After 20 years at the same company, Charlotte was made senior business manager; Vivienne was an associate professor at the City University of Hong Kong and was the director of many research programmes.

Any glass ceiling was long shattered by these women.

But notice the past tense.

After some discussion within the family, it was decided that her mother would live with Charlotte—she was single and there was space in her apartment—but not before Charlotte spent $5000 of her own money to remove all raised platforms in her house.

Charlotte thus became, almost arbitrarily, the primary caregiver for her mother.

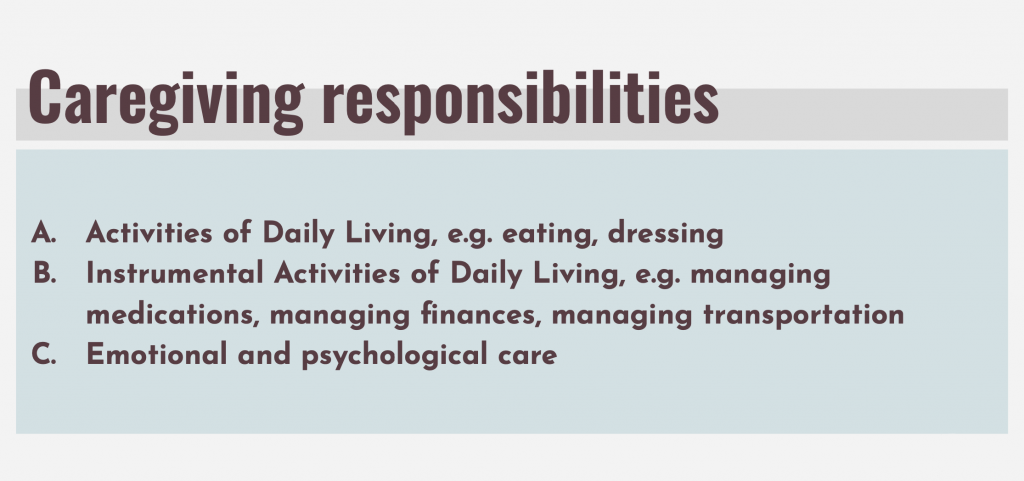

Taking care of an elderly person is not the same as providing care for a geriatric patient suffering from a chronic illness.

When the elderly fall sick, their illness is not localised. It affects their whole body. By this I mean: when a young person catches a cold, for example, they shiver and sneeze, but retain their appetite, mobility, and so on. They recover from it relatively quickly. On the other hand, a common cold, to an elderly person, can lead to complications ranging from pneumonia to organ failure.

Charlotte is painfully aware of this.

“For the elderly, once you’re sick, if it’s status quo, it’s considered very good already,” she remarks in a matter-of-fact way. “But usually, most of the time, it’s going downhill, all directions … every 1 or 2 months, [when my mother has fever], I have to go to hospital with her.”

The haphazard nature of illnesses—who can predict when you are going to fall sick?—meant that Charlotte had to leave the office constantly, often without forewarning, to take care of her mother.

“I don’t know my schedule. In the morning, I don’t know what’s happening in the afternoon. Because my mum, you measure her temperature in the morning, it’ll be okay. 37.5. Then, afternoon 38.5 already. Evening 39. It’s like that lor.”

Thankfully for Charlotte, the management at her company was understanding of her situation. Her seniority and long service at her firm cushioned the impact of her sudden departures from work as well. Still, Charlotte is not blind to the fact that if it weren’t for these factors, she “should be sacked a long time ago”.

“Who will tolerate you?” she asks wryly. “You come in and the next moment you disappear.”

Faced with an erratic schedule and the growing burden of having to care for her mother, whose health was steadily deteriorating, Charlotte decided to reduce her workload and choose early retirement.

“When I was caregiving, I was in a full time job, then half-a-time job, then a quarter-time job.”

“It’s very difficult,” she emphasises. “It’s very difficult to toggle too many things.”

Charlotte was a senior business manager, until she had to give up her career to take care of her mother, full time.

Caregiving is not like a typical office job—or any other job, for that matter—in which you can clock in and clock out your hours. There is no paid vacation, no after-office hours when you can stop checking your company email.

A quick walk to the drinks stall downstairs to take away a cup of kopi?

“No no no—sorry ah today something happened, you have to be around,” Charlotte admonishes.

“We practically cannot leave the house.”

These days, Charlotte survives by buying everything online. I don’t just mean daily essentials like groceries or toiletries. She also relies on online shopping for the medical equipment that keeps her mother alive.

“Changi Hospital, National Health Group, Bion …” she rattles off.

“We have more than 10 suppliers on our hand, you know. Every week, there are deliveries, in 4 or 5 cartons. So the security always asks, ‘How many people are staying in this house?’”

“We tell people my house is a mini-medical centre,” she chuckles self-deprecatingly.

For most of us, medical centres are transient places. We go there expecting a quick consultation, a speedy dispensing of medicine, and a fuss-free discharge. It’s ideal if we don’t set foot into one again, not for a long time, at least.

Charlotte’s medical centre is her permanent habitation. She can check out any time she likes—by watching a show on her phone or taking a long, warm shower after a hard day of caregiving—but she can never leave.

And it’s not as if, overwhelmed by the demands of caregiving, she harbours fantasies of packing everything up and moving to a different country. She simply wants some time for herself, occasionally.

“I’m not saying I must travel and everything. I don’t travel, that’s fine. But the personal time and personal sacrifices … you cannot do as what you like to do.”

Just 2 hours spent at a local cinema watching a newly released movie—that’s a luxury Charlotte can no longer afford.

Charlotte has to take her mother’s temperature, blood pressure, vital signs, and feed her with milk every 3 hours. Charlotte even monitors her mother’s bowels daily. If her stools appear too watery, Charlotte has to tone down on the senna and lactulose, medications that encourage bowel movement.

(Constipation is no small matter for a stroke patient. According to Charlotte, if such a patient forces their motion, they may burst a blood vessel in their brain because of the increased blood pressure it causes.)

“It’s very regimental, like army. Because we have a book to record everything in. When the homecare doctor comes in, he will look at our record, just like in a hospital … we cannot have a blank and say, ‘Oh we forgot half a day’.”

It’s not just passive observation and recording of signs that Charlotte is responsible for. With the help of her domestic helper, she bathes her mother, changes her mother’s diapers 4 or 5 times a day, adjusts the fluid level in her mother’s intravenous drip, carries out suction in her mother’s throat because she often has phlegm stuck inside that she is unable to remove herself.

She pauses, and sighs in exhaustion.

“I’m practically a trained nurse.”

I’m depending on a lot of reserves which I planned for my retirement. But you have to take it out … you can’t help it.

As any woman who performs a double burden knows, even though the chores you perform at home after your first shift in the workforce are emotionally and labour-intensive, you don’t get paid—and often are not appreciated.

In this same vein, everything that Charlotte does at home for her mother comes out of her own time and pocket, and is unseen by anyone else. This puts an incredible strain on her both financially and emotionally.

Each month, she spends up to $4000 taking care of her mother. This figure is inclusive of medication, milk powder, consumables like bandages and alcohol swaps, her helper’s salary, but does not take into account occasional, but recurring, big-ticket items, like the $1000 geriatric chair Charlotte has had to replace thrice already because of everyday wear and tear.

Where does the money come from? Remember that Charlotte had to retire from her job as senior business manager because of the demands of caregiving. She is, therefore, no longer drawing a salary.

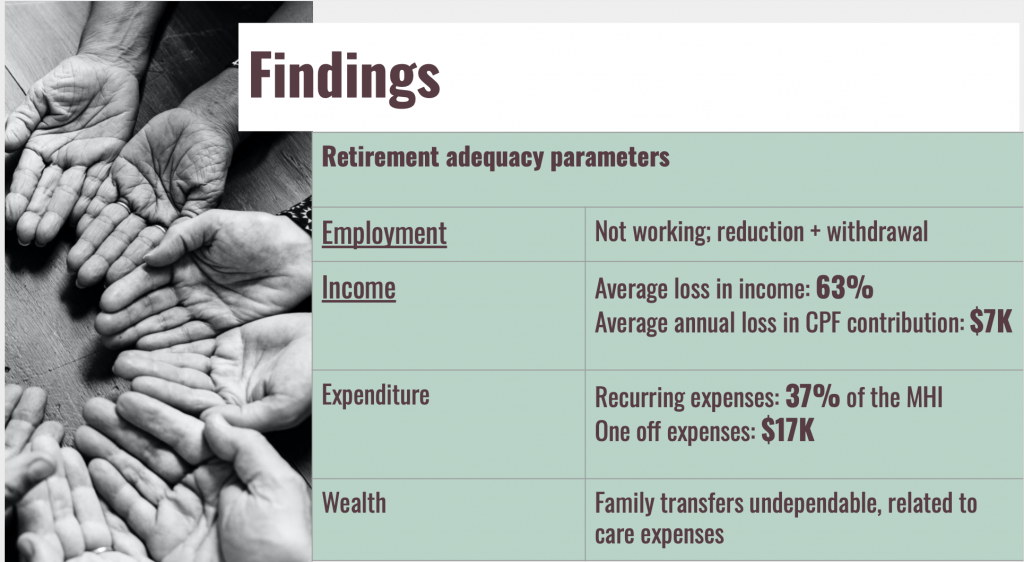

As Charlotte herself puts it, “It’s a double-whammy. I cannot work. I need to spend more time at home. At the same time, the patient is getting sicker. So the income and expenses are inversely related.”

“As the years go by, the gap becomes bigger and bigger, so I have to tap into savings.”

Even though she puts up a brave front, saying, “I’m prepared, I’ve done my sums, I just have to plan my finances very well,” she hesitates when I ask her about her own retirement plans.

“I don’t know,” she finally responds, in a voice stripped of emotion. “I already spend forward. I’m depending on a lot of reserves which I planned for my retirement. But you have to take it out la, you can’t help it.”

“When there is a party or an event, they come to my house to eat and all that. Everything is very good,” Charlotte says.

Everyone in Charlotte’s family is happy during these festive occasions.

Another time when her siblings “are very happy” is when she doesn’t call them.

“The moment they look at my number, they will think, ‘She wants to ask for something. If not ah, ask to help send our mother to hospital.’ When my mother had this chronic illness and started getting sicker, I tell you, whoever can distance, can walk off, they’ll all walk off.”

“Especially financially,” Charlotte stresses, her voice hardening.

Initially, Charlotte and her siblings established a system where all 4 of them contributed a fixed monthly amount to a common pool (about $500 monthly), which was then banked into their mother’s account. All medical expenses would be drawn, by the caregiver, from this account. No allowance is given to the caregiver from this pool.

It started with Charlotte’s younger sister-in-law, who “made a big fuss and queried every single spending”. That family eventually refused to pay.

Thus the house of cards collapsed instantly. Charlotte’s other siblings began pulling out of this common fund because, they claimed, they could not afford to increase their contribution to make up for the deficiency.

But it seems to me that her siblings never wanted to be part of this scheme in the first place, or they would simply have maintained their current levels of contributions instead of ceasing it entirely.

“Everybody fall out. Just me now. In the end.”

“You talk about filial piety, talk about duty, responsibility, I tell you, all nonsense. I can safely tell you all nonsense. Anybody come and talk to me I will tell them to shut up.”

No parent should outlive their child. But no child should see their parent regress to an infantile stage, either. Imagine: the figure who once was your entire world, who taught you what was right and wrong, a warm presence you knew you could always return home to at the end of the day, regardless of what happened. This figure, reduced, today, to an incapacitated body who passes motion in their diaper four times a day.

Imagine the emotional turmoil and psychological strain of seeing your hero and your world still in front of you, but just an empty husk. Who wouldn’t break down?

The caregiver can’t.

“I cannot be emo. If I get so caught up with something, I will forget the things I need to do while caregiving.”

Despite all her hardship and sacrifices, Charlotte doesn’t begrudge her current situation. It is her mother whom she is take care of, after all.

“In the end, it’s unconditional love,” Charlotte says, her voice, after an hour of restraint, finally cracking with emotion.

According to “Making Care Count”, a research report on caregiving that The Association of Women for Action and Research (AWARE) released this October, 66% of their survey respondents experienced a change in their employment status and income because of their caregiving responsibilities. In numerical terms, the average loss of personal income, as a result of the change in their employment status, is $56,877 a year, or almost $5000 a month.

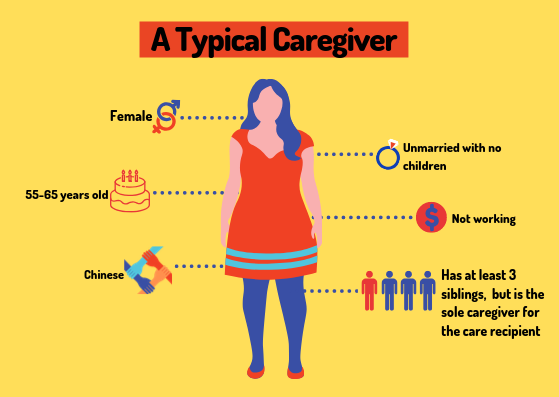

Moreover, the typical profile of a caregiver is overwhelmingly an unmarried woman in her 50s to 60s.

These factors place additional strain on the caregiver: as a single person, she usually has fewer emotional and financial resources to draw on; as a woman, she tends to be earning less in the first place (the gender wage gap is somehow still a thing in 2019 Singapore); as an individual in her 50s to 60s, it’s not as if she’s still brimming with youthful health herself.

Still, one aspect the report touches on only briefly is how our health institutions sometimes aggravate, not alleviate, the burden of care these caregivers undergo.

By most accounts, Vivienne’s caregiving experience is not as painful as Charlotte’s. (That said, I’m not suggesting that it is possible to quantify or compare the emotional and financial strain each individual caregiver feels.)

Like Charlotte, Vivienne had to sacrifice her career for the sake of her aunt—who has since passed on—and her mother, who is celebrating her 95th birthday next month. Originally an associate professor at the City University of Hong Kong, in 2010, Vivienne gave up her full-time job to return to Singapore permanently and take on a caregiving role.

Fortunately for Vivienne, she transitioned to a home-based job as a research writer, so she has not lost her income entirely. Additionally, she receives support, both financially and emotionally, from her husband and siblings.

Most crucial of all: Vivienne’s mother is, remarkably, still lucid and sprightly.

“I am still teaching voice [to some people],” she tells me proudly. “They have been my students for some time, but I do have 1 or 2 new students. I just do my best—and this a good thing, the doctor told me, that I can do still something.”

“I found that my caregiving experience is like bridging the gaps. The system is just …” Vivienne sighs before finishing her sentence, “… so exhausting.”

Among the many grievances about Singapore’s inadequate geriatric healthcare system that Vivienne enumerated during my talk with her, 4 incidents stand out to me.

Vivienne’s aunt, whom she was taking care of until her aunt passed away in 2018, suffered from asthma, so she required an oxygen machine to breathe properly. During a consultation held at a polyclinic, Vivienne naturally brought along her aunt’s oxygen machine. But she was told by the polyclinic that she wasn’t allowed to use the electricity there to power the oxygen machine.

Her aunt’s experiences as a patient in National University Hospital (NUH) were equally bewildering. Once, a nurse was “so rough with her [aunt]”, Vivienne says, that “the nurse fractured her [aunt’s] bones”. And it was only after Vivienne complained that her aunt seemed to be in distress that an X-ray was conducted, revealing the fracture.

Vivienne also recounts a period when her family thought her aunt was on her deathbed, and so decided that their helper should stay by her bedside in NUH should anything happen in the middle of the night.

Something indeed happened, though it was not what they expected.

First, some context: Vivienne’s aunt is totally blind, bed-bound, and physically incapacitated. It was a good thing, then, that her family’s helper was present by the bed of Vivienne’s aunt, to serve as her eyes and hands. Vivienne says the family found out that the nurses in the ward would “put the food down, go away … and then they take the tray away” a while later.

Keep in mind that her aunt would have been unaware that food was served because she was blind, and would have been unable to eat at all because of her physical incapacitation.

“I tell you, the helper saved her life, she had an extra 4 or 5 years, as a result of that.”

Vivienne doesn’t blame the nurses for negligence. She knows how overworked and overstretched the nurses are—at the time her aunt was warded, she thinks there were only “2 nurses for a few wards”. It got so bad that “the nurses [were] grateful for the helpers, who were sleeping on the floor or sleeping bags at the C-class ward”.

The experiences of her mother at the hospital weren’t an improvement from her aunt’s, either.

At her advanced age and being hard of hearing, Vivienne’s mother needs a hearing aid. So Vivienne bought a hearing aid that, according to her, cost $3000 from NUH before subsidies. But the hearing aid didn’t seem to work; her mother still couldn’t hear properly. Thus, Vivienne consulted a private audiologist who, after examining the hearing aid Vivienne bought, found out that it was an obsolete model that was no longer being manufactured.

“It’s very unethical for them to have shoved it onto the public hospital—and [unethical that] the public hospital is selling it still. Why are people being saddled with these obsolete equipment?” Vivienne exclaims in exasperation.

(NUH has responded to these allegations. Their response is appended to the end of this article.)

The sense of frustration grows so pronounced that Vivienne’s mother—who has hitherto been calmly listening to our conversation, interjects in disgruntlement: “The young doctors today should be better, in mannerism. The first thing they ask is, ‘you speak Chinese?’ And they are shouting. It’s very rushed.”

That said, not all of Vivienne’s experiences with the geriatric care system are scenes straight out of absurdist literature.

She has effusive praise for a nurse from NUH who proactively paid them a house visit after her mother was discharged from the hospital. Upon seeing her bedridden aunt, the nurse even took the initiative to arrange for a doctor from Thye Hua Kwan Moral Society to pay them house calls at a subsidised rate.

A Dr James Tan at NUH’s Pain Clinic and the recently opened Medicine Clinic at NUH, which Vivienne says “doesn’t push you around to another department” even if the patient’s ailment doesn’t fall squarely into its purview, also earned Vivienne’s commendation and appreciation.

Charlotte, too, laments that “the eldercare system in Singapore is terrible … the government talks about advancement and automation, but the human aspect of elderly care is still very much lacking.” This perspective is borne out of her own struggles with another public hospital in Singapore; we are, however, unable to publish her allegations because she was not comfortable going on the record.

What can we, as a society and as a political entity, do to help caregivers?

Well—who better to give suggestions than the caregivers themselves?

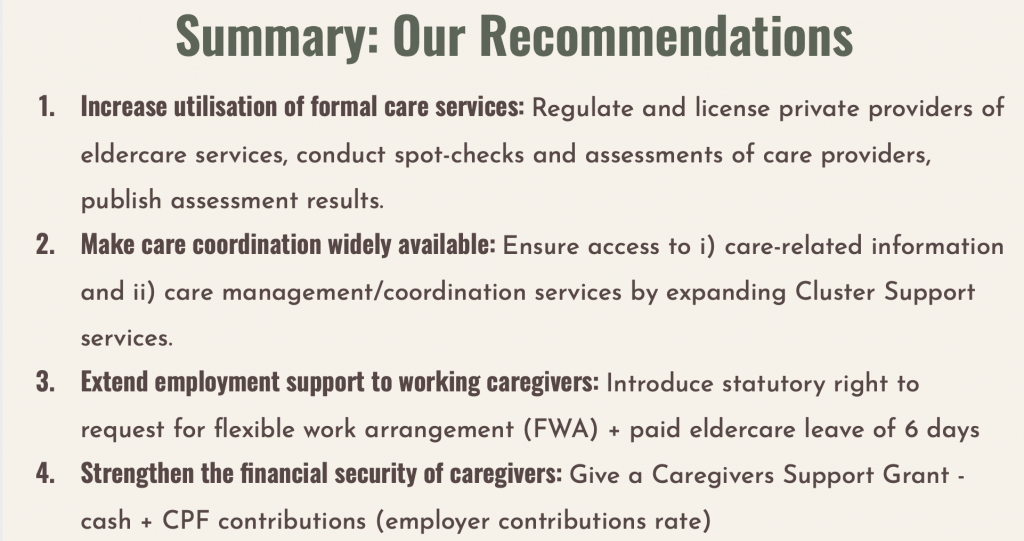

Vivienne simply wishes that there were a better overarching agency—other than the Agency for Integrated Care, which she says was of no help to her—that can guide caregivers and co-ordinate matters.

“The nurse that we had from NUH— somebody like that who knows the system— if I had somebody like that to go and consult, I wouldn’t have to grope around in the dark. Everything is in little pockets, islands, they are not connected at all.”

Charlotte, on the other hand, has 2 requests.

“The government is very funny. They give [the] elderly subsidies, but how about the caregiver? It’s because of the informal caregivers like us, we really help to cut down the bed crunch in hospitals.”

She adds, “The government doesn’t see the bigger problem: they never fully support the caregiver. I would say, we should be given an allowance. Using me as an example—I know that other people also suffer in silence because they’re not as vocal as me—how can we work and earn an income still?”

Finally, “my other request to the government is, for a sick patient with chronic illness like this, the government can do an auto-swipe from their children. From their CPF account or whatever account. Based on their income. Every month they can swipe into the patient’s account. Not the caregiver’s account ah.”

“We must have a system to send a message to the children: ‘Look, you have your duty and responsibility.’”

Caregivers, removed from society physically and professionally, don’t often factor into our muted national conversation on poverty either.

Yet, the typical caregiver—who is, to reiterate AWARE’s report, a 56-to-65-year-old single woman who has left her job and has experienced a loss of income—is one of the most vulnerable groups of people in society.

And this is not even taking into account the fact that they are caring for an even more vulnerable group of people.

When, then, will we finally start caring for the caregivers?

We take Ms Wee’s concerns about her aunt and mother’s experiences at NUH seriously.

Based on our records, during her late aunt’s admission from 30 Mar to 9 April 2018, Ms Wee was concerned that her aunt had suffered a fracture. The doctors had explained to Ms Wee that her aunt had longstanding poor bone health since 2013 and these fractures were present, based on medical records review, prior to her admission. The family indicated at that time that they were appreciative of the team’s update and care, and were satisfied that all their questions have been answered.

With regard to the hearing aid that Ms Wee purchased for her mother in June 2016, our records show that Ms Wee paid a subsidised rate of $300, not $3,000. The model in question was not due to be phased out at the point of Ms Wee’s mother’s evaluation and subsequent fitting in June 2016. The model was prescribed to patients till December 2017. Service support for the model is available until 2022.

As a number of the issues raised took place several years ago, Ms Wee was unable to provide us details that can help us conduct a complete investigation. We have left the lines of communication open for future follow up if more details are available. We thank Ms Wee for her feedback.

We have since amended this sentence to “At her advanced age and being hard of hearing, Vivienne’s mother needs a hearing aid. So Vivienne bought a hearing aid that, according to her, cost $3000 from NUH before subsidies” to reflect NUH’s response.

In conjunction with the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty on 17th October, we have teamed up with local NGOs to raise awareness of poverty and inequality in Singapore. Check out the Stand Together Festival for more information.

Have a thought after reading this story? Let us know at community@ricemedia.co