When I was on the MRT platform the other day, I saw what I thought was an action movie playing on one of the screens. Masked men pointed guns at hostages and police officers closed in with rifles drawn. Curious, I edged closer to figure out what was playing.

As I got closer, I noticed that the police officers were wearing SPF uniforms.

“Wow, Singaporean TV series’ actually have damn high production values,” I thought. Then the video ended and an SGSecure banner flashed across the screen.

I had seen SGSecure posters before, but had passed them without much more than a glance. This video, on the other hand, was gripping, and frankly quite scary. It reminded me of some of the very real terrorist attacks that have occurred in my home country of the United States: the Orlando nightclub, the Pittsburgh Squirrel Hill synagogue, the Charleston church …

My knee jerk reaction was a feeling that even in Singapore, a place that I have never worried about being violently attacked in, I wasn’t safe.

I figured others must be jarred as well, but I was the only one watching the ad, let alone freaking out.

“Most governments try to play down this threat, perhaps because they see counterterrorism as exclusively the job of government agencies with no role for a ‘prepared’ civilian population. There is of course a risk that highlighting the potential for Islamic radicalism, for example, might cause tensions in society, but one has to weigh that risk against the potential benefit of having citizens who are prepared in the event of an attack,” he tells me.

In the wake of terror attacks in the West, there has inevitably been a huge amount of media attention and renewed paranoia over terrorism. At the same time, this is by many measurements totally overblown. According to the Washington Post, no more Americans died in terrorist attacks in the period between 9/11 and 2015 than were crushed to death by their furniture or TV sets.

The goal of terrorism is to strike fear into the hearts of their enemies—to terrorise. As such, most governments seem to focus exclusively on promoting unity and resilience in the wake of such attacks. Not so much in Singapore.

Yet while I began worrying that the SGSecure campaign might be having negative side effects like making people paranoid, most people I talked to didn’t seem to give it much thought to at all. Indeed, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), as part of its 2019 Terrorism Threat Assesment Report, found that only 1 in 5 Singaporeans actually felt that an attack might occur within the next 5 years, a decline from last year.

At least when it comes to the goal of making people more concerned about terrorism, SGSecure is doing a woeful job.

Part of the reason for SGSecure’s ineffectiveness is simply poor communications. Most of PR I’ve seen have looked like action films interspersed with dire messaging claiming that terrorism is “not a matter or if, but when”, and that it can happen “anytime, anywhere”.

Others seem more intentionally comedic, like it could just as easily be satirising SGSecure as promoting it. Take this MHA commissioned rap song produced by SGAG promoting the SGSecure app, for example.

The government also commissioned internet personality Michelle Chong, aka Ah Lian to do an SGSecure workplace promotional video, also quite cringe-worthy. There are also the eyeball people cartoon promotional videos, which come off as plain creepy.

Poor communication may also be responsible for meme-ification of the SGSecure app.

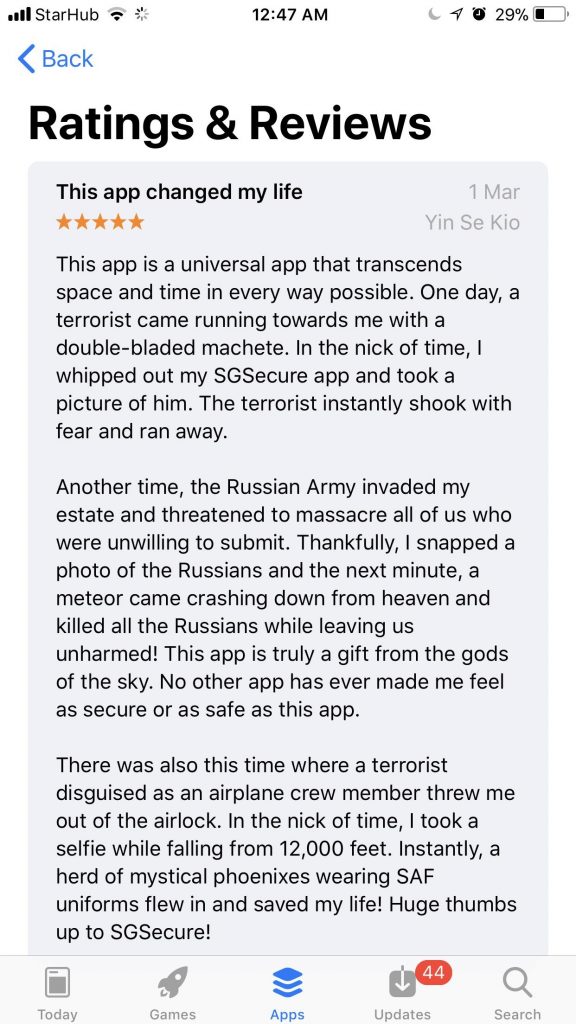

Since the app was first released, hundreds of fake reviews have been posted on the app store claiming the SGSecure app saved them from some outlandish disaster, often involving fictional Marvel villain Thanos. The vast majority of reviews on Google Play Store are fake, and those that aren’t fake claim that the app’s photo reporting feature doesn’t even work, which seems tragically ironic itself—imagine dying in a terrorist attack while trying to take a picture with a security app that doesn’t work.

One of my colleagues presented a good way of understanding why Singaporeans don’t react to this sort of government PR in the same way a Westerner like myself would. He said that Singaporeans tend to view their government as overprotective parents; every time you go out late at night, your mom is going to tell you to watch out for thieves, rapists, etc.

But you never take it seriously. It’s just mom overreacting, as always.

Rather than making you worried, it just shows that mama Singapore is always ready to take care of her baby citizens.

Head of National Security Studies at NTU Dr. Kumar Ramakrishna says, “Traditionally, providing for homeland security has been seen as the job of the government by the Singaporean public, and the government has always been regarded as doing a good job. Moreover, the absence of actual successful terrorist attacks, like the ones we have seen in Israel or even London in recent years, has played a role in preventing some Singaporeans from taking the terrorist threat seriously.”

He adds, “As an analyst, however, I think that we should not be too complacent. An attack in Singapore using everyday objects like cars and knives are very plausible, and I think that the government wants people to realise that Singapore is a target.”

But even if an attack on Singapore is inevitable, I still think that Singaporeans’ rejection of SGSecure is better than following it wholeheartedly.

One of the main tenets of SGSecure is constant vigilance: if you see suspicious individuals or unclaimed bags, you should report them immediately. If SGSecure were taken seriously, then it would erode the sense of communal trust that I find to be one of Singapore’s greatest virtues.

Pretty much nowhere else in the world can you leave your bag unattended at an open food center and reasonably assume that it won’t get stolen, and that no one will think it is an explosive device. To me, eroding that for the purpose of attaining marginally greater security isn’t worth it.

Even if an equivalent number of people per capita died due to terrorism in Singapore (as in the United States in recent history), this would equate to fewer than an average of 1 person every year.

I anticipate many would say that Singapore is a small state in a perpetually vulnerable position, and therefore cannot afford to take a relaxed stance on security. While this small state narrative is reasonable when it comes to threats like invasion by foreign powers, it is not when it comes to terrorist threats.

Professor Mukherjee explains, “When it comes to terrorist threats like those alluded to in the SGSecure campaign, Singapore being a small country actually helps it protect itself from internal threats. Its small size makes it relatively easier to control the movement of goods and people that might be involved in a potential attack. If you think of how the terrorists who attacked Mumbai in 2008 arrived by boat, something like that would be much harder to carry out in Singapore due to the government’s ability to effectively monitor and patrol its maritime environment.”

In light of Singapore’s relatively high ability to neutralise terrorist threats even without community preparedness, I reached out to MHA get a better picture of why the government feels that SGSecure is necessary. They declined to comment.

Additionally, some aspects of community preparedness are incredibly controversial due to their adverse effects on mental health. Many have argued that the realistic active shooter drills often conducted in the United States, because of the psychological trauma they cause, do more harm than good.

While it might make Singapore marginally more secure, ‘preparing’ Singaporeans will come at a great cost. There will no longer be the distinctive sense of mutual trust and respect that makes Singapore feel safe. On top of that, it may make Singaporeans paranoid in a way that is psychologically harmful.

For me personally, I don’t plan on being more vigilant towards terror attacks in Singapore. If it happens, it happens. Otherwise, I am not going to worry about possible, yet incredibly improbably tragedies. I am going to continue to trust the strangers I meet in Singapore, continue to not freak out when I see unattended bags, and stop paying attention to ostensible action movies on the MRT.

I hope Singaporeans continue doing the same.