A disturbing video made its rounds online over the weekend. The eight-minute video featured a 60-year-old man looking visibly uncomfortable while explaining a tired topic to an online persona.

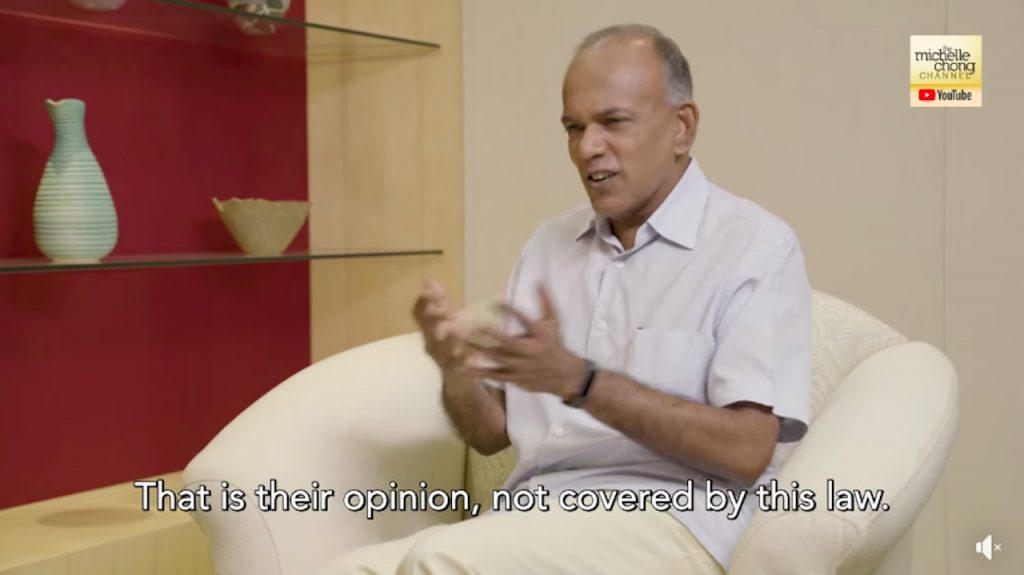

Specifically, Law Minister K Shanmugam sat down to discuss the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill (POFMA) with Ah Lian—local actress Michelle Chong’s onscreen persona.

The video, which was posted on Michelle’s Facebook page, gained significantly positive attention. Several commenters said the video was “nice and hilarious”, and liked that Shanmugam spoke to Ah Lian “on the same level”; they thought the “down-to-earth” video catered to “heartlanders”.

Others said the video was an “interesting and effective way” to present POFMA and clarify common misunderstandings about the bill.

To the minister’s credit, his answers were clear and consistent with his other media interviews and parliamentary sessions, even if you might not agree. In fact, of everything in the video, I took the least issue with the minister himself; I even felt an ounce of sympathy for him.

This meant using simpler words and even jesting with her, which made him appear ‘down to earth’ and ‘relatable’.

More importantly, the video wanted us to believe that it stemmed from the good intention to break down policies for the layman. Essentially, it can be seen as a PR campaign for POFMA itself—and this act, more than turning Minister Shanmugam into an online celebrity, can prove far more problematic.

Admittedly, I’ve always really liked Minister Ong for reasons unrelated to the video or this article. So it didn’t help him or the Ministry of Education that the video’s concept felt just as antiquated as Ah Lian’s.

Similar to Minister Shanmugam discussing POFMA with Ah Lian, the objective of getting Minister Ong to answer irreverent Instagram questions from kids was probably to alleviate public concerns over the new streaming measures. The video also broke down complex reasons for enacting policy into lighthearted, entertaining, and humorous one-liners, showing off the minister’s comic timing.

Throughout the comments, one common sentiment surfaced: for an Education Minister, he was “pretty damn cool,” as though being “sassy and witty with his comments” had been mutually exclusive to being a minister.

“I hope all policies can be explained this way.” said another commenter.

Minister Ong was personable and charming—two character traits rarely associated with government leaders that present well on social media. Coupled with an ‘innovative’ concept to reach out to Gen Z, the video inadvertently turned a politician whose decisions affect millions into an online celebrity, distracting from legitimate concerns about policy changes.

After 2.5 minutes of watching Minister Ong tackle inane questions like “can MOE employ chiobu teachers” and “what did you get for PSLE”, I got the disconcerting sense that I was supposed to believe ‘everything would be fine’, simply because we had a ‘relatable’ minister at the helm.

This sort of PR is primed for virality on social media, and puts ministers in a position where they are expected to entertain rather than be held accountable. In addition to our lack of understanding about how our political system works, this makes us less able and interested to criticise their policies.

As irksome as these videos might be, Singaporeans are not completely at fault for wanting this degree of relatability from our politicians, since we continue to fall for the PR over and over again.

From eating in hawker centres to recounting funny anecdotes about their childhood on national radio, we lap up these instances that reveal a ‘crack’ in their serious facade. But these schticks become especially apparent when they’re used as a public relations tactic to ‘soften’ a minister’s public image, shortly after their respective ministry announces far-reaching and complicated policies.

For instance, two years ago, a brilliant Chinese New Year ad about cutting down on sugary foods during the festive season featured typical stunts, backdrops, and characters from Chinese historical dramas to reach out to the older generation. The ad worked; it boasted equal entertainment and educational value, and didn’t discredit the target demographic.

Even everyday messaging has been done tastefully. The Ministry of Education regularly uses simple infographics to broach sensitive issues with parents, such as reminding them to let their children play and get enough sleep.

Perhaps then, Ah Lian’s POFMA video should have addressed the reasons that the bill exacerbated Singaporeans’ distrust in the government at all. On the other hand, the video with Minister Ong could have featured tough questions about the new streaming policies, if the government truly wanted to demonstrate Minister Ong’s prowess in tackling difficult questions in entertaining ways without being overly reductive.

Otherwise, when we continue to allow our obsession with relatability to put the focus on a minister’s personality, this becomes a red herring that distracts from actual policy issues.

At best, these videos are a superficially amusing few minutes which you might remember for the concept but not the message. At worst, the videos are a poor PR stunt, pandering to a false impression of the group of people whom the government is trying to engage.

And while seemingly innocuous, the latter would inevitably further alienate a voter base that already feels disconnected from the nation’s decision-making elite.