‘After the Vote‘ is a RICE Media series where Singaporeans from all walks of life share their hopes for Singapore—the changes they envision, the values they want to uphold, and the future they want to help shape.

After GE2025, we take a step back to explore the bigger picture: What kind of Singapore are we building beyond this election?

All images by Kimberly Lim for RICE Media unless otherwise stated.

In 1972, six opposition parties came together to sign a memorandum to then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, asking for nine changes to be made to Singapore’s electoral system.

Their demands weren’t too different from the changes the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) is pushing for now, says Dr Elvin Ong, Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

“They asked for an independent election commission. They asked for 30 days of electoral campaigning.”

Dr Ong paraphrases the response from the government of the day: “Cannot lor.”

And that was that. 53 years on, SDP has taken up the mantle of pushing for electoral reform.

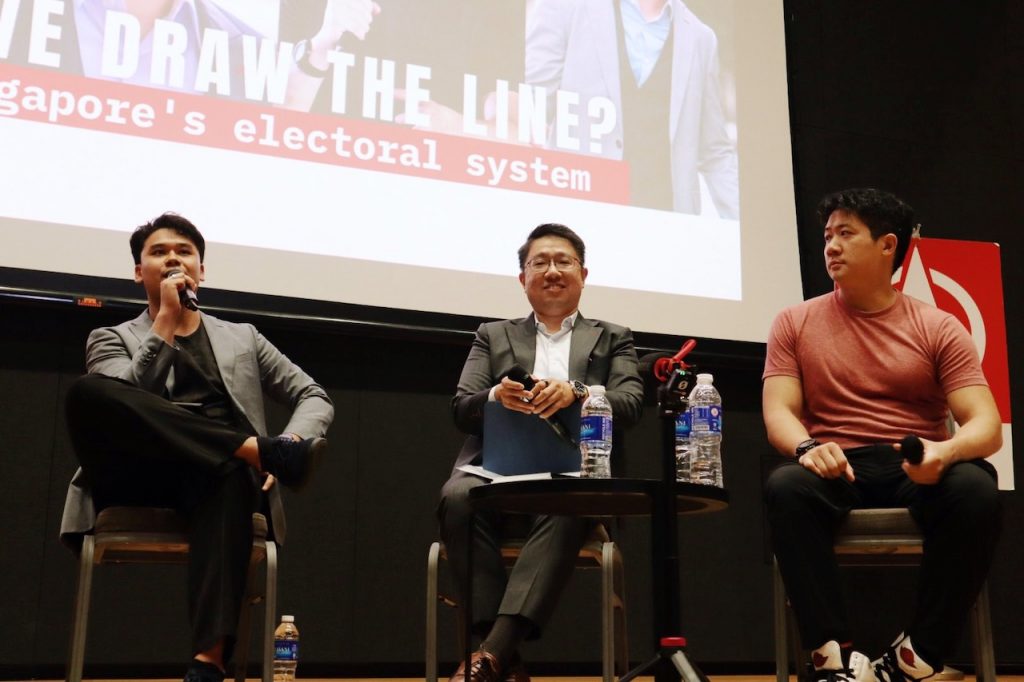

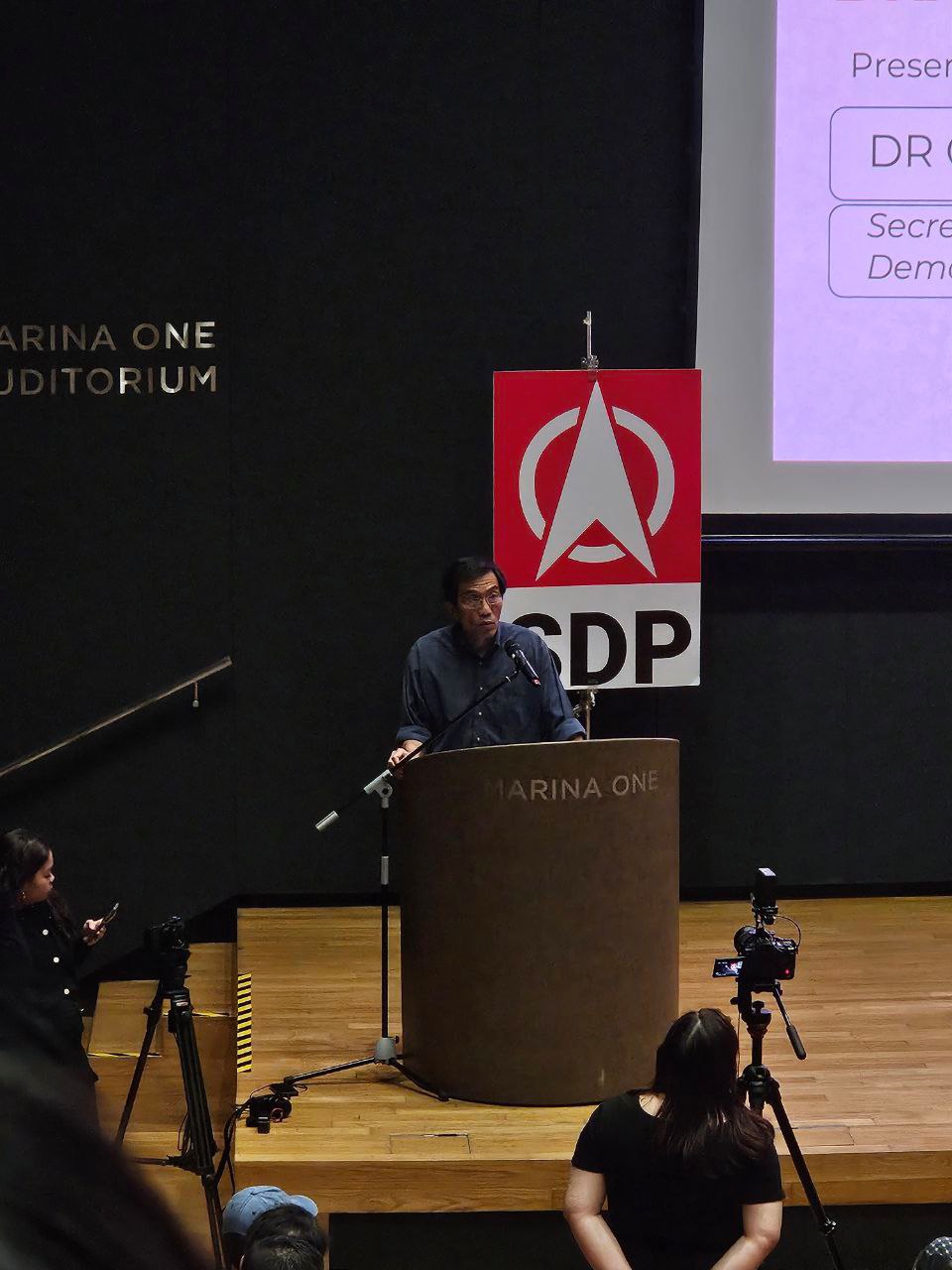

That’s how a 340-strong crowd ended up packed into an auditorium on August 23 for SDP’s public forum titled ‘Where Do We Draw the Line?: Reimagining Singapore’s Electoral System‘.

Singapore may have gone decades without meaningful electoral reform. But the fact that hundreds of members of the public still wanted to spend a Saturday afternoon learning about the topic speaks volumes about our appetite for civic engagement today.

Reform: An Uphill Battle

SDP’s reform project is part of the party’s Renew, Rebuild, Reignite: Roadmap 2030 campaign leading up to 2030, presumably when the next general election will be held.

But the project isn’t just an opposition party effort. At least, the panel at Where Do We Draw the Line? was a non-partisan one—consisting of Dr Ong, mathematical and theoretical physicist Jo Teo (no relation to the MP), former Workers’ Party MP Leon Perera, and GE2025’s star independent candidate Jeremy Tan (aka Encik Bitcoin).

SDP’s Dr James Gomez opened the event by calling for six changes:

1) An Elections Department (ELD) that’s independent of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO)

2) A reformed Electoral Boundaries Review Committee (EBRC)

3) An end to the Group Representation Constituency (GRC) system

4) A minimum campaign period of 21 days

5) More time between the release of electoral boundaries and the dissolution of Parliament

6) A review of the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (NPPA) to ensure fairer media coverage

If these sound familiar, it’s probably because opposition parties and academics alike have been pushing for these changes for years. There have been numerous papers and public engagement sessions calling for the same few changes. Naturally, these themes also came up when the Leader of the Opposition Pritam Singh made his maiden local podcast appearance on YahLahBut recently.

That’s probably why the ensuing forum discussion didn’t bother rehashing the six changes above. Instead, the event felt more focused on a different question: How do we actually move the needle?

Dr Ong offers a realistic view: ”Any successful type of electoral reform is going to be very, very, very, very, incredibly difficult.”

Electoral reform is an institutional change. You’ve got to pass laws to make it happen. This means convincing the ruling PAP (who were elected under this very voting system) that changing it will be in their favour.

The other big obstacle is getting the public on board.

“Based on my review of the publicly available survey data out there, most Singaporeans are pretty happy with our electoral system, even though there may be grudges here and there,” Dr Ong says.

“If the mass population has these opinions, how are you going to convince people that there’s something really wrong and that you should put in effort to understand, to try to change it? That’s a difficult task.”

Change, One TikTok at a Time

Indeed, without people like Jo, who made waves for their TikToks analysing the math behind the GE2025 electoral boundaries, inequities in the system may have remained invisible and unchallenged.

(For a detailed explanation on how someone living in Bukit Panjang has less voting power than someone in Kebun Baru, you can take a gander at this illuminating analysis Jo published on RICE in May.)

Otherwise, here’s my attempt at explaining it: Your vote ‘weighs’ differently depending on where you live. Despite EBRC keeping the average elector-to-MP ratio roughly around 28,000 each year, the actual range deviates widely among constituencies.

In Bukit Panjang SMC, you’ve got one MP taking care of 33,000 voters. In Kebun Baru, the ratio is 22,000 voters to one MP.

If Jo hadn’t started making TikTok videos breaking down these stats, terms like ‘voter-to-MP ratio’ and ‘malapportionment’ would still be Greek to me (and probably many other voters).

YL, a university student I spoke to after the event, tells me that she’s grateful that people like Jo aren’t gatekeeping knowledge. Instead, they’re making use of social media to make things palatable and digestible for the layperson.

”The person who really drew me to come to this was Jo Teo,” says YL, who only turned 21 after GE2025. The self-confessed heavy TikTok user came across Jo’s videos and found them engaging even though she didn’t get to vote in this election.

“I’m not a math person, but I think empirical data is really important because we can really call out discrepancies through numbers.”

Perhaps this is why it’s crucial for any reform movement to rally voices from outside the political sphere.

We’re all used to opposition politicians demanding change. As Leon says, the typical response he gets when he tries to educate the public on topics like electoral reform and the secrecy of one’s ballot is “Of course you would say that.”

But when you hear from an academic who champions electoral reform based on hard math, it’s hard to argue with the numbers.

It also helps that these days, anyone with a TikTok account—honestly, who doesn’t have one?—can watch people like Jo and Jeremy breaking down political content in a way that speaks to the masses.

For example, Jeremy shared with the crowd that he’d intended to post an infographic of how well he’d polled at each polling station in Mountbatten SMC.

Unfortunately, right after he posted the graphic, several lawyer friends cautioned him that he might be violating the Parliamentary Elections Act. He has yet to receive a reply from ELD on whether he can post his infographic, but he’s promised to share the information if he ever gets the okay.

Information on how each polling district votes typically hasn’t been made public by candidates in previous elections. But Jeremy says he wants to do things differently: “I think it’s very important that if anybody has information, you should just share it.”

The topic of electoral reform is no longer one that the elite, well-heeled, politically aware crowd chat about at their meetings. It’s more accessible now.

In Singapore, where political apathy has been breeding over the years, any sort of increase in political literacy and engagement is worth celebrating. Political literacy among the masses is integral for any healthy democracy, after all.

Starting ’Em Young

Still, social media is no silver bullet. Leon, who was part of the most recent electoral reform effort by human rights organisation Maruah a decade ago, is well aware of that.

“It really has to be one conversation at a time, one person at a time,” he offers.

“And that effort really has to take place among the broad mass of people—not just political participants and activists and civil society groups, but even ordinary people who feel a certain way and can be bothered to speak out a little bit.”

While events like this public forum are encouraging, a perennial limitation is that it’s typically the same faces attending these events. That is, according to an attendee who wishes to remain anonymous.

The 44-year-old, who works in arts advocacy, attended the public forum with his wife and his 4-year-old daughter.

“We need more spaces, and everybody does have to work very hard to attract a lot more people to these events,” he affirms.

“You want young families and your sandwich generation—I think they actually have a lot to say. Perhaps more regular and more kid-friendly events would help.”

His daughter has been tagging along to various arts and politics events, he says. Already, she recognises the logos of each political party. She’s even starting to ask questions about politics.

”I’ll even answer her questions on things like ‘Why do we vote for our government?’ I tell her that we are voting to decide who takes care of Singapore.”

It’s never too early to get our future voters well acquainted with politics, I guess. But this is also a reminder that political discussions don’t have to be daunting. There’s space for everyone to participate regardless of age or education level.

Do We Really Need Reform?

In the wake of the recent SG60 fanfare, I’ve come to realise that patriotism means different things to different people. For some, it means remembering our founding fathers. For others, it’s making sure their national flag is flying in the right orientation.

But for the 340 people in attendance, it’s daring to ask if Singapore can do better and be fairer, even as the odds seem stacked against electoral reform.

While a majority of the country may feel that our elections are fair, it’s events like this that invite us to examine what ‘fairness’ means.

Is it deemed fair, for example, that our campaign period is so compressed that we barely have time to get properly acquainted with new candidates before voting? Or that EBRC’s process of redrawing electoral boundaries remains largely opaque?

To borrow the words from Dr Chee Soon Juan’s closing speech: “Singapore needs more than just parades, patriotic songs, and grandiose national day rallies. It needs soul. It needs belongingness. It needs compassion. It needs freedom. It needs reform.”

If we truly want to build a better future together, we don’t necessarily need to all be on the same page about electoral reform—even the forum panellists had differing views at some points.

But we need to be willing to seriously consider and debate it out loud. What we can’t afford is to dismiss the idea of reform altogether, simply because the comfort of the status quo feels easier.