A prostitute leans against a Portland Street doorway, her lightly crimped hair and short black dress are a throwback to the 90’s. She tells me her name is A. A says we can speak at her post, where she can still attract customers. But we must keep our eyes peeled for the police.

This job is relatively new for A, who tells me, “At first I felt ashamed, and even now after five months, I still feel it. I feel like other people who pass me on the street look at me and think I am so cheap to be doing this, that I must not have values.”

A is from the mainland, and believes that being a divorcee gives her a slight upper hand because she understands what men want better than a young woman without experience. Still, most customers only come once. There are plenty of other women to be had in the neighbourhood.

The married and divorced alike have turned to prostitution—which is legal in Hong Kong—as a way to support themselves in their costly new home.

Hong Kong historian Jason Wordie explains,“These women often have limited job skills and low education levels, and sex work makes more money than other entry level jobs. Once they come to Hong Kong on a one way permit from China, they’ve given up their residency and it can be difficult to go back, they won’t be eligible for social services.”

The permit situation is equally difficult, he adds, “On a two way permit they aren’t supposed to work, so that sets them up for breaching their terms of stay if they engage in sex work while they’re here, but there isn’t much else they can do to support themselves.”

Lee, a five year veteran volunteer at Zi Teng, a non-profit dedicated to improving the rights of sex workers in Hong Kong, says that sex workers earning income without a visa are at an increased risk of theft and abuse despite an improving relationship between prostitutes and law enforcement.

In the days preceding the 20th Anniversary handover, Lee says a number of women with whom Zi Teng does outreach work reported that the police warned them to stay off the streets to avoid strict enforcement of non-solicitation laws. She suspects that this was meant “to keep the society ‘clean’ in the eyes of the officials coming from China.”

“Some of the police actually went around advising women that they should take a ‘holiday’ while Xi Jinping was in town.”

The women reporting these interactions heeded the advice.

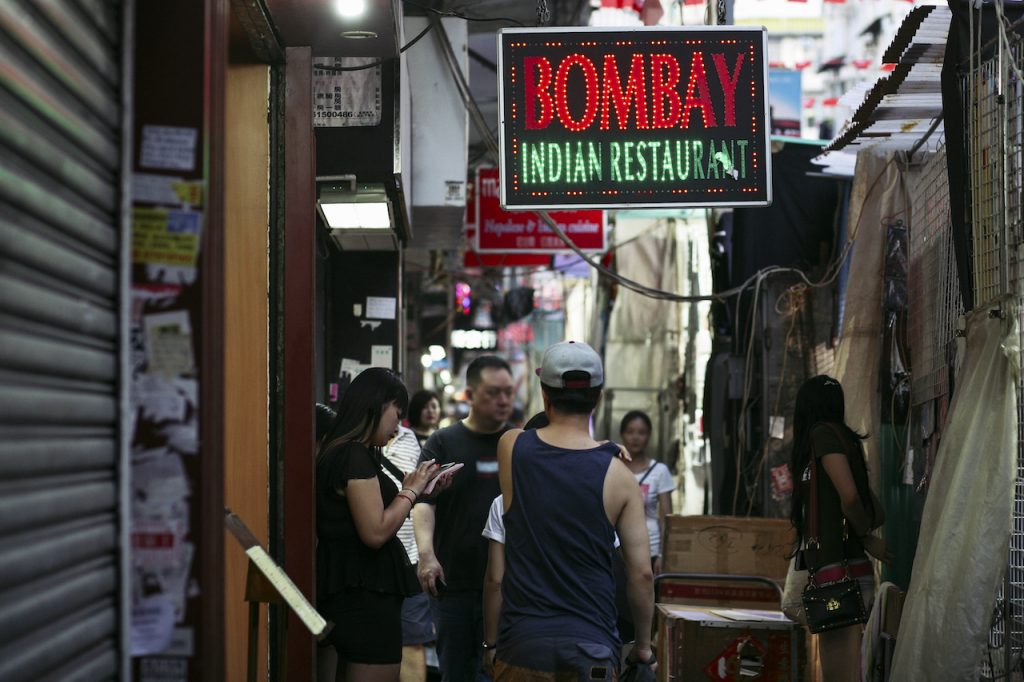

Apart from the days surrounding Xi Jinping’s visit, sex work is normally visible in specific Hong Kong neighbourhoods. In Yau Ma Tei, surrounding the bustling night markets, bored looking women in skintight dresses and high heels dot the make-shift alleys, covert behind the brightly lit tents of Temple Street Market.

The more daring women assume their positions before the shopkeepers do, selling sex before any electrical gadgets or fidget spinners exchange hands. Glancing up from their smartphones to assess possible clients, they vanish into doorways when the police sweep through.

She lives in another part of town with her ten year-old son, and her work here is exclusively to pay for their living expenses. Her ex-husband moved back to mainland China; free from the clutches of Hong Kong child support laws, he left Alice to take care of their son on her own. He now lives with a younger woman whom he supports.

Alice says she feels relatively safe because she technically works for a “foot massage” place upstairs that employs a handful of women. The only harassment she’s received has been from the police—a plainclothes officer once arrested her for “solicitation” as a result of her visual presence from the street and her immediate flirtatiousness.

“I had to go to the court in Kowloon City and pay a fine, I think it was around 1,000 HKD,” she says, “I try to be more careful of that now.”

One of the not so glamorous benefits of being a divorcée, says Alice, is that she is not worried about having a family someday. She is only concerned with supporting the family she already has.

“At the beginning I felt very embarrassed, and I still feel do sometimes, but life has to go on. I’ve gotten used to it,” she shares.

Down the remainder of the street, a number of women stand in doorways together in twos and threes wearing matching black and white, some with massage menus in hand. These women will not speak to me—“I cannot, my boss …” is the de-facto Mandarin phrase used.

Each woman my translator and I speak to on the street communicates in Mandarin rather than Cantonese, Hong Kong’s primary tongue. Using miss148.com, a mainland-run site that profiles Hong Kong sex workers by location, we called over a dozen women whose profiles listed them as Cantonese speakers. Without fail, the voice on the other end of the line responded in Mandarin, unable to converse in Cantonese.

She is also a divorcée. With no children to care for, Candy supports her elderly parents as much as she can, but it’s getting harder she tells me.

“It has been very unstable. Sometimes I don’t have any customers for the whole day and then I have nothing to eat. A week ago I only made $800 hkd in three days,” which is around four clients, judging by her prices, “This area is very competitive.”

With neither full citizenship nor a career to return to in Mainland China, Candy feels that she has no better option, “There is nothing to like about this job and nothing to not like, it is just a job, that is how I see it.”

Zi Teng says it can be exceedingly difficult for mainland Chinese women who move to Hong Kong to be with their husbands to find employment in Hong Kong. One woman who came to Zi Teng for testing previously worked as an engineer in China. In Hong Kong, neither her degree nor her experience was recognised.

Unable to find a position with suitable pay, she is now divorced, living in Hong Kong, supporting herself and her son through sex work.

“If she were to go back to China she would have no access to government services, and she would have to endure the shame of returning home as a divorced woman,” says Lee.

“In China, that shame is directed at the family, not just the individual.”

Lee suspects that the commonality of these words is indicative of a broader perspective.

“I do not think they are very analytical about it. If I were to ask many of these women how they feel about what they do I do not think they would respond very emotionally. To them it is just what they need to do, it is a job. But, if I were to ask them if they could go back, would they choose this again, I think the answer would be ‘no’.”