While I will not celebrate the murder, there are situations when it is understandable.

To get the caveats out of the way, I’m obviously not talking about the legality of murder, so we can leave out legal justifications like self-defense. I’m also not talking about “killing” people, which can include things like euthanasia, hitting someone with a car by accident, military combatants etc.

I’m referring to pre-meditated murder with malice aforethought. And in the court of public opinion, it is not just possible, but human to empathise in certain situations.

—

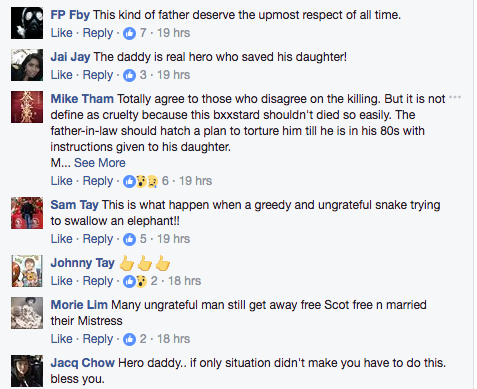

As the Boon Tat Street Murder unfolded, we pieced together a narrative that held an uncomfortable truth. That despite being a murder in broad daylight in the CBD (an unusually brazen crime, especially for Singapore standards), we could still relate to what the accused was going through.

For many, it’s not impossible to imagine being in a situation one day where our son-in-law might cheat on our daughter. Neither is it impossible for us to imagine having to one-day deal with an impending divorce and a messy division of family assets.

A situation like this would give most of us some level of emotional turmoil, and this is where we find that we are able to relate. If we are to believe what has been reported in the news, we might then perceive the accused as a man trying to protect his daughter and his family, and not as a cold blooded killer.

While this does not absolve the accused of guilt, it does make him less morally culpable in the eyes of some people. Are they wrong to feel this way?

For example, if the victim had raped the accused’s daughter, would we then feel that the accused is even less morally culpable? Or if the victim had been abusive? Would we have felt any different?

Underpinning all of this is the fact that we are guided by different value systems. For example, while adultery might be a deadly sin to some, others might not feel the same way. Given the divorce rates, some might even accept it as a normal part of modern relationships.

The fact is, we are our own moral authority. A legal system can provide guidelines on what is socially acceptable behaviour, but ultimately, only we get to decide what is right or wrong. We decide what value system suits us best, and we then align our lifestyles accordingly.

For some people, religion is the moral authority. Others live by a simpler code based on mutual respect.

Not all of us subscribe to the saying that “two wrongs don’t make a right”.

So the takeaways from this incident are twofold: first, society will continue to empathise with murderers as they see fit, and they are not wrong to do so. Who we choose to feel for is decided by a subjective mix of influences that cannot be judged in black and white. And second, be thankful that we no longer have a jury system.