When I first heard about a mysterious pneumonia emerging in Wuhan at the end of December, I shrugged off the inkling that this might grow into a Sars-like pandemic. China’s experience from 2002 would have contained the spread in no time.

As I sat on the plane headed back home to China, watching The Farewell and relishing my many plans over Chinese New Year, little did I know that the pandemic would transform the otherwise festive occasion into uneasy chaos.

Now, several months later, as China cautiously emerges out of lockdown, Singapore is knee-deep in its battle against the virus. During these 2 months of the ‘circuit breaker’, I’ve found myself repeatedly dragged back to the listless spring festival I spent at home, under lockdown.

The Covid-19 pandemic has launched the world into upheaval, and more changes are yet to come.

I live in Shantou, a coastal city famous for its delicious food and tedious rituals and traditions. About 8 years ago, I came over to Singapore to study. As Singapore typically allocates two days off for Chinese New Year, I don’t manage to spend holidays back home very often.

So when I realised that this year’s calendar promised a long weekend, I went ahead and booked the tickets home. I just wanted to relive the boisterous, bustling holiday experience with my friends and family.

But then Covid-19 struck. The night when I touched down in Shantou, the Chinese health authorities formally declared that the virus was capable of human-to-human transmission. Following the announcement, my hometown shut most shops, restaurants, beaches, mountains, and even temples, which was a big deal given how religious Teochew people are.

I was stunned. We only had two 29ml bottles of hand sanitiser from Miniso, and no masks. By the time we went out to look for these items, shelves were all swept clean.

The panic buying did not improve as the Shantou government announced a partial lockdown on the second day of the Chinese New Year. On WeChat, pictures of people carrying bags of rice on their motorbikes went viral. Most called it pure stupidity, since the rainy weather during the holiday would not have allowed perishables to stay fresh, but there were also small groups voicing regret at not joining the rice hoarders. Luckily or not, as the government made a sharp U-turn and cancelled the order later that day. Now, we could all laugh at the ‘rice-stocking idiots’ equally.

On the night of the policy reversal, I ventured out for the first and the only time to meet my friends and hunt for masks amongst the few shops with lights still on. On our way, we saw the town’s public square. Situated between an ancient pagoda and a popular cinema, the plaza should have been teeming with screaming children, dancing elderlies, and hopeful street hawkers with their noisy, flashing, spinning gadgets.

My cousins had bought fancy light sticks and accessories from Taobao earlier, hoping to capitalise on the huge crowd to earn some extra cash during the festive season. Despite the news on the Covid-19 outbreak, they still set up a stand at the plaza on Chinese New Year—the audacity—but the security swiftly chased them away. As we stood there shivering in the cold, only a handful were strolling around the plaza, alone.

Elsewhere, the few masked individuals still out on the streets all looked like they were hurrying somewhere, unwilling to spend one more minute outside. It seemed like the government’s shifting positions on the lockdown, coupled with viral tips shared on social media on how to get your stubborn family members to wear masks, had produced a real impact. No fireworks, no crowd; the city was eerily hushed, with red Chinese knot-shaped lamps glowing ominously in the dark.

Staying at home didn’t promise peace of mind. I was overwhelmed with all sorts of information on social media, ranging from the escalating death toll to the alleged government cover-up, from calls for help across China to conspiracy theories on the virus origin. A friend commented that since the reported Covid-19 cases would climb up a bit more every time he woke up, he should just not sleep, and the infected headcount would stay the same. While we had a good laugh, it was true in the sense that we all wished the disease would go away. Back then, peaceful Singapore where all seemed well was like an alternate universe, too good to be true.

Given the limited official updates on the Covid-19 spread in Shantou, people became desperate for any information to get a bearing on the situation. On one hand, the quest for data spawned multiple online platforms that allowed you to key in the train or flight number you took back home, and check whether your carriage or airplane already had known infected cases.

On the other hand, rumours began surfacing in WeChat groups, usually in the form of a badly pixelated video clip showing ambulance cars at an apartment, followed by an authoritative message on the block and room number of the suspected Covid-19 patient. I witnessed a “POFMA” moment when a person in my mother’s WeChat group claimed that Block 9 in a particular condominium just confirmed a Covid-19 case, and someone who lived there revealed that the complex only had six blocks.

It was soon revealed that most of the cases in my city were imported from Wuhan, the epicentre of the epidemic, fuelling a wave of anti-Wuhan sentiment. At a hotel near my house was parked a car with a license plate registered in Wuhan. After numerous anonymous reports made to the police, the car owner had to put up a notice at his car window, stating categorically that he had not been to Wuhan for years.

Meanwhile, an excel sheet started circulating on WeChat. It contained personal information of all the local residents who had just returned from Wuhan. No one knew who compiled the list, nor how that person had access to those phone numbers and home addresses, but no one seemed to mind.

Looking back, those times seemed tense and confusing, the exact opposite to a supposedly festive, joyous Chinese New Year.

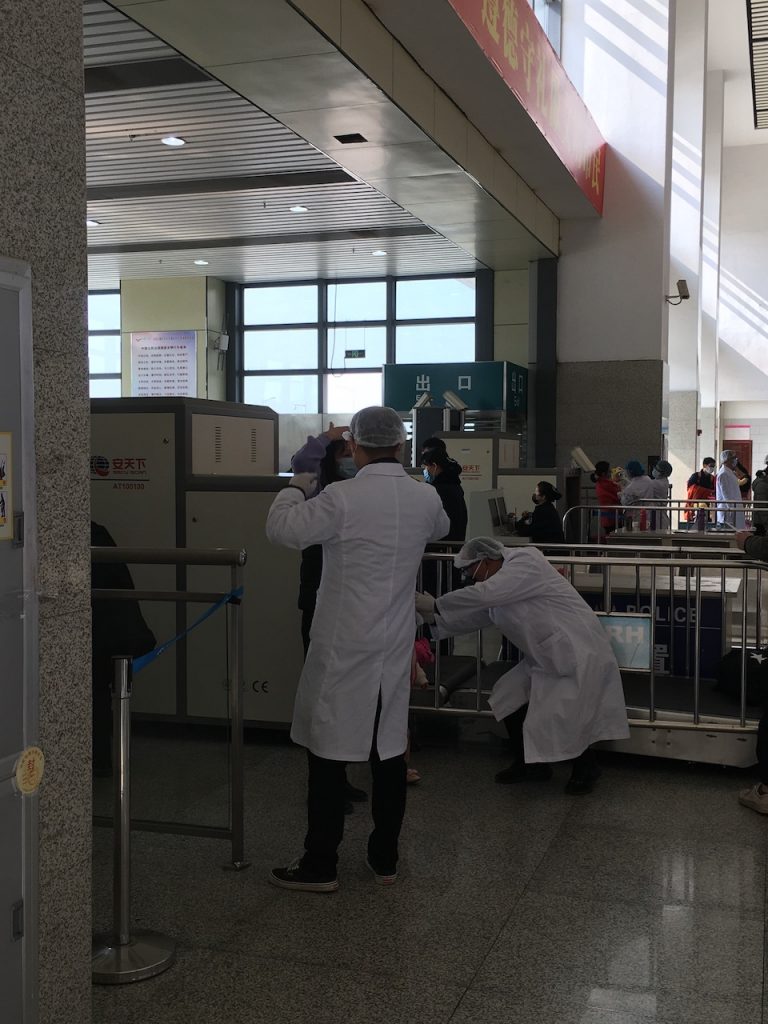

To save money, I devised an elaborate plan to return to Singapore. On Jan 29, it would first take me a 45-minute drive to reach the nearest railway station to board a train to Hong Kong. Upon reaching the city, I was then supposed to hop on the Airport Express subway, before catching a flight back to the Lion City. I had it all planned out to the minute, but Covid-19 added much anxiety to my schedule.

With more imported Covid-19 cases emerging in Hong Kong and Singapore, both cities started tightening border controls. While Singapore did not ban long-term pass holders from entering, Hong Kong sought to minimise transiting travellers and the risks posed to its population, amid talks of banning mainland passengers from transiting through its airport altogether.

Jan 28 was particularly excruciating for me, as I anxiously awaited news from Hong Kong. At around 5 PM, the special administrative region’s government announced it would cut mainland flights and close the railway from Jan 30 midnight. I heaved a huge sigh of relief.

Just For Precautions

One fear that I always had was, what if I’m an asymptomatic carrier AND a super spreader? I was worried that I might have contracted the virus on the way home in the crowded plane and train, and would pass it to my family. So either way I was prepared to err on the safe side, and self-isolate for 14 days when I came back to Singapore.

But before I could start my Leave of Absence at a designated hall in Nanyang Technological University (NTU), I had to go back to my hall room to retrieve some personal belongings. My new roommate wasn’t in then, but a pillow and a router were lying on his bed. The next morning, I received a phone call from my hall.

After confirming that I was now being isolated at another hall, the lady was about to hang up when I casually asked why she had called me. It turned out that my roomie somehow guessed that I returned to China during Chinese New Year, and applied to change to another room. He seemed eager to leave, as he asked the hall office to simply clear his belongings in the room.

When I asked for the reason, it felt like the caller was thinking about how to phrase it nicely, and I just blurted out: “They scared is it?”

I couldn’t remember the lady’s exact reply, but I thought I heard some ambivalent “hmms” and “umms” and awkward chuckling. I didn’t feel targeted or anything. After all, this was the novel coronavirus, and we were all just trying to take precautions.

That said, I never quite saw the same kind of ghost town situation in Singapore. Despite Chinese New Year being the most important festival in my hometown, no one there ventured out to enjoy hotpot, exercise, or visit relatives. Singapore adopted a different approach, where life was kept as normal as possible. As much as I understood the government’s rationale, seeing people jovially going to clubs, family gatherings, and mass events still bewildered me. What happened to kiasi Singaporeans?

On the other hand, the proverbial kiasi Singaporeans have surfaced in frantic shopping at supermarkets, or by ignoring professional advice and sharing dubious news on Covid-19 deaths. I never thought that I would witness the same kind of panic buying and desperation for information in Singapore as in my hometown. After all, the Singapore government was arguably doing much more than my city, updating daily numbers, ensuring steady supplies, and conducting contact tracing diligently. So shouldn’t Singaporeans feel safer and calmer? I never quite figured out the answer to my question.

Uneasiness has sunk in, providing the perfect culture for prejudices to mushroom and prevail. Whenever I chance upon comments on social media blaming the Covid-19 surge on migrant workers, I am instantly yanked back to the start of the year, when the Wuhan-registered car was repeatedly reported, and the Wuhan returnees’ personal particulars were freely floating around online. I didn’t find out what happened to those people on the excel sheet, but it couldn’t have felt too great to have the entire town watching, judging, and commenting on you.

Hall Alone

As Covid-19 spread in Singapore, while my hometown of Shantou saw zero increases for the past 3 months, my parents were getting more worried. They tried to read up on Singapore news, habitually checked in with me on the number of cases for that day, nagging at me not to go out at all. On the whole though, I wouldn’t say they were super anxious. After all, I have already lived in Singapore for eight years now. While infected cases from migrant worker dorms are expected to remain high, ‘local community transmission’ seems to be under control.

That said, I do call my family much more often than before. As much as I should be used to it, being confined to my room gets very lonely. My hall has few residents left, since NTU ordered all hall residents with a local address to move out. At night, all I can hear is the music playing on my computer and the insects chirping outside my room. Other than the few words I exchange with the aunties and uncles at canteen stalls, I don’t really need to speak at all. So calling my family is arguably the only time in the day when I can relive what talking and joking and laughing feels like.

I am staying in Singapore during this summer break, so the travel restrictions Singapore and China have put in place do not really bother me. And to be honest, I wouldn’t want to risk my life flying around as well. But to some of my friends who planned to go back, it really bummed them out when NTU warned that those who still decide to return home risk serving one or two semesters’ LOA, during which the school would not provide e-learning or any scholarship stipend, and their student visas would be suspended. Nevertheless, we all have to deal with the situation as it is.

Sometimes I look back on the few days I spent at home in January. Wet, chilly winter. Everything turned upside down by the epidemic. But back at home, it was still warm and cozy. My sister and I played charades, poker, and sang karaoke. We lit sparklers on the balcony and watched them shimmer in brilliant reds and golds and greens. For one moment it looked like any other Chinese New Year, complete with family, fireworks, and fun.

But it wasn’t, and it won’t be the same any more. The Covid-19 pandemic has launched the world into upheaval, and more changes are yet to come.