Disclaimer: RICE does not endorse or support any political party in Singapore.

We’ve also witnessed a diverse outpouring of online commentary. Plenty of regular Singaporeans have started creating original GE-related content, posting observations and analyses, tapping on everything from marketing know-how to Facebook interaction data.

Though these commentaries vary in terms of depth—as expected when you give someone a mouthpiece on a digital platform—a handful have presented very astute observations that made us wish we’d thought of it first.

Here is a list of our favourites.

This list wouldn’t exist without Joel Lim, whose breakdown of the brilliant Workers’ Party campaign video went viral.

Joel draws on his PR and events background to analyse the messaging in the WP video. Though he does find the opening, in which Pritam Singh uses the dark/light analogy to explain why we need balance in parliament, a little “tacky” and “dramatic”, he finds that the video does a really good job.

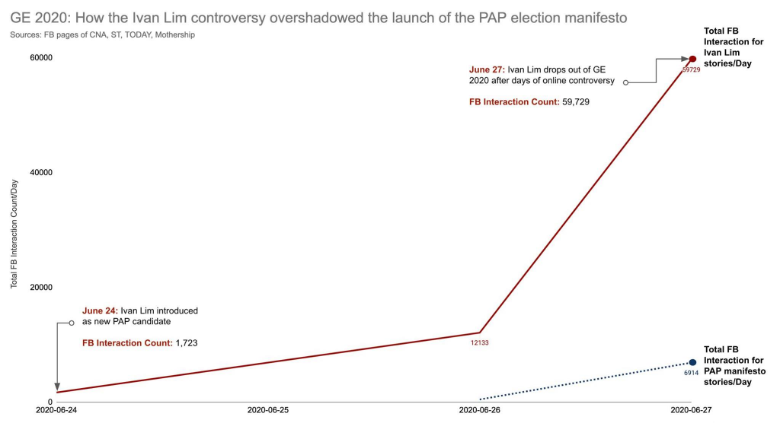

It felt like everyone and their mother was talking about Ivan Lim last week. But just how widespread was the Ivan Lim incident?

You can find out by counting off how many times his name shows up in your family chat, or, like Chua Chin Hon, you can turn to Facebook interaction data.

On June 27, when PAP’s manifesto was released, the Facebook interaction count for Ivan Lim-related stories far outstripped interactions with PAP’s manifesto. In fact, the interaction count for Ivan Lim-related stories was nearly nine times more than that for PAP’s manifestos, hinting at why we may have eventually seen him drop out of the election.

Yes, everyone and their mother was talking about Ivan Lim last week, and we have data to back that up. (Disclaimer: limited data sample size, which may or may not include people’s mothers.)

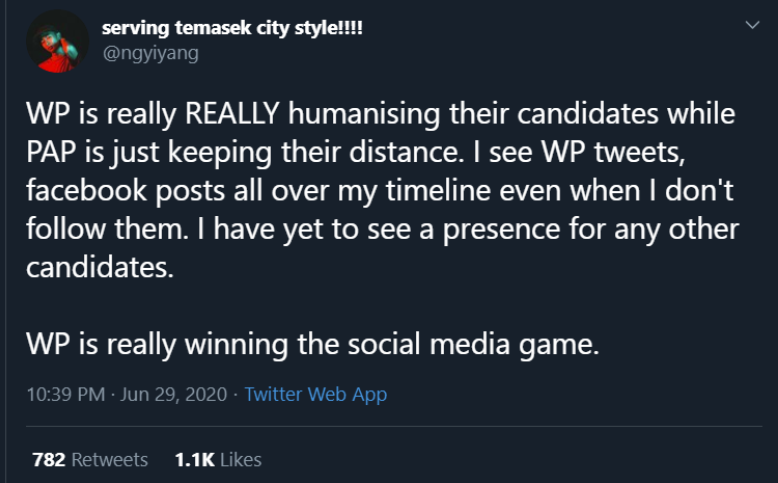

To really drive home the point about the importance of social media in GE 2020, just take a look at the WP’s online presence.

In a Twitter thread, Ng Yi Yang notes just how important social media has become in this election. He observes that the WP is making a concerted effort to humanise their candidates by establishing their social media presence, such as by having candidates upload pictures from their walkabouts. Their Facebook posts and tweets also appear on his timeline even though he doesn’t follow their pages—a sure indication of expertise in Facebook ad targeting.

In fact, 26-year old Raeesah Khan from the WP, who’s set to contest in Sengkang GRC, grew her account from 0 to more than 2000 followers (nearing 3000, as I write this) in less than a week.

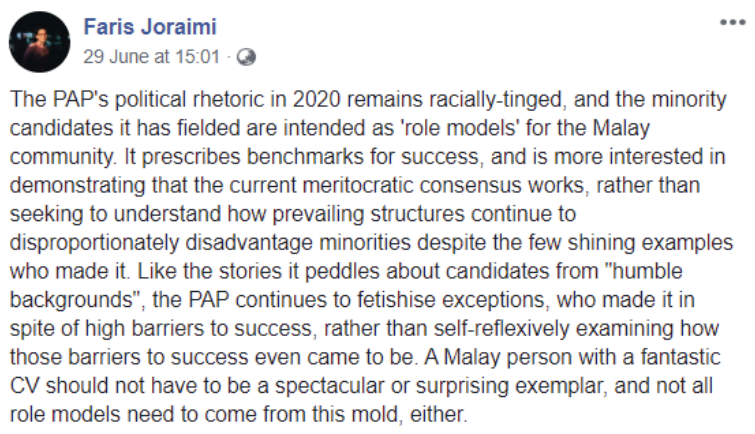

On June 29, PM Lee described PAP’s Malay candidates as role models, which History undergraduate Faris Joraimi noted was a “racially-tinged” political rhetoric.

This narrative is similar to how PAP continues to emphasise that its candidates come from humble backgrounds—lived in a rental flat, father was a taxi driver, everyone worked super hard to make ends meet—and succeeded in spite of barriers to success. Yet, as Faris astutely points out, all this is done without “examining how those barriers to success even came to be”.

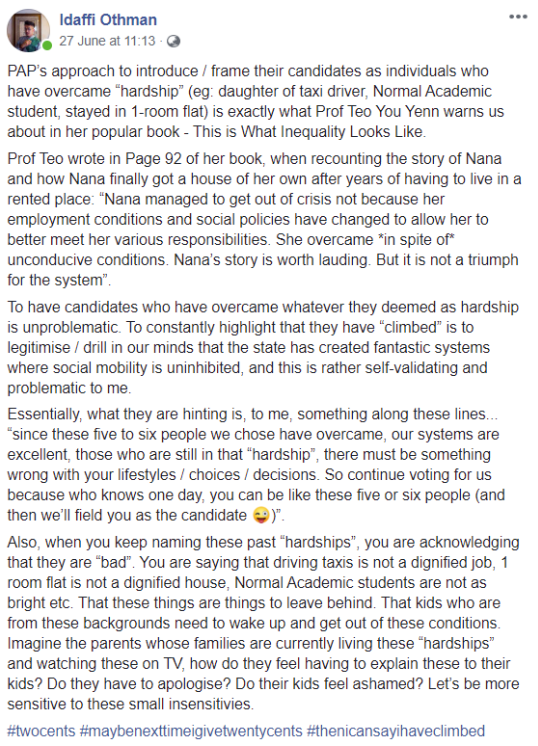

PAP’s framing of success and hardship was also brought up in a Facebook post by Idaffi Othman, who drew comparisons with Teo You Yenn’s book, This is What Inequality Looks Like.

Conversations about race aside, Idaffi notes that by highlighting how ‘successful’ candidates have climbed and overcome many hardships, the PAP “drills in our minds that the state has created fantastic systems where social mobility is uninhibited”.

He also points out that this sort of framing, in which living with twelve people/father working as a taxi driver/etc. are labelled as hardships, also acknowledges that they are “bad”.

With all the talk about how PAP candidates always come from some humble background that we learn about during their press conferences—something that might make them sound more electable, perhaps—it’s no wonder that people have started to break down our narratives of meritocracy and success.

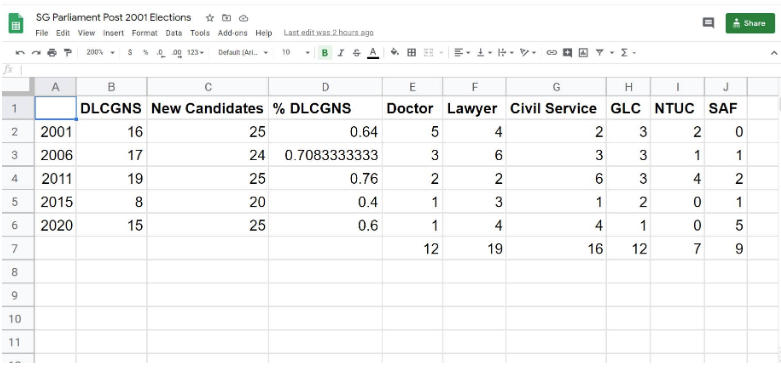

Speaking of humble backgrounds, apparently some people lament that there’s no diversity in PAP candidates. This problem nagged at Chang Zi Qian, who eventually used his “itchy kay poh fingers” to do some research and posted his findings on Facebook.

Zi Qian went through almost 20 years of data, tracing the backgrounds of PAP’s new candidates from 2001 to 2020.

This strategy has not changed for GE 2020. About 60% of the candidates for this election are also DLCGNS. What has changed is the remaining 40%, in which there are now more polytechnic graduates and fewer candidates with MNC backgrounds.

In general, recruiting from DLCGNS backgrounds aligns with the government’s image of being “methodical, technocratic, data driven, logical, and their perceived lack of emotions”, as people with these backgrounds tend to be more “thinking” or “left-brained”. There is also a distinct lack of representation from the liberal arts and creative sectors.

The wealth of online commentary shows us that this is a digital election not just for political parties, but for voters as well. Candidates forced to be more active on social media further amplifies this, giving the electorate more material than ever to analyse and pick apart.

Younger Singaporeans in particular have taken it upon themselves to spearhead the bulk of this content creation. Whether it’s dissecting Ivan Lim’s overwhelming popularity through line graphs or breaking down the ideologies behind our narratives of success, they are pulling together information in a bid to be more informed.

Relying on national broadcasts and print newspapers might be a mainstay for some, but younger voters are leaving these mediums behind in favour of doing their own research.

This General Election, it’s become clear that you don’t need to be part of the media to have your voice heard. As we’ve seen, many of those delivering critical and insightful commentary are ordinary Singaporeans with 3 things: access to technology, the patience to do research, and a simple desire to say something.

Have a lead for a GE 2020 related story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.