I’ll confess, few things make me confront my stunning hypocrisy more than writing passionately about climate change. Cue the hate mail.

After recent meetings at RICE where we discussed pressing issues facing Singapore, I realised this lackadaisical attitude towards climate change was a fairly common sentiment. My colleagues who profess paralysing passiveness don’t deny that the climate crisis is happening. They simply claim to have “other issues” that they’re more concerned about, such as mental health, inequality in education, or, really, their own personal and professional lives.

An experiment we did last year revealing the amount of plastic that the RICE team used even proved that we are just as wasteful as the people we berate in our socially-conscious articles.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but I don’t practise environmentally-friendly habits, at least no more than I did before I was aware of the climate crisis. For example, even though we have a whole stack of plastic containers in our office pantry, I still choose to da bao food in the respective stall’s paper wrapping or styrofoam box because it’s more convenient. I also buy takeaway coffee like there’s no tomorrow—although I am fully aware that if everyone continues doing the same, there might not be a tomorrow to speak of.

That said, I understand the fight to prevent our planet from dying rapidly and the desire to believe in a cause that’s larger than ourselves. In fact, when I attended the climate change rally in September, I was heartened by the amount of activism from our youth. I even enthused about it in an article.

With the spike in climate change media coverage, I’ve gotten familiar with the ‘right’ thing to say and the ‘right’ way to say it, so it sounds urgent enough. But I often grapple with a severe case of cognitive dissonance because I would not have set aside time to educate myself on climate change if not for my job. In the end, what I write might be merely an attempt to convince myself that I am just as passionate in real life about climate change as I appear on paper.

It’s not that I don’t care about the earth. It’s that I don’t care enough.

Instead, it’s people like myself, who are intelligent enough to understand the science that’s driving the urgency of protecting the environment and the need to use such grave language to convey these messages. Yet we haven’t internalised the extremity by translating it into daily behaviour to make a change.

Unfortunately, we are—for better or worse—the majority. Making a significant improvement in the fight against climate change thus requires us to get on board.

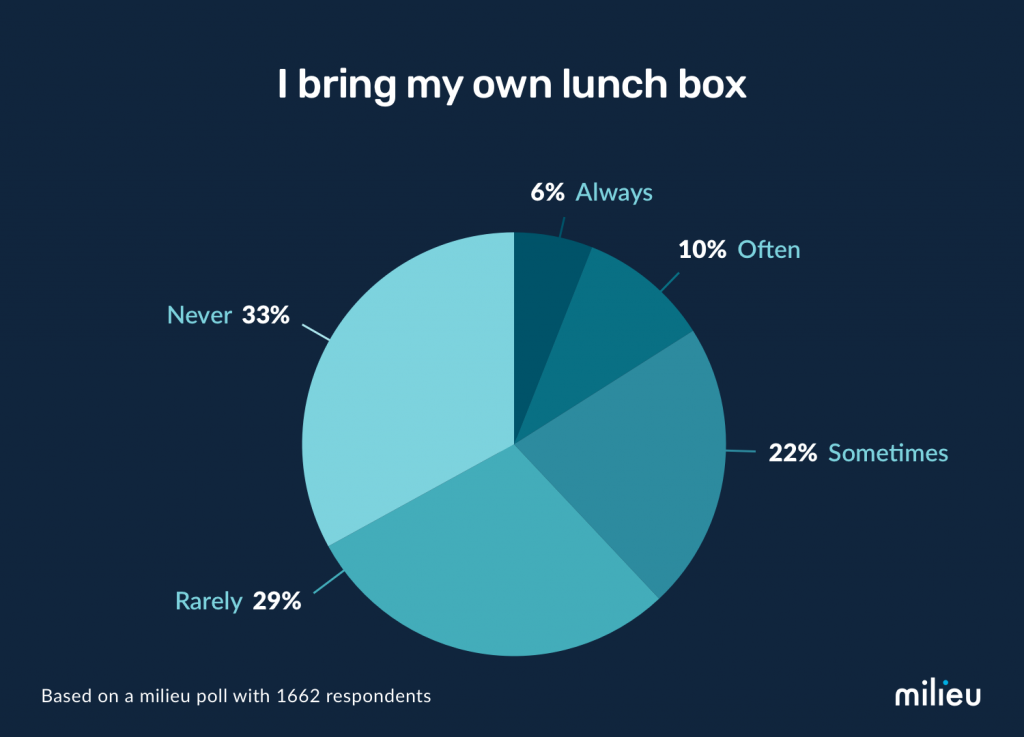

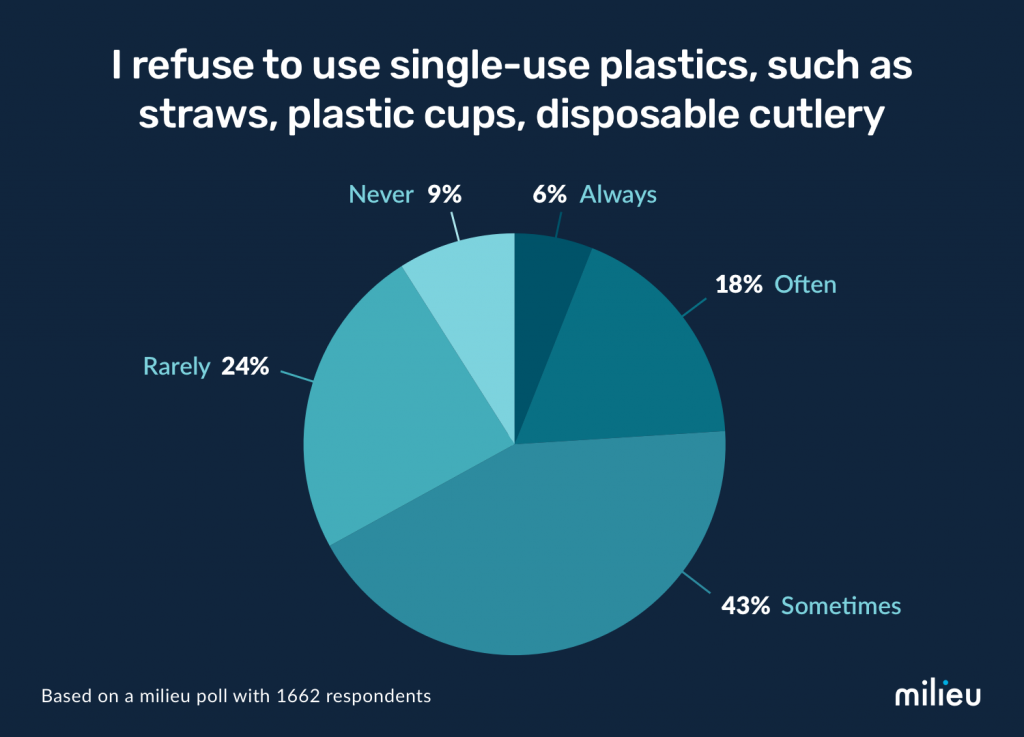

When we asked respondents how often they enacted each scenario on a scale of “always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely”, and “never”, all five scenarios saw majority of the respondents answer “rarely” and “sometimes”. On the contrary to what the loud minority on both ends of the spectrum might think, most people are in the middle.

Furthermore, when respondents were asked to consider all aspects of their lives and determine whether climate change ranked among the top three most pressing issues, 58% said no.

Arguably, this doesn’t mean that climate change isn’t important at all. But the first step to taking action is usually awareness—about both the origins of our present inaction and the mentality behind what will drive us to do something. The following reasons are by no means exhaustive nor mutually exclusive from each other.

At the rate that we’ve ramped up media coverage on climate change, it appears that the environment has gone from middling priority to utmost importance. More than 300 news outlets around the world, including the Straits Times, have teamed up to be part of global journalism initiative that pulls together resources on climate reporting, Covering Climate Now. At the Straits Times itself, the role of climate change editor was filled just in September.

The overnight gravity of climate change in the media is heartening, but not without its side effects. In this case, the problem is repeatedly positioned as something too gargantuan for any individual country, let alone country, to solve. Still, we are told that we must not give up hope and that our tiny actions matter.

But the sudden, consistent increase in news about the climate and how we can live more sustainably inevitably creates palpable exhaustion and helplessness. So it’s hard to see how something as seemingly inconsequential as refusing to use straws or plastic bags can save the earth.

The overwhelming influx of information about climate change is, of course, necessary. But it can also make us feel that the climate crisis will happen regardless, that there’s nothing we can do, and hence, that we shouldn’t do anything at all.

This sense of fatalism breeds powerlessness and helplessness, and eventually, apathy. We might not deny climate change, but we choose not to know. Unfortunately, our choice of indifference is a defence mechanism against the increasingly immense existential anxiety of feeling like we’re not in control of our destiny.

Along the same vein, it’s akin to pulling the wool from our eyes when it comes to meritocracy and inequality. When inequality was a buzzword in 2018, as per climate change in 2019, many of us needed to confront the reality that the upper classes would always have an inherent advantage in society, no matter how policies try to level the playing field. For many of us, this knowledge didn’t make us want to solve the problem of inequality, but instead pretend it doesn’t exist, by burrowing deeper into our own bubbles.

In the case of climate change, our sense of fatalism blinds us to the intrinsic benefit of our individual actions to live sustainably, regardless of whether they make a difference.

On the other end of the spectrum, people who fight climate change try to fight this creeping sense of fatalism at the same time. Perhaps, however, it’s not about fighting, diminishing, or fixing our fatalism, but accepting it without letting it define our actions.

Simply put, even if the world ends from climate change, we should still protect the environment. Not because we want to save the planet, but because protecting the environment is, in itself, a good thing to do.

Terrible communication

Most people discredit the importance of communication, especially when they believe that facts should speak for themselves. But the language we use to talk about climate change is, perhaps, the most important thing that matters in our fight. It might also be the most critical reason that people like myself don’t care enough.

As a Vox video explains, the “doom and gloom messaging is not conducive to engagement”. Similar to how news cycle fatigue might create a sense of fatalism, poor communication about this issue only reinforces feelings of fear and guilt, and hence, pushes people to adopt a passive stance towards fighting climate change.

The same video argues that creating social competition can act as a push factor for those in the middle to start caring more. As human beings, we do care about how we compare with others. In the local context, for instance, this can take on the form of awarding each housing estate with a tangible reward if they perform comparatively better than others when it comes to environmentally-friendly measures.

Separately, our communication about climate change focuses too much on individual effort, making it easy to chide celebrities or influencers, who promote messages of sustainable living, for being ‘hypocritical’. Since they live lives of excess that often generate envy, we disproportionately assign blame to them when we should focus on the big companies and industries who do more harm instead.

Unfortunately, the focus on an individual’s hypocrisy is unproductive since it implies the inverse as well: that our individual efforts can—and will—make a fundamental difference equivalent to policy-level change.

The problem isn’t that people like me don’t realise the importance of saving the earth. It is that this cognitive understanding hasn’t resonated on a fundamental, emotional level that changes our behaviour. We haven’t internalised the need to act on climate change.

On my part, I am simply too selfish to make climate change a priority. I have a finite pool of worry, and I am mostly concerned about the immediate things in my life, such as my relationships and my mental health.

Where climate change is concerned, spatial discounting explains why people like me stick to the status quo—or become more polarised—even when our newsfeeds are swamped with stories on the latest bushfire or dying polar bears. Research has shown that “if the message lacks personal or local relevance, people will be “less engaged”.

In order to target our inherent selfishness by moving us to act on something that will directly benefit us, climate change should feel more personal. One method is to adjust vocabulary and terminology, depending on who we’re talking to. For instance, in Thinking, Fast and Slow, author Daniel Kahneman states that our brains respond most decisively to things we know for certain. As a result, specifically detailing how climate change will immediately affect someone’s family, health, and career might make people take action.

Nothing to lose

This general rule of thumb can be as much applied to relationships as climate change: when we don’t fear that we’ll lose anything, we don’t act.

According to a Guardian article, “human brains aren’t wired to respond easily to large, slow-moving threats”. While many environmentalists say that climate change is happening too fast, in reality, it’s happening too slowly for our brains to compute that it requires our immediate and urgent attention.

In the same article, “loss aversion” in behavioural economics is defined as being more afraid of losing what we want in the short-term than surmounting obstacles in the distance. At the same time, our built-in “optimism bias” tends to irrationally project “sunny days” ahead despite evidence to the contrary.

So it’s not that people like me don’t realise we’re selfish. A more accurate term might, in fact, be that we’re habitually lazy. We cruise in our relationship with the planet, simply because we haven’t directly faced an instance that has triggered us into action. But similar to a relationship with another human, our inaction has already caused it to deteriorate.

None of the aforementioned reasons for the silent majority’s persistent indifference is meant to validate our problematic behaviour. Neither does the silent majority need any empathy or anyone to speak up for us, since we already form the majority.

But looking at how fervently opposite ends of the spectrum hammer home their points makes me realise neither party truly understands the mentality of those whom they should actually reach out to. The louder they get, the quieter the middle ground becomes.

If we want to save the earth—or, for that matter, make a change anywhere—then we must first begin to understand who our real opponent is.

In climate change, the enemy isn’t denial. It’s apathy.