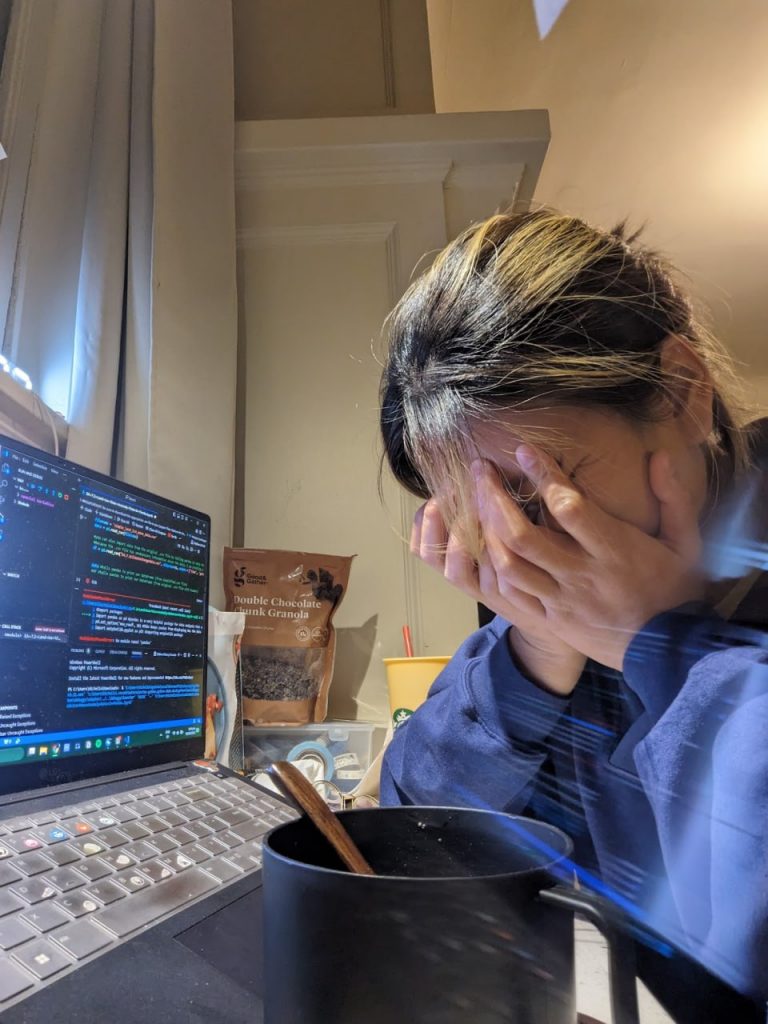

Top image: Courtesy of Michelia Teh

In a speech at the University of Singapore in 1966, Lee Kuan Yew opined on the role of a university: “It is first, to produce the teachers, the administrators, the men to fill the professions—your accountants, your architects, your lawyers, your technocrats, just the people to do jobs in a modern civilised community.

“And next, and even more important, it is to lead thinking—informed thinking—into the problems which the nation faces.”

His words were spoken in very different times—Singapore has come a long way since its early independence years. But the first objective he mentioned seems to have endured over the years. I’d even go as far as to say it’s shaped how generations of Singaporeans think about university. (The second objective, however, seems to have fallen by the wayside.)

Most of us grow up hearing that we should enrol in university because it’s a stepping stone to a ‘good job’. For a few decades, this was true. As a millennial, I saw the university graduates of my parents’ generation enjoy the spoils of their ‘good jobs’, successfully raising kids and buying property with their salaries. They stayed in the same companies for decades before retiring with healthy nest eggs.

Now, however, this social contract is breaking down. Recent graduates say they’re struggling to find jobs due to fierce competition. University students, desperate to differentiate themselves, are turning to ‘internmaxxing’. In today’s cutthroat job market, a university degree doesn’t protect you from layoffs, nor does it mean your job is safe from being stolen by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Amid an uncertain job market and growing disillusionment towards the institution of higher education, there are some Singaporeans who are making a radical choice. In the name of self-development and learning, they’re opting for a relatively unknown school that promises an “immersive global education”: Minerva University.

Not Like Other Universities

If you search for ‘Minerva University’ on Reddit, chances are, you’ll stumble upon threads asking if it’s a scam. Some also speculate that their low acceptance rate—about 3 percent—is “artificially lowered”.

Minerva is pretty much the antithesis of your conventional university—at least, the typical university that Singaporean students go for.

You won’t find the private university on the QS World University Rankings. Instead of traditional lectures, all instruction takes place through online seminars of about 20 students. There are no exams and no bell curves. Instead, students are assessed through assignments that test how well they apply concepts. The university has no central campus; students study in a different city each year. Historically, different cohorts have spent time in different cities, including San Francisco, Berlin, Tokyo, Seoul, Hyderabad, Taipei, London, and Buenos Aires. First-year students learn general skills like critical thinking and problem-solving before choosing their specialisations in their second year.

As universities go, Minerva is also relatively new. The school was founded in 2012 by American Ben Nelson and is rooted in his three-decade-long effort to push for university reform in the US. When it became clear to him that traditional institutions weren’t willing to change, he decided to create a new one from scratch. Minerva’s inaugural class of 103 students graduated in 2019.

Michelia Teh, 22, a second-year Minerva student, assures me that her school is very real. We’re speaking over a video call because this school year, she’s studying in Buenos Aires.

She’s currently the only Singaporean in her cohort of about 200. Apparently, Minerva University is so unknown among Singaporeans that she’s had to perfect a ‘sales pitch’ whenever she meets new people.

“I always start with ‘We go to a different country every year’ because that’s how you get people’s attention,” she laughs sheepishly. “I’ve been working on making my pitch shorter, but I always feel that if I don’t explain the whole thing, then I’m giving a false picture.”

Joshua Yue, a 2021 graduate who majored in Strategic Finance and Economics, tells me that his parents were understandably sceptical about Minerva when he told them he wanted to transfer there from Singapore Management University (SMU).

After all, he’d stumbled upon the university on Facebook, of all places. And back then, Minerva’s first batch hadn’t graduated yet.

The 30-year-old remembers his parents asking, “Why would you give up SMU to join this university that you found on Facebook? What is this university even about?”

Joshua says his parents raised him to follow the traditional Singaporean path: Study hard, get into a good university, and be set for life. “But essentially, I’m telling them there’s a different approach to life.”

A Leap of Faith

For those concerned with rankings and prestige, Minerva might seem like an odd choice. But for Michelia and Joshua, who both spent a year in local universities, Minerva was something fresh—something different.

Michelia says her time at the National University of Singapore (NUS) felt more like ticking boxes than actual learning.

“We have this exam culture in Singapore where every exam is like a life or death situation,” she muses. “I really didn’t feel like I was learning anything. I learned a lot of facts, but I didn’t really learn knowledge.”

Even when students spoke up in class, it felt more like they were trying to hit their class participation quota instead of actually engaging with the topic, she adds.

For Joshua, reading economics at SMU felt like the sensible, practical choice. But he gradually began to realise that he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do.

“I was asking myself, are there any other choices if you’re not trying to be a consultant or banker? What else is there?”

They both describe a similar thought process: If this were the learning experience at a top university—approved by their parents, no less—perhaps they needed a school that was a little more avant-garde.

On the other hand, Amalanand Muthukumaran, 29, a 2021 Minerva University graduate, didn’t have to suffer through the local university experience to know that he wanted something different. In fact, he’d already applied for Minerva University while he was still in his junior college years at Raffles Institution.

“One reason I picked Minerva was curiosity and adventure. The second was that I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, and the ability to select a major later on really appealed to me.”

The need-based financial aid was also a draw; Amalanand saw Minerva as his chance to experience the freedom of studying abroad without the bond that usually accompanies scholarships.

While Amalanand’s parents, like Joshua’s, needed some convincing, he says that he won them over by assuring them that his seniors at Minerva were able to secure internships with companies like Twitter (now known as X) and Uber.

For any student, the decision to leave a safe, well-trodden path is never easy. But all three maintain that they’re glad they gave Minerva a shot—and that their parents all eventually got on board.

Growth, Struggle, and New Perspectives

Many people mistake Minerva for just another online university, but that’s not quite right. While its classes are conducted virtually, the programme is far from a remote-only experience. Minerva houses students in residential halls throughout their different city rotations, and even involves them in civic projects with local organisations.

Still, the enduring stereotypes about online universities—that they’re degree mills, illegitimate, and ineffective—continue to affect some Minerva students. For example, Michelia tells me that some of her friends have been told that their school “isn’t real”.

Minerva University, however, is in fact accredited. All three Minervans—yes, that’s the demonym for Minerva students—also say they stand behind the quality of the education they received.

In fact, some of them found the transition from Singapore’s education system to Minerva’s incredibly challenging.

Michelia tells me in all honesty that she expected Minerva’s curriculum to be a walk in the park. After all, Singapore’s education system consistently ranks among the best in the world. But her first semester was probably one of the hardest times in her university career, she says.

Joshua, too, candidly admits that his grades tanked in his first semester.

“I came in with the Singapore mindset—how do I get the best grade for this assignment? I think I’ll carry that legacy with me wherever I go,” he says, laughing at himself. When he finally shifted his focus from grades to actually learning, things clicked into place.

“I thought of it this way: Let’s not focus on the grade. Let’s just focus on the metacognition aspect of learning,” says Joshua, referencing a learning process that essentially involves taking a step back from the subject at hand and reflecting instead on how you’re learning.

“I came to find enjoyment in learning, which is something I had never really experienced until joining Minerva.”

Beyond the grades, the diversity of the cohort and the global experience also broadened their perspectives and catalysed personal growth. For the first time, they found themselves surrounded by people who were just as curious about the world as they were.

“I made friends who care about a lot of different things, and are from different places. Even after college, they continue to give me inspiration and ideas,” Amalanand says.

Minerva’s globe-trotting aspect also isn’t exactly the same as your typical exchange programme—the city you’re in becomes your campus. This means that students are encouraged to base their projects on the city they’re currently living in.

Michelia recalls that for one ethics module, she was based in San Francisco. One of her assignments was to interview anyone in the city about their ethical views. With a local church’s permission, Michelia interviewed one of their staff members about their views on abortion. That assignment left her with a better understanding of ethical frameworks than any test or reading could.

“I find myself thinking about the things that I learned in school almost every day,” she reflects.

Trade-offs and Realities

Choosing Minerva is not without its downsides. In Singapore, at least, the ‘branding’ of one’s university still counts for something. For example, there’s still a prevalent stigma against graduates of local private universities. It isn’t hard to imagine some employers being reticent about hiring a graduate from a school as little-known as Minerva.

“A very practical downside is that employers don’t know who we are,” says Michelia. “I think that many doors would definitely have closed for me because I didn’t stay in NUS. But I also think that I’m almost happy that those doors closed for me.”

But perhaps she needn’t fret too much. Joshua and Amalanand are both gainfully employed; the former works in fintech and the latter works in an educational technology startup in San Francisco.

Amalanand, for one, says he wasn’t anxious about job hunting in Singapore because casting his net internationally felt like the most natural thing to him. His global university experience—he got to intern and build connections in South Korea and the US—definitely nurtured that outlook.

It’s easy to say students should choose a university or course based on passion or personal growth. In reality, most worry about jobs. Understandably, many treat university less as an intellectual pursuit than as a hedge against unemployment. But this calculation is increasingly unstable.

If you make decisions based on the imagined demands of some future employer, you’re chasing a moving target. Instead of trying to guess what the market will want years down the line, a more solid bet is cultivating your own capabilities and curiosities. Those are the things that’ll stay with you longer than any employer ever will.