The accounts of the latter alone are worth the entry fee of the book. Different jobs, as we know, can differ so vastly in culture and vocabularies used that they seem almost alien to one another. Have a copywriter tell a banker to ‘ideate’ or, in this case, a drag queen ask a pet crematorium worker to ‘tuck’, and only blank stares will ensue. Hard at Work bridges this gap and lets anyone as kaypoh as I am satisfy their curiosity about other jobs. (For the inquisitive, when a drag queen ‘tucks’, she is pushing her genitals up her … you get the idea.)

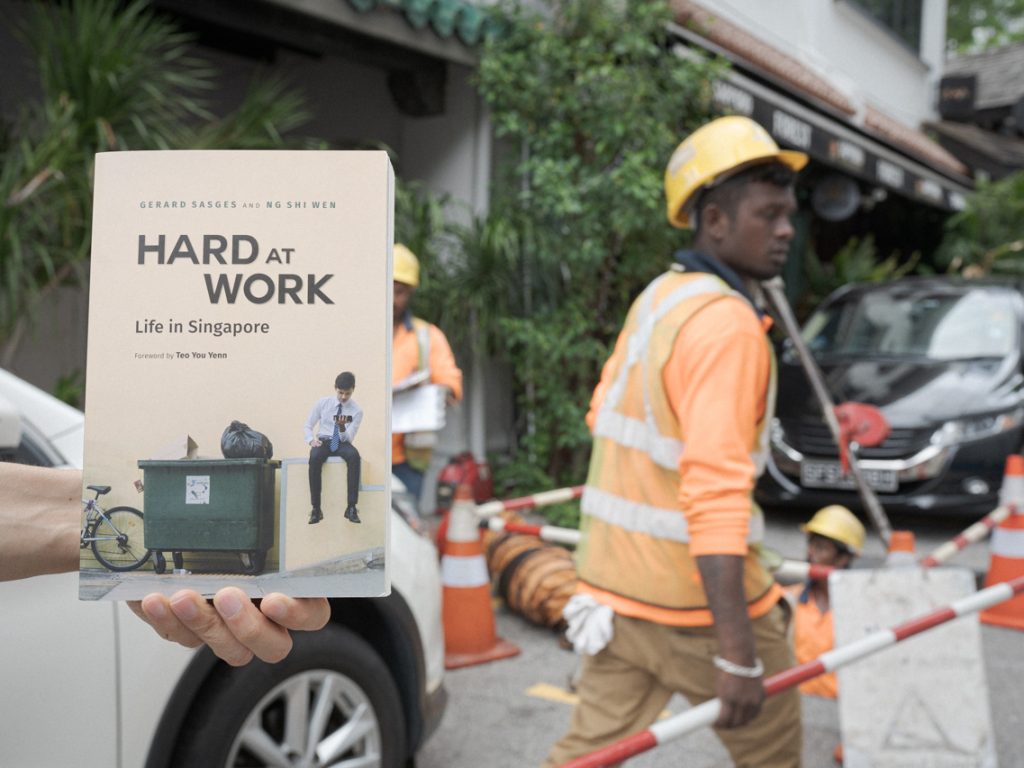

For one, the bulk of the interviews are derived from people in industries like “selling”, “making and repairing”, and “recycling and cleaning”; in other words, industries that typically comprise low-wage and low-skill workers. We read about the elderly karang guni man who earns “at most $200” in an entire month; the electronics worker who “work close to 10 years already, pay … only $1000 plus”; the student care teacher whose “salary is only $1.5K” despite being in a more ‘respectable’ profession. This is juxtaposed against the accounts of the doctor, still in his 20s, who earns $5000 to $6000 a month, or the $6000 in commission the real estate agent made when he closed his very first sale at 22.

The book is not pitting profession against profession, or salary against salary. It is not suggesting that it is inequitable for a real estate agent or doctor to earn so much while a karang guni man earns only $200 a month. To put a hard, numerical value on the utility of a profession is something best left to economists, and even then, it’s a vague practice that is hardly a science at all. After all, how can you conclude that saving a life is worth $5000 a month, while “collect[ing] rubbish one lor” only $200?

Here [in the electronics factory] work close to 10 years already, pay not good lah, work so long already only $1,000 plus eh, no good lah! But this job I like lah, want to 60 years old already still can work … Also not so stress, still got tea break 15 minutes, if don’t go for tea break can take longer lunch, 1 hour not 45 minutes. … Got job okay already, people like us low education, as long as willing to work, got job, straightaway grab already, just work lor.

That is to say, what we have today is built on what they don’t.

I used to be a cynic who dismissed the Merdeka Generation Package as another shameless scheme instituted by the government to buy votes. But having read the 60-year-old electronic factory worker’s tale of leaving school to join the workforce at age 13, I am reminded of this particular advertisement, in which—stop me if you’ve heard this—a girl has to forego further education so that she can work in a factory to support her family.

In the words of the electronics factory worker:

Primary 6 study finish, come out and work already loh! … Last time I want to study night class one, my mother don’t let lor, boh bian [no choice].

If our famously welfare-averse government has deigned to implement such a measure, surely there are other policies, nowhere as far-reaching or painful on the purse, that it can implement?

There are already “Progressive Wage Models” (read: a euphemism for minimum wage systems) in place for the cleaning, security, and landscape sectors. That’s a good start. But, as Hard at Work demonstrates, there’s still a long way ahead for us to go.

Are we doing our jobs properly? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co