This post was first published Apr 9 2019.

For seventy years, the Gurkha Contingent has been Singapore’s elite guard and counter-terrorism force. To ensure their neutrality, they live in their own compound in Mount Vernon Camp, which caters to their housing, necessities, and recreation.

In Singapore, many of us view Gurkhas not as permanent migrants, but as foreign contractors—albeit ones whom we accord much respect and admiration. The key difference, however, is that contractors tend only to see their families on video calls; Gurkha children are born and raised in Singapore, with the full knowledge that they will one day be repatriated from the country they grew up in.

There are no schools in Mount Vernon camp. The small Gurkha community may live in relative seclusion, but their kids are educated alongside the rest of Singapore, and are just as foreign to the country as I am—that is to say, not at all. Their passports, however, will always be a reminder of their marked difference, emblazoned not with a lion and tiger, but the mountains of their true home.

So what is it like growing up as the child of a Gurkha?

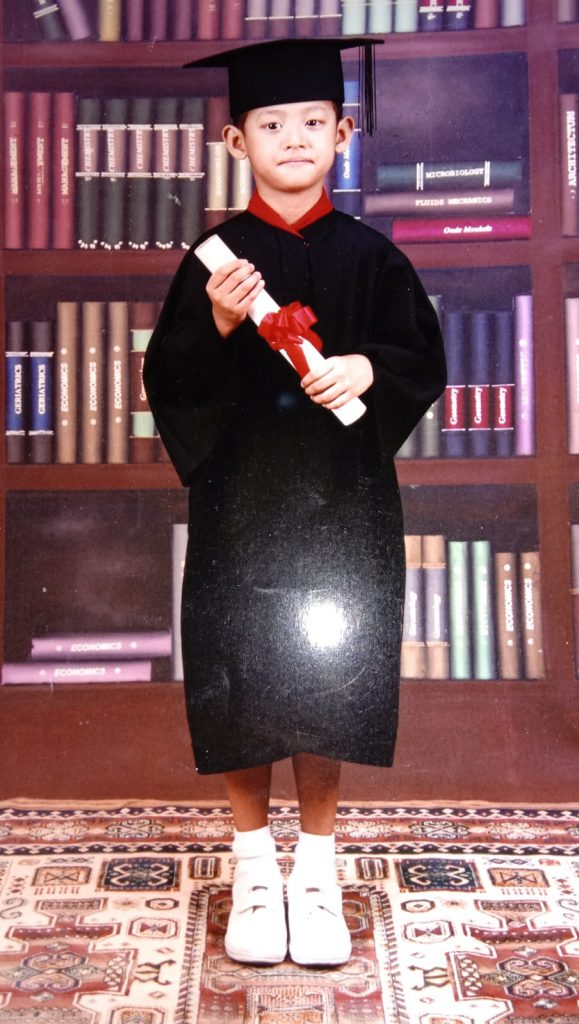

Namsang Limbu, 19, doesn’t feel any different from the average Singaporean. Most Gurkha families are in Singapore on a dependant pass; Namsang’s father, however, retired from the Gurkha Contingent several years ago. Namsang has been allowed to stay in Singapore on a student visa while he completes his studies in Republic Polytechnic. He resides in Mount Vernon Camp with his relatives, who are also a Gurkha family.

Over the years, I’ve heard rumours floating around that Nepali students in Singapore face racist remarks and treatment in schools, but never witnessed any for myself; perhaps because Nepali students are so concentrated in schools near Mount Vernon.

And so I ask Namsang if he’s experienced any racism.

“Obviously I do,” says Namsang, “not really direct[ly], but we face indirect discrimination.”

I ask him whether he remembers any specific incidents.

“I really have no idea,” he says, shifting uncomfortably in his chair, “It has been a while. We didn’t really get discrimination from teachers, but the students… We are, you know, immigrants here.”

“They will just joke around and say: ‘go back to your country!’ Y’know, I don’t take it to heart, just joking. It’s cool between us, but I will stand up for myself.”

Questioningly, I punch my fist into my palm, while raising an eyebrow.

“No, no—well, sometimes, when it gets serious—but not really.”

20-year-old Idha, another Nepali student, and Namsang’s former schoolmate, had a slightly different experience.

“My school was run by a bunch of racists who enjoyed picking on us because our parents are pretty docile,” she says.

Idha admits that many of her memories are of herself personally getting into trouble with school authorities. However, she recalls some incidents and policies that involved many Nepali students.

“The school is quite near to our camp; somehow all the people, teachers, higher-ups, used to think that we all lived in the same area: the two blocks that they could see.”

Because of this, Nepali students had no excuse to be late for school, the administration reckoned. In actual fact, however, Mount Vernon Camp is fairly large, stretching from the school all the way to Joo Seng, and is set to expand further.

After several incidents of tardiness, the Nepali students were given a particular timing to report to school at; earlier than the rest of their schoolmates. A Singaporean student coming at 7:45 AM would be considered on time; a Nepali student doing the same was a ‘latecomer’.

“The funny thing is,” Idha says, “There were [Singaporean] kids who lived right opposite from the school, in the terraced houses, and they would be strolling in while we were getting scolded. It was bizarre.”

On a particular day, Idha recalls, it rained so heavily that Mount Vernon Camp flooded. Because of this, they had to take an alternate route through the camp, so all the Nepali students were later than usual. Once the rain stopped, they asked the students to line up outside the school in two rows.

“Our discipline master threw a fit… He was shouting ‘I’m not going to let you into the school until you call your parents down!’ There was no reason to do this kind of thing.”

Also, Idha notes, the Nepali children were often singled out during assembly and asked to stay back. They would then be lectured.

Idha explains that her experiences differ from Namsang’s because of a change in school administrative staff (she is one year his senior). Also, Namsang was an Express student, while Idha was in the Normal (Academic) stream, which affected teachers’ perception and treatment of the students.

But this was half a decade ago, and at one school. Ditya, who is currently a student at a different secondary school, hasn’t been through anything of the sort.

“Once, though,” she says, “I heard someone say, “Go back to your country.”

“It was a teacher, who directed it to one of my classmates.”

“Most of the staff,” Idha explains, “Had bad impressions of us. As long as we’re Nepali, we’re trouble. Everyone knew that we were second-class citizens.”

Now that he’s graduated from secondary school, Namsang picks up odd jobs in his spare time. While he doesn’t have a work permit, he does freelance work in his field of study: sound engineering. Under the assumption that a Nepali education would be considered inferior to a Singaporean one, I ask Namsang why he chose to pursue his studies here, instead of back home.

“Back home, A Levels and Uni … it’s quite recognised worldwide, because it’s from Cambridge,” Namsang corrects me, “But I wanted to pursue sound and media. Back in Nepal… [it exists], but they don’t really cater education-wise.”

Once Namsang completes his diploma, he plans on furthering his studies in Canada.

“That’s the path that most [Gurkha kids] take, they will branch out … usually [to] Australia. It’s a popular country.”

Australia is the location of choice for many Nepali students. Ditya (not her real name), who is 15, also plans on furthering her studies in Australia. In school, Ditya sometimes feels pressure to perform because her father is in the Gurkha contingent:

“Sometimes I feel like I’m being watched, and I can’t do [whatever] I want, without bringing my father’s name down. So I always have to show only the side that others want to see.”

Show, as in, to the rest of Singapore?

“No, to the people who live where I live. At Mount Vernon.”

Namsang, too, feels pressured by his family history.

“Our Dads came from nothing,” says Namsang, “[Going] from a third world country to a first world country, that’s a pretty big thing. My Dad and Mom really emphasise on education, so there is an extent of pressure to do well in my studies.”

Idha, too, feels pressured by her father’s occupation, but for different reasons.

“It’s not an easy job for him… I know he’s keeping it together for my family. He earns around two thousand-ish? No one else in the family is earning, so it can be quite a challenge.” On dependant passes, a Gurkha’s family members are not allowed to take up jobs in Singapore.

At home, their fathers are not allowed to talk about work.

“He’s not a very verbal man,” Idha shares, “I don’t have very good early memories with [him]. But I know he always has the best interests at heart for us.”

Every three years, Gurkha families are allowed to take a trip to Nepal for a period of several weeks. During these holidays, they will visit and stay with their parents’ relatives. Undoubtedly, they feel somewhat different from other Nepali citizens.

“I think, living in Singapore, the mindset we have is completely different,” says Namsang, “Back at home, people don’t really have a sense of what the outside world looks like.”

Namsang goes on to explain that people in Nepal are self-centred, unmindful, and prioritise themselves; in contrast, he feels that Singaporeans have developed greater consideration for others.

“It’s a tough life there,” Namsang adds, “If a person has the same qualification, works the same type of job, they get paid so much less [in Nepal] than in Singapore.”

Ditya, however, feels there is little difference between herself and her cousins:

“My mother and her sisters grew up together … so the way they treat their children is [the same as] how we were treated. Although [me and my cousins] did not grow up together, we have a similar way of thinking.”

One would think that living in Mount Vernon Camp would make for a unique experience. It must be restrictive—even stifling—to live in an enclosed compound.

“Actually, I like it,” Namsang disagrees, “There’s a community of Nepalese, and I feel we’re comfortable living on our own.”

Ditya adds that she “feels safe and secure” to live in Mount Vernon Camp, although inconveniences crop up. Friends are never allowed to come over, and for some reason, they aren’t allowed to keep pets.

“I find it sad, because I would love to keep one,” she laughs.

Gurkha children spend their whole lives here, but they aren’t Singapore citizens. Should they be?

“Yes,” replies Namsang, and gives me a searching look, as though trying to gauge my reaction.

“I’m fine being a Nepalese citizen lah, there’s nothing wrong with it … [But] our fathers did 25 years of service here, serving this country.”

“Just like other foreigners”, concurs Idha, “It would be good if we had that option, to apply or not… I’d also like better pay for our fathers; and letting other family members work!”

Ditya, who is still a student, hasn’t really thought about any changes she might want to see in Singapore’s treatment of the Gurkha community. Namsang’s thoughts on the matter are more reserved:

“I don’t expect—it’s not really [about] expectations. Our Dads are just doing their jobs; we’re just doing ours.”

From a Nepalese standpoint, they are privileged to study and live in Singapore; from a Singaporean one, they are sometimes viewed as second-class residents, and many Nepalese children have distasteful or uncomfortable memories that testify to this fact. They are children living between two countries; two worlds that could not be more different.

A talking point of recent national discourse has been the work conditions and compensation for foreign workers in Singapore who, like any other under-represented group, are prone to exploitation. In this vein, we ought to reflect on how we treat one of our least visible and, ironically, most valuable immigrant communities—the Gurkhas.