As I watch myself dribble into a plastic cup, I feel a pang of disappointment. Because the plastic cup is wide and quite deep, my semen looks comparatively paltry and insignificant as it drips down the sides into a little pool at the bottom. Maybe it’s just the light in the room, but the sum of my come looks like half a mouth of spit.

I feel like I just let myself down. Even though this is only the first step in a long process that may or may not result in me being accepted as a sperm donor, it already feels like a mistake.

“Am I really just doing this for the sake of a story?” I ask myself.

The answer, unfortunately, is yes.

As a result, many couples who need sperm end up taking their sourcing overseas through local private clinics.

Unsurprisingly, the main reason for these dismal numbers is that many men feel it’s just “weird” or “wrong” to donate their sperm. A nurse also tells me that sperm donors are only reimbursed for transport costs. Unlike countries where you get some form of compensation for your contribution, this isn’t the case in Singapore.

For me at least, the fact that it’s been a surreal experience so far has made it all worth my time. Unlike stories I’ve heard about girly mags and porn on a television screen, there’s practically nothing in the wank room.

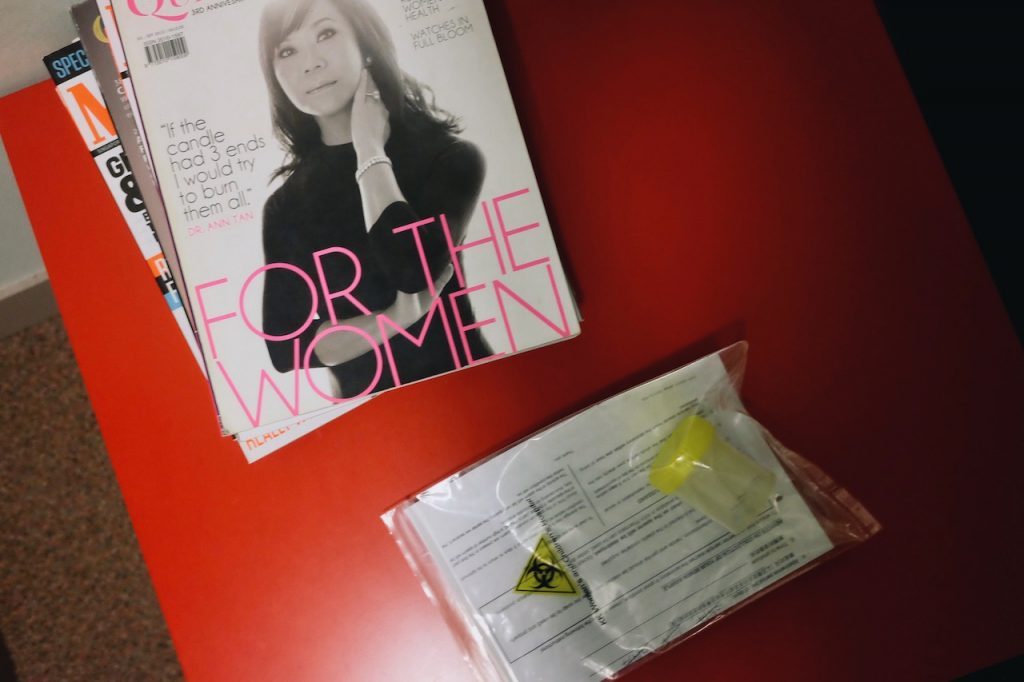

Flipping through the few generic women’s and lifestyle magazines available, I wonder what’s worse: no porn or porn that isn’t really to my taste? In 2017, thanks to 4G mobile data, this isn’t really a conundrum I have to deal with.

All the same, there something so amusingly conservative and Singaporean about the whole set up. I guess this is how deeply this country’s “family values” run.

When I’m done, the plastic cup goes into a transparent bag, which for some reason has a biohazard label on it. I pass it to a nurse, who proceeds to ask if it was ‘self-produced.’ A part of me is still reeling from the adrenaline rush, and the lingering residual shame makes me feel like it’s too soon to be having a conversation with another person.

Also, the question confuses me. It’s eventually clarified that yes, I did this myself, not with the help of another person. I infer from this that partners sometimes lend a helping hand.

For now, I’m waiting to find out if my sperm count is healthy enough for me to qualify as a donor. If I’m eligible, a series of tests will follow to make sure I’m completely healthy and have no history of genetic diseases. Once this is done, it will be a 6 month wait, another round of blood tests, and finally, 3 sperm collecting sessions.

I discover, however, that masturbating into a cup doesn’t turn out to be the most intense or uncomfortable part of this process. Instead, it’s the counselling session I have to sit through when I return to KK Hospital the following Monday.

With the counsellor, a bespectacled older lady, I run through a few generic questions. She asks why I’m doing this, if I’m aware of the consequences and the implications. Right off the bat, she tells me that I’m too young to be doing something like this.

“So what’s the ideal age?” I ask.

“It’s not about the ideal age,” she replies, “It’s just that … you are a bit young to be choosing to do something like that.”

“How do we know anything?” I counter. At this point, I’m getting a little bit frustrated. Part of it is because I feel like she’s judging me for how “young” I look, rather than how much sense I think I’m making.

In a way, it’s like I’m 11 again, listening to an adult tell me that I’m too young to know any better. I hear this over and over again: You’re a bit young to do this, maybe you should take some time to think about it.

I agree to think about it, but remind her that we never really know what we want. I’m determined to get the last word in, and explain that in the moment of any decision, we want what we think we want.

And then I start to get really annoyed, because she keeps finding ways to get back to the same questions. She’s supposed to be advising me, but she sounds more discouraging than neutral. At certain points, she gets argumentative, as though angling for an admission that I’m out of my depth.

“Isn’t this just supposed to be about my sperm?” I nearly snap.

I’m told that race is usually the biggest consideration, along with things like academic qualifications. She isn’t very forthcoming, but this makes me wonder how I’d feel if no one wanted my sperm: “Great, he’s Chinese! Wait, he’s only of average height, and graduated with a degree in English literature? Hmm, maybe not.”

Of course, I will have no way of knowing if this really happens. But I can’t help thinking about it.

For what it’s worth, these are the things you need to think about in the event that you do want to become a sperm donor:

If your sperm is used, what will your “children” mean to you, their legal parents, and to themselves? What if your children end up, by some coincidence, meeting and even dating the children produced through your donations? There’s no way of knowing this, but does the possibility alone bother you?

What if you feel differently about all this in the future? Is your choice to be a sperm donor just about you? Are there other people in your life whose opinions you need to consider?

Finally, why are you doing this?

This last question is, perhaps, the most redundant of them all. But when I’m asked it in a tiny room, in KK Hospital’s IVF Centre where the hopes and dreams of frustrated parents are quietly nursed amidst the sounds of children screaming and playing, it feels particularly poignant.

Why do we want children? Because it’s the next step after marriage? Because it’s an unexplainable desire that comes from some deep, nameless place within us?

These are questions that those of us who can conceive without difficulty will never have to think about.