“I’m so tired.”

“Ya … it’s like that lor.”

“What you want to eat? Share mala?”

As we took our seats, one of them commented, “Our hawker centres can’t be cultural sites until the seats have backs.” As if on cue, everyone erupted into a chorus of complaints about their various back sores and aches.

I chalked up this enthusiastic discussion to age—we had all turned [sensitive information redacted] recently, so, I thought, bodily failings came with the territory.

But when I was with another group of friends—who were, very inconsiderately, younger than me—the conversation turned again to back problems. I started to wonder if something was going on.

What was up with our backs? Was this a millennial thing, like buying avocado toast and air-fried Brussels sprouts instead of a house? Or is it just something that happens naturally as we settle into the long dry decades of working? What is this chronic, prevalent back pain symptomatic of?

“A dull ache or soreness.”

“Very stiff. My shoulder cracks.”

“It permanently hurts on the right side.”

“Like someone hitting me with a spoon 24/7.”

Soreness. Stiffness. Pain. Hurt. Being hit by a spoon 24/7.

This grasping told me that, even as we suffer from back problems on a daily basis, we don’t quite understand why or what they are; neither do we have the language for it. We know only that like life, it hurts.

So I approached Shwikar Aljunied, a physiotherapist at The Physiolink, for enlightenment. As a physiotherapist who has been treating Singapore’s national athletes for 24 years, she’s seen and tended to all sorts of physical dysfunctions. (Pre-emptive disclaimer: this is not a sponsored post.)

In other words, your back is kind of sensitive.

More significantly, Shwikar pointed out that she has seen more young people with back problems hobble into her clinic compared to a decade ago.

From the perspective of the sufferer, this statistic is not surprising. All the people I spoke to know others with back problems, as if we are all connected by an invisible thread of misery.

“I have at least 8 [other] friends who struggle with [back problems],” another said. Shocked by the number, I looked at her incredulously—is it possible to have so many friends?

“It’s a real epidemic,” one of them even concluded.

In any case, after more digging, I found out that up to 69% of young adults have experienced back pain; more strikingly, a study conducted in Poland found that 76.2% of children and youth aged 10-19 have experienced back pain.

Before dismissing this result as unique to specific Polish factors, note that the study concludes that “the prevalence of back pain in children and youth living in southeast Poland is similar to the frequency of occurrence of such complaints occurring in peers in other countries.”

As Singaporeans, we top all global rankings—from public safety to inequality—so it’s not at all impossible that an outsized number of Singapore children and youth experience back pain much more excruciating than their peers in other countries.

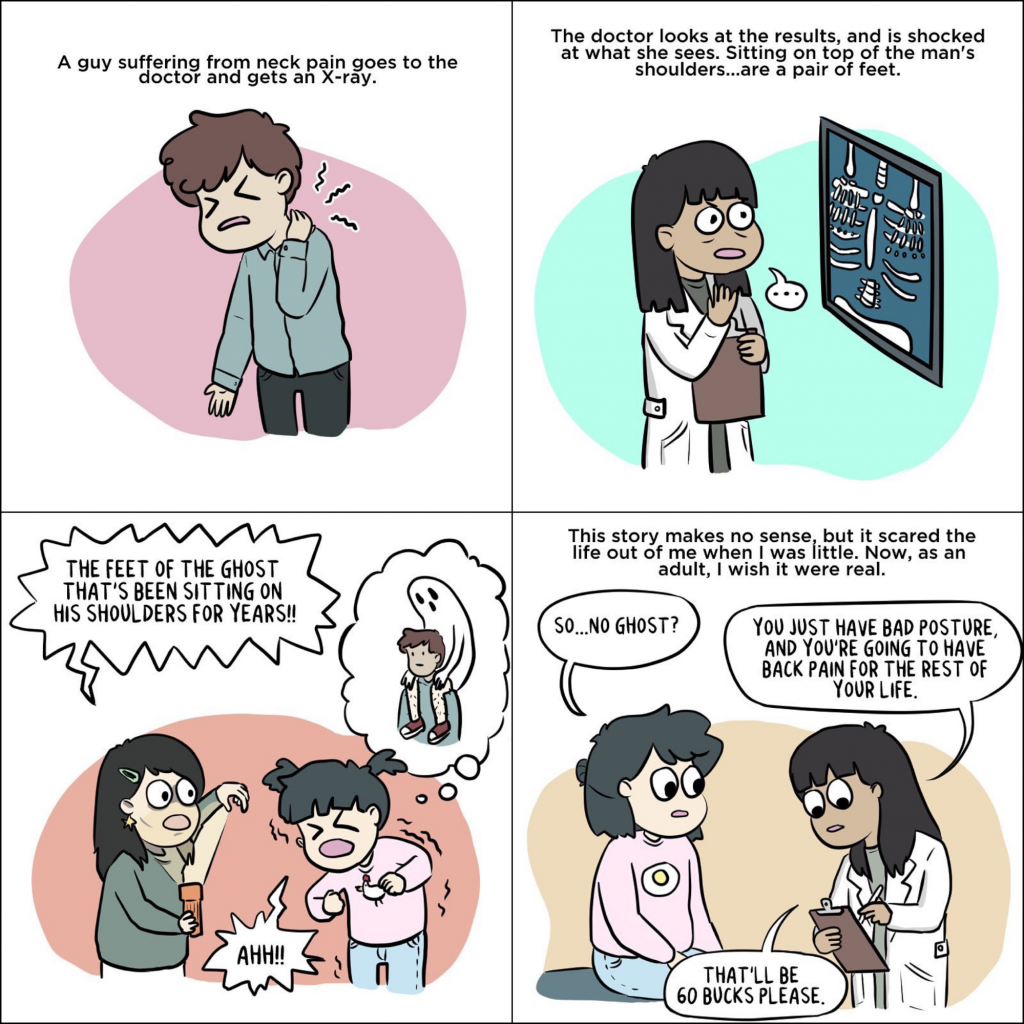

You don’t need to be a Member of Parliament or convene a Committee of Inquiry to determine why we’re all suffering from back problems from a younger age:

“Long hours of sitting and writing with bad posture.”

“Company practises hot-desking where each employee is given a laptop … so it is hard not to be hunched over the laptop all day. Colleagues have back pains [because of this too].”

“Probably my terrible sitting posture. You get so engrossed in your work … that you just end up sitting badly for hours on end without realising.”

“I believe work is definitely one of the key reasons. My work requires me to sit behind my desk most of the time and sometimes I have to clock overtime as well so that doesn’t help. Friends and colleagues who have desk-bound jobs [complain about back problems] too.”

The terms that are repeated: work and posture, long hours of sedentary work, being chained to your desk.

We’re all aware of them; all victims of them.

Shwikar corroborates these anecdotal accounts, explaining, “The body is made to move; the more we move, the more the joints get lubricated. Sitting for long periods adds a lot of pressure on the spine. It distorts the normal spine alignment. Thus over time, [sitting for long periods] will cause stiffness, muscle imbalances and bad habits.”

This correlation is so self-evident and widespread that I probably don’t have to cite medical papers to convince you. But I’m going to do it anyway: “Evidence suggests that risk factors for the onset of neck and low back pain in office workers are different from those identified in a general population.”

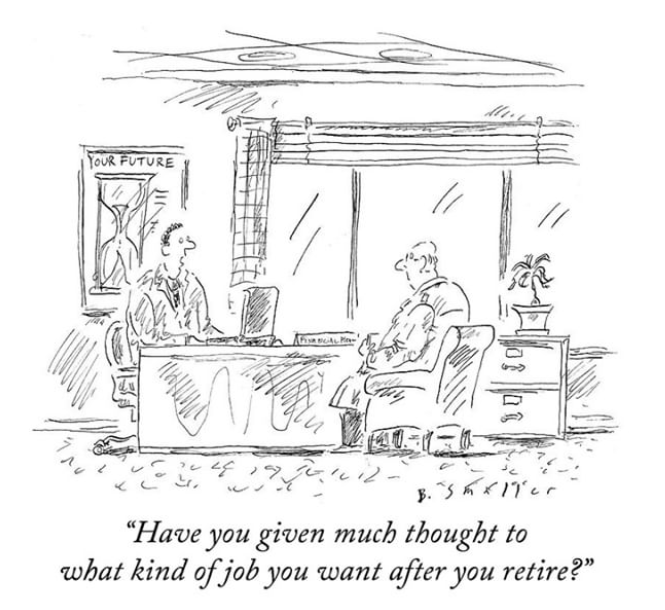

In fact, today, the back-problem complaint seems to have taken on a sheen. Much like the “I’m tired all the time” lament that actually encodes how busy—in other words, how happening or productive—its afflicted are, back-problem complaints are now uttered with a kind of perverse, masochistic pride.

It has become an act of a virtue signalling.

It says, “At my desk, I’m plugged into the global chain of capital.”

It proclaims, “I’m a productive member of society.”

It exults, “I work to the limits of my body.”

Consciously or not, it promulgates a puritanical work ethic, an attitude towards work that the narrative of Singapore’s development has conditioned us to imbibe.

This attitude is not new. Our parents were the first to drink the Kool-Aid. Exposed to newer options like kombucha and kefir, we millennials have the luxury and privilege of questioning the effects of our work on our bodies, though not enough of it to stop drinking anything at all. Hence, the cognitive dissonance of embracing the pain.

With the recent discourse on owning and reclaiming our bodies, in terms of sexuality, reproduction, skin colour, and so on, perhaps it is time to turn our attention something as fundamental as the healthy functioning of our body.

But even as we are aware of the circumstantial causes of our back problems, only one person I talked to pointed to how back problems are symptomatic of a larger problem.

It’s not something as reductive as work or capitalism, for there are many forms of work in a capitalist system that do not tax our bodies this way. Instead, it’s our—and society’s—assumption that, I quote her, “Pain is part of the job. It’s our fault that we are hunched over and we need to adapt our bodies to the task.”

And it’s not just our backs that suffer. Office workers who suffer from back problems are likely to experience feelings of depression, exposure to hostile work, increased stress, anxiety, job dissatisfaction … and so on.

Of course, back problems do not cause anxiety and depression, nor vice versa. But the strong comorbidity amongst all these factors says one thing clearly: something is wrong with the way we work and the way we expect to work, and we—not just millennials in Singapore, but people of all ages worldwide—are suffering for it. It seems like a millennial problem because we’ve only begun questioning it.

And yet countless people have tried to warn us about it. A German with a fabulous beard wrote, as early as 1844, that work “mortifies [the worker’s] body and ruins his mind,” making him a “mere fragment of his own body,” “a living appendage of the machine.”

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, two Very Smart People, predicted that our modern organisations like “the State, army, factory, city, Party, etc.”—institutions where we devote our bodies to work—will cause our bodies to be “cancerous … stuck in a state of replication; its production is malignant.”

What is cancer? A family of disease characterised by uninhibited cell growth in which our body cells reproduce themselves endlessly, like someone retweeting himself perpetually hoping his tweet goes viral.

Deleuze and Guattari (name a more iconic duo… I’ll wait) use the idea of cancer to suggest that this is how we, and our bodies, act when we enter these aforementioned systems. We work according to certain strictures and the work we do generates new work that we have to do.

When the growth of cancer cells spirals out of control, they coalesce in a mass and become a malignant tumour, threatening its very host, the human body.

By way of this analogy, when we lose control of the way that we work, our problems snowball. And work, which was supposed to enrich our lives, starts to pose health threats.

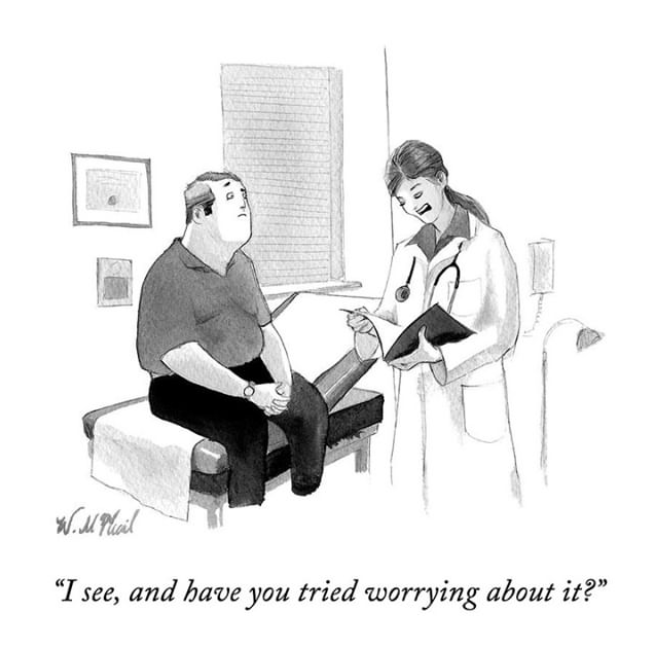

Shwikar recommends that corporations can help to minimise back problems by providing adjustable monitors, ergonomic chairs and tables, or stretching breaks every hour. These are certainly practical suggestions that should be adopted by all companies, but at the end of the day, they address only the symptoms. It’s kind of like how cough syrups suppress your cough by numbing your throat muscles, but do not kill the bacteria causing it.

Still, we have to ask: what can we do? Surely we can’t hope to dismantle the whole capitalist system (as the aforementioned fabulous bearded dude wanted to) and be termed a conspiracist. Moreover, it is not so much capitalism that is hurting us directly but the things we have tacitly acceded to.

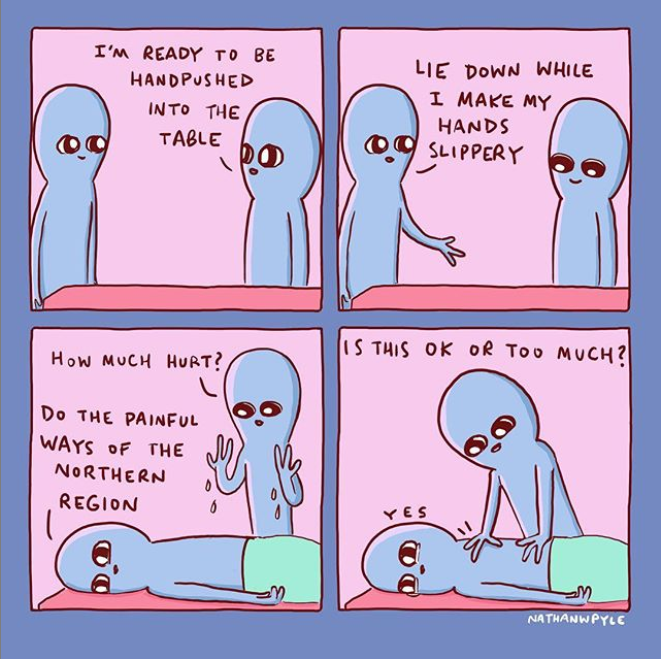

And even if we wanted to begin by alleviating the pain in our backs, we can’t escape our desk-bound jobs. Physiotherapist visits, BackJoy purchases, getting pummelled into submission by the tui na auntie, all cost money. And we get money by … working at our desk-bound jobs.

I really wish I could offer something empowering and inspiring to end my article. Something hashtaggable with the potential to start a movement, like #IveGotMyBack.

But I don’t.

The most I can say is, perhaps we millennials need to stop lacing our back-problem complaints with hidden pride. There’s nothing wrong with feeling pleased with our productivity at work, but we should neither valorise our pains nor absolve its perpetrator.

Besides, if it’s pain you’re after, there are much more pleasurable and consensual ways of obtaining it.

Like eating da la mala, of course.

The numbness it induces in my mouth and soul is the perfect distraction to the back pain I got from writing this article.