and white. If there is grey at all, then the statement cannot be so outrageous as to justify bringing down the axe.

Meanwhile, as numerous commentators have pointed out, the Government already possesses a number of options for dealing with online falsehoods, all without resorting to POFMA.

They could simply issue an official statement in response. Or write to the statement’s maker or publisher, without calling in the full force of the law, and request that the statement be corrected or taken down.

Either would have been more suitable for the types of statements POFMA was first invoked against.

Sure, hardly anyone takes the time to read official responses, but hardly anyone probably knew or cared what Brad Bowyer said in the first place.

However, by blurring the distinction between a POFMA-ble statement and one which suits a less heavy-handed course of action, the government has arguably created more confusion, not less.

Now that we’ve seen cases where the use of POFMA was clearly warranted, it should, in theory, make it hard for the law to be overused without sounding like the Boy Who Cried Wolf.

Since the Coronavirus outbreak, the trend towards more appropriate use of POFMA has been encouraging. However, the law should never have been used for ‘grey’ cases like the SDP’s, where the falsity of the statements left room for argument, or statements which (however false) were so inane that the need to publicly disprove them was doubtful.

Unfortunately, both egregious and banal falsehoods have been equally POFMA-able in the government’s eyes. And so we now have a law that has been inconsistently applied—one of the surest ways to generate not only confusion, but scepticism as to its efficacy.

So yes, it’s all a mess. Yes, we might need protecting from fake news. But POFMA itself might need protecting from those who would reach too quickly for it.

Thoughts? Send them our way at community@ricemedia.co.