Top image photoshopped by yours truly. All rehearsal photos provided by WILD RICE. All interview photos by Cheryl Tang.

Many of us know how getting your heart broken feels. When someone intimately intertwined with your past is no longer a part of your present, there’s this yawning wound that threatens to blister any hope of a future.

You’re not alone in this. Singapore herself has had a number of breakups.

Our most high-profile separation was with Malaysia, which saw then-PM Lee Kuan Yew shedding a single tear on national television. Less widely discussed was our brief, nonconsensual fling with Japan.

But overshadowing both has been our centuries-long courtship with domineering sugar daddy Great Britain.

We might have gained independence in 1965, but we still cling to colonialism’s vestigial legacy. Unlike our neighbours who have abrogated from Eurocentrism, Singapore has welcomed Westernisation with open arms, seamlessly internalising colonial values and the English language.

If Singapore and colonialism had a relationship status, it’d be It’s Complicated.

Alfian Sa’at cackles with glee at my extended metaphor, while Glen Goei gives me a smile that could be easily read as paternal disappointment. After all, I’m supposed to be speaking to the duo—playwright and director respectively—about Merdeka, WILD RICE’s upcoming play about Singapore’s legacy of colonialism.

But instead, here I am—as the voice of the people, a Gen Z visionary—asking them how to get over the Tinder beau who ghosted you.

Merdeka—Malay for independence—examines Singapore’s history through the interactions and conflicts between 6 characters. They are united through their disgust for the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles, and thus their traitorous little band is aptly named Raffles Must Fall.

This fictional RMF is inspired by the real-life Rhodes Must Fall. With its inception in 2015 at the University of Cape Town, the movement campaigned for the decolonisation of South Africa. Both groups struggle with the legacy of colonialism, starting with the question of why we still have venerated monuments of our colonial masters.

This is all very interesting, but I’m still waiting for advice on how to move on from my ex.

“You have to accept it, and let it go,” Glen patiently tells me, skipping straight to the end of the five stages of grief. This makes sense, because in order to start healing, we need to confront our breakup rather than hide from it.

Recognising that a relationship is truly over, and that it had reasons to be over, is the first step to moving on.

“Then, stop glorifying the relationship!” Glen hollers, before slipping right back into discussing colonialism.

“In Singapore, we clearly haven’t had a clean break. The Raffles statue still exists, and we budgeted $200 million as part of the bicentennial celebrations—the 200th anniversary of colonialism in Singapore!”

Here’s my translation of Glen’s advice into millennial speak: stop hate-stalking your ex on Instagram. Delete all your photos and texts—or at least put them away if you can’t bear to—and don’t talk or think about them as your soulmate, or the one who matters the most.

Slowly but surely, living separate lives will become natural and routine.

But colonialism is far more problematic than your average ex. With colonialism, the relationship was exploitative, even abusive. That’s what a colony is: forcefully subsuming entire indigenous populations to labour in service of an empire.

At the same time, we can’t deny that we’ve had some boons from colonialism: the English language, British rule of law. So how can we reconcile this toxic, quasi-beneficial arrangement we’ve had with our colonial masters?

This why I call Britain our sugar daddy.

“We’ve been dependent on this ex because it’s in a position of power,” Alfian tells me. Singapore’s been very receptive to Western influences, and it’s no coincidence that our country’s modernisation is intricately intertwined with our Westernisation. This might be why we’re so hesitant to denounce our colonial history.

To a certain strata of society, Singapore is seen as the poster child of ‘colonialism done right’. For example, academic Bruce Gilley cited Singapore as a success story in his paper “The Case for Colonialism”, using it to argue for the recolonisation of fragile African states.

There’s even discourse on who the ideal coloniser is. Like, aren’t we fortunate Singapore got colonised by the British instead of the Dutch?

“That’s saying I wish I had stomach rather than breast cancer,” Alfian quips. “What about no cancer?”

After all, did we really need colonialism to modernise? Alfian points to countries like Japan, Thailand, and even China, all prime examples of Asian modernities.

Sure, there have been certain Western concessions. But they’ve had the autonomy to absorb positive elements about the West without it being forced upon them.

“Part of decolonisation is refusing to be the Other,” states Alfian.

When you’re a colony you’re the periphery and the center is somewhere else—London. Your culture, your values, your possessions have all been destroyed or replaced. You inherit the good, and you inherit the bad: ideas like colonial racism; the belief in a hierarchy of difference, and that this is revealed through dividing people into races.

Even national treasures have been stolen, and the colonisers have had the gall to assert that they are in the best position to preserve these treasures. Alfian gives me the example of Javanese manuscripts that were stolen and are housed currently in the British libraries (the British have refused to return them).

Colonisation has caused a massive power imbalance, and decolonisation is all about redistributing this power—back from the West and North to the rest. It’s about being on a level playing field, to have a seat at the table as equals.

In this way, decolonisation is like any number of post-breakup rituals: to restore a new sense of normalcy, and to find one’s selfhood.

Toxic relationships and breakups are also particularly disorienting because they recolour your past. Are cherished memories now poisoned with guilt and hate? Were late night conversations and heartfelt promises all lies? How can the past look so different just because of a single incident?

This obsession with the past is what propelled Alfian to write Merdeka.

After working on Hotel—another WILD RICE play about Singapore’s history—he became interested in not just the stories of history, but how history is written.

“History is not a narrative, it’s an argument,” Alfian says, quoting historian Thum Ping Tjin. There will be different, even conflicting accounts of how the past unfolded. When we talk about history being written by the victors, it’s because powerful people can assert their side of the argument.

Colonialism was certainly the undisputed victor who got to dictate Singapore’s pre-independence history. It’s why what we’ve learnt—the whole thing with Raffles, Farquhar—centers around them and how they brought prosperity and modernity to our sleepy fishing village.

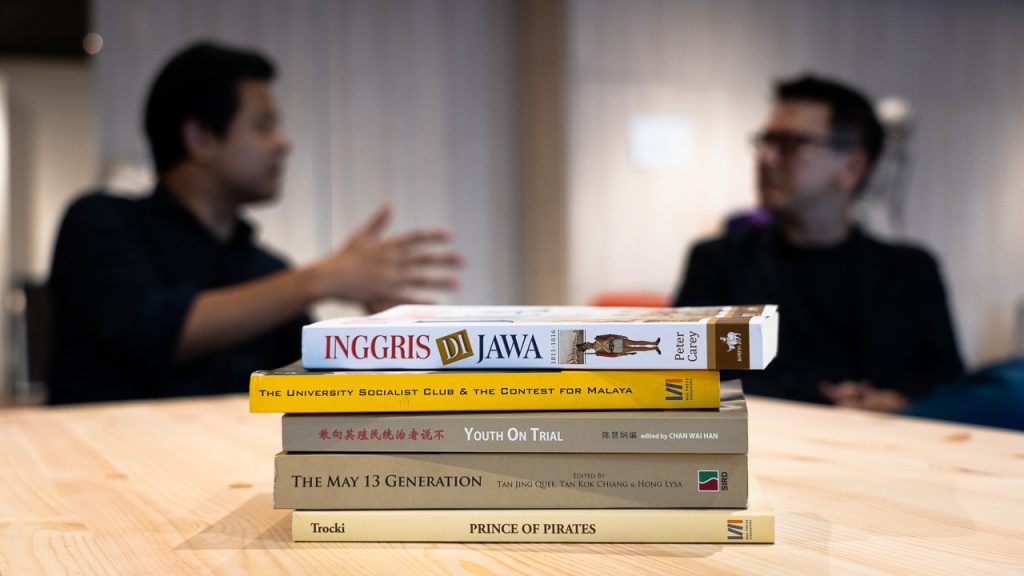

But these colonial archives are heavily biased. For one, they tend to downplay the violence committed during their conquests. Alfian shows me one example in Inggris di Jawa by historian Peter Carey, a book depicting the 1811-1816 invasion of Java.

Lo and behold, it features the rampage of Jogjakarta under the command of none other than Sir Stamford Raffles.

“Why did I not learn about this in school?” Alfian asks. Raffles was obviously a monster committing many atrocities and war crimes, but we decided than 1819 is the point zero of Singapore history. His actions before that—which make colonialism seem a lot more unpalatable and horrifying—were conveniently airbrushed out of the narrative.

“I wouldn’t say it’s propaganda,” Alfian remarks. “That’s too cynical. But these lessons also function as national building. To groom responsible and civic citizens.”

This isn’t exclusive to Singapore. It happens everywhere: in Japan, ultranationalists don’t want to mention the country’s barbaric transgressions during World War II. In Australia, narratives critical of the treatment of the Aborigines receive disapproving looks.

Nations want to push patriotic history, to have a shining beacon cast upon the country that citizens can rally behind.

But at what cost? Is a whitewashed, glorified history something everyone can rally behind, or only those who have the privilege of being in the center? What about everyone else at the margins? What history is there for them?

“There are a lot of blanks in the history we’re taught in school,” Glen says. “Merdeka touches on these blanks, and examines how they differ from what we know.”

So how would decolonisation look like in Singapore?

“We can start with the curriculum,” Alfian suggests. “Shakespeare is great, but can we look at different writers? Not just in Singapore but in the region.”

He acknowledges that steps have been taken—Haresh Sharma’s Off Centre has been offered as an O Levels text—but that more can be done.

(And if any of you smart alecs think this is only applicable to the arts and that the West is the beacon of rational, scientific disciplines, please think again.)

Unlike other previously colonised countries in Southeast Asia, Singapore has no indigenous language unique to us. With English being the de facto language, how can we decolonise a colonial language?

“Promote Singlish lah!” Alfian easily answers, a smug grin on his face.

“It’s one way of taking ownership of a colonial language, to adapt it, appropriate it, and give it value.”

Indeed, movements like the Speak Good English campaign appeal to a colonial mindset. ‘Good English’ is a very specific acrolet that serves an Anglophone elite. In reality, there are a multitude of Englishes, so why should Singlish be disqualified?

We shouldn’t be ashamed of how we speak. If foreigners cannot understand us, it’s time for them to learn Singlish.

Ultimately, Merdeka posits that decolonisation is about having multiple perspectives, about introducing alternative voices to challenge the dominant narrative of colonialism.

This plurality of opinions is important even in the realm of human interactions, because some relationships are abusive precisely because the victim is isolated and subordinate. With their abusive partner being the only point of contact, their perspectives can become skewed.

“In the end, you always need that one fried who’s like: gurrrl, you need to get out of there!” Alfian snaps, channeling every diva who’s become a queer icon.

“This guy ain’t good for you.”

“Why can’t Sang Nila Utama be our founder instead of Raffles?” Glen challenges.

“Oh you know what they say about Singaporeans being rational,” Alfian purses his lips.

The assumption that we need a historical founder rather than a mythical one is rather laughable considering our biggest tourist attraction is the Merlion (press F to pay respects).

So what if the tale of Sang Nila Utama was mythical? So what if there wasn’t really a lion?

Alfian talks about the discourse around the myth: the lion was never really meant to be zoological, but more of an apparition. Similar to legends of spotting a Garuda or Naga.

Another interpretation is that the lion is the symbol of the Buddhist throne—singhasan means throne in Hindi. Sang Nila Utama seeing a lion could mean “I saw a throne—I am king”. The actual animal could’ve been a tiger or civet, it doesn’t matter.

Listening to Alfian and Glen converse, it dawns on me that this type of decolonial praxis is not just about learning different stories. It’s also about different modes of thinking—being able to sift through the metaphorical and the literal, and understanding that there is room for awe and the unknowable when constructing knowledge.

It’s like that moment after your first—maybe second or third breakup—when you’re curled up in the fetal position, sucking calories off an ice cream spoon. You’re wondering how you could ever live without your better half, your thoughts trapped in a cycle of grief and depression.

But somehow, the realisation snaps.

I don’t need them.

And from then on, you are free.

Merdeka runs from 10-27 October at the Ngee Ann Kongsi Theatre @ WILD RICE Funan. Get your tickets here.

Relationship ended with ____, now ____ is my new bae. Fill in the blanks and complain about your terrible exes at community@ricemedia.co.