All photos by Xue Qi Ow Yeong and Zheng Yi Yap for RICE Media

When you live in one of Singapore’s earliest HDB flats, history might sometimes feel more like a weight than a blessing.

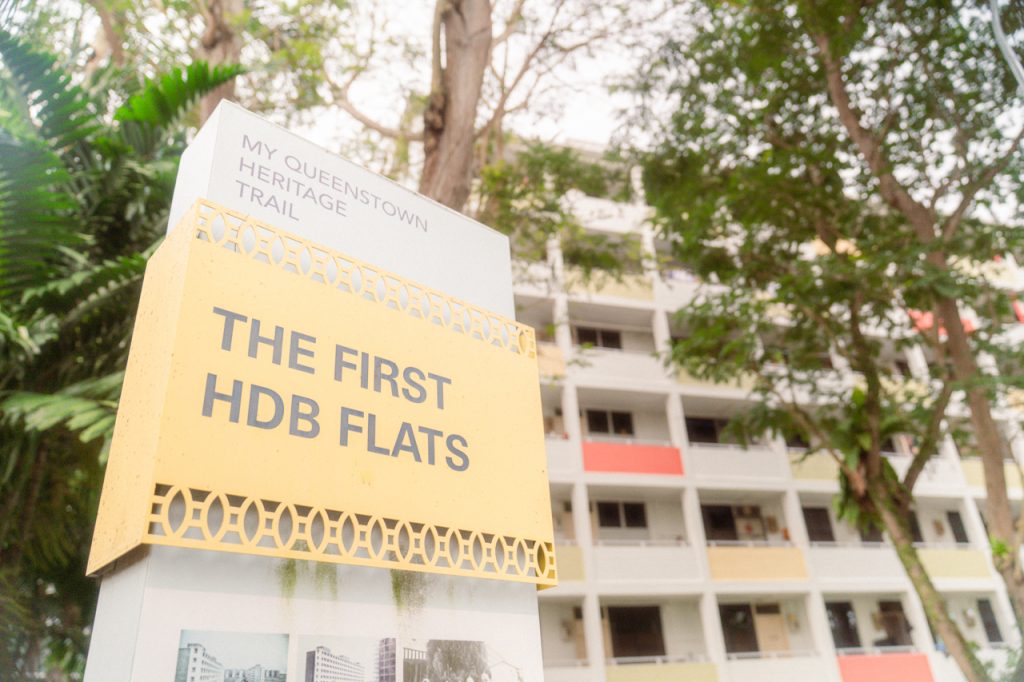

Blocks 45, 48, and 49 on Stirling Road were handed over to residents in 1961, before Singapore’s independence. These Queenstown blocks are now part of our heritage. They’ve been accorded a place in the My Queenstown Heritage Trail, although they haven’t been designated as conserved buildings.

When we think of ‘preservation’, naturally, the idea of maintenance and structural integrity comes to mind. You expect polished walls, curated plaques, and a collective pride that keeps memories alive.

Instead, they appear tired and run-down—like history forgot to take care of them.

We went there expecting stories of pride, maybe some nostalgia. Instead, we found leaking ceilings, peeling walls, and corridors that had long surrendered to time.

But in the quiet in-between—between past and present, neglect and resilience—live the residents. They are content.

Living in a Fading Postcard

Walking along the foot of the block, you find a handful of stubborn businesses—a bubble tea stall, a hawker stand, a community mart—that still cling on to life.

Most of the other storefronts lie shuttered, their metal grills rusted and locked. Upstairs, the buildings grow quieter still. Windows remain shut tight, hiding empty flats or guarded interiors.

We meet 80-year-old Ms Fang, a resident on the top floor of Block 49. Her dimly lit living room flickers from the light of a television screen.

She’s lived in Stirling Road with her son for 40 years, watching her community shrink and its vibrancy fade. Many of her neighbours have moved or passed on, she says.

“I’m not sure if the government has plans for this place,” she says. “My ceiling has been leaking for years.”

She mentions how little has been done despite her countless calls to the authorities for assistance. Heritage status doesn’t fix leaks, we suppose.

“They came and took photos, but nothing has been done. Every time it rains, I still have to mop the floor.”

A few floors down, we encounter a 90-year-old woman of fiery spirit and high conviction. She declines to share her name, but she’s got plenty to rant about. Alone and unable to leave her house due to mobility issues, she tells us fiercely about the noisy neighbour who disrupts her peace and escalates their disputes into threats.

Despite repeated complaints to the authorities, nothing has changed, she says. Yet, in her anger over noisy neighbours and cracked floors, there’s fierce survival. She was almost exhilarated to find someone who would listen to her. Her raw, relentless voice is a reminder that heritage is not just about buildings, but about the lives inside them—lives often pushed to the margins.

We pause for a drink at one of the stalls under Block 49. Mid-sip, a commotion unfolds—plainclothes policemen are arresting a resident. We watch, transfixed. Mary, the stall owner, barely blinks.

“Does this happen often?”

“Every now and then. It’s not the first time for sure”.

Mary’s modest stall stands as a relic fighting a losing battle. She’s been serving the block’s dwindling customers for 20 years. But a few streets over, the sleek, air-conditioned Margaret Market has sprung up, drawing away the footfall.

Mary has tried to pass her business to younger family members, but her appeals to transfer the shop’s lease have failed so far, she says. And if she surrenders the unit back to the government, she’ll have to pay out of pocket to undo all of the shop’s renovation work and restore it to its original state.

So she stays, a lone soldier in a neighbourhood caught between the pull of the past and the pressures of modernity. She’s resisting erasure. For now.

A Neighbourhood of Contentment

Amid these struggles, there is also a surprising calm.

Mr Goh has lived at Stirling Road for 40 years with his younger brother. He surprises us with a warm welcome and a cup of water, ushering us into his flat without hesitation.

Until recently, he worked as a cleaner. He had to stop after undergoing eye surgery. When we ask about the state of his home, he gestures toward the ceiling, pointing out where the leaks have finally been patched up.

We probe further, trying to understand if there were any qualms about living in this area. He smiles, replying with a sense of gratitude, “平平安安,开开心心就好“。(As long as we are safe and happy, that’s enough.)

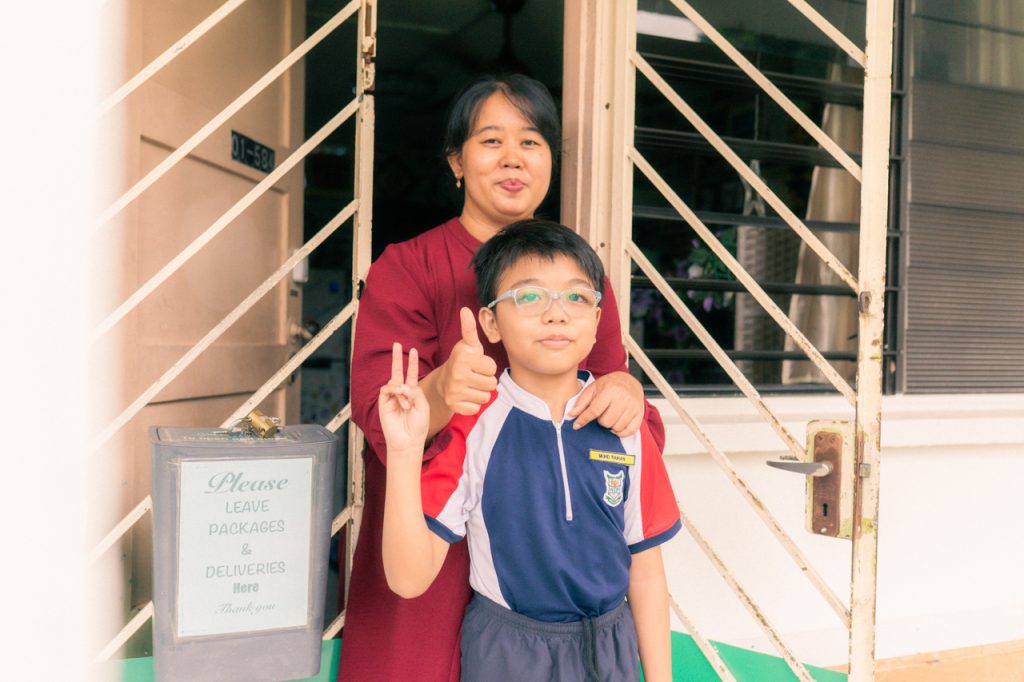

Ms Li, 70, stepped out eagerly when we approached her unit.

“What’s it like living here?”

“It’s not very convenient, but it’s okay.”

Sometimes the corridor floods during heavy rain, and the water gets into her home, she explains. She and her neighbours have submitted complaints about it, to no avail.

“We fixed the issue ourselves by opening one of the drainage covers,” she says.

“Then are you happy?”

“Yes, my children treat me well, and they visit me every week. My son recently bought me an iPad. To be honest, the people residing here are quite easygoing and we don’t ask for a lot,” she muses.

“Most importantly, don’t overthink things. Stay healthy, and be happy and content with life.”

Jackson Lee, a man in a wheelchair who crosses our path twice during our visit, has been living here for 25 years. He is one of the easygoing residents Ms Li speaks of.

“Money is something you cannot bring to your grave,” he exclaims. He tells us he’s happy to live one day at a time.

Nearby, elderly couple Mai Zhu Chen and Wang Fong Yun have spent over a decade at Stirling Road.

“Do you like staying here?”

Mr Wang lets out a hearty laugh. He says that the place is an affordable rental flat, and they didn’t have much choice since neither of them is working. He adds with a smile, “能吃,能健康,开心就好“。(As long as we can eat, stay healthy, and be happy, that’s enough.)

Yet, beneath these expressions of contentment lies an incongruence. These blocks are highlights on the My Queenstown Heritage Trail. But what does the honour of being the first HDB flats really mean when ceilings drip water, corridors flood, and residents’ calls for help go unanswered?

What this place taught us is that preservation is not about bricks, mortar, or plaques. It is about dignity. It is about the shared buckets of water used to mop up floods, the community getting together to hotfix issues, and the furious refusal to be silenced.

Singapore’s story is one of progress. But progress is never clean or easy. It can leave behind the very people who helped build it.

Stirling Road is a snapshot of that tension—a neighbourhood caught between the warmth of history and the gritty truth of reality.

When the plaques fade, it is the people who live, suffer, laugh, and fight within these blocks that will keep Stirling Road alive.