This story was brought to you by the Singapore Maritime Foundation.

All images by RICE Media.

Singapore is the little island that could, and the sea is our secret weapon.

We have neither vast land nor natural resources. But what we do have is a strategic geographical location and the sheer will to chart our own course. To that end, we built a thriving free port and maritime hub, riding on the tides of trade that propel us forward.

Our ancestors travelled here by sea, and the salt still runs through our veins. But the action is no longer just out there on the open water. The buzz is also happening in the offices of CBD skyscrapers, in innovation labs where engineers are piloting new technology, and on the screens of data-driven analysts transforming Singapore’s maritime industry.

The new wave of Singapore’s maritime future isn’t just about massive ships or colossal containers—it’s about big ideas and bold people.

Now more than ever, we’re not just riding the tides; we’re making them. These are the stories of Singaporeans charting the course.

The Green Tide

Alex Koh has been at Seatrium for 17 years since graduating with a degree in electrical and electronic engineering. As the deputy lead of the company’s electrification programme, he’s been given a monumental task: help shift the sector away from its long reliance on fossil fuels and towards a cleaner, electric-powered future.

Out at sea, onboard a vessel known as the Floating Living Lab (FLL), Alex and his team are testing what that future might look like. Back onshore, his team analyses the data collected from the FLL through sleek screens and fancy interfaces—but most of the work still comes down to tinkering with tools and technology.

At its core, the Lab is a testbed: a floating charger powered by advanced energy storage systems. Think of it as a giant battery at sea, where new green technologies are put through their paces before being deployed at scale. The goal? A harbour filled with electric vessels instead of the ones chugging on diesel. It’s a bold dream—greener maritime transportation, powered by innovation and grit.

But first, the systems need to be safe. Reliable. Proven. And that’s what Alex does: de-risk the technology, iron out the hiccups, and make sure Singapore’s maritime industry is ready as the tide turns.

Into the Deep

Hidden below the surface of Singapore’s busy ports and coastlines is a sprawling network of critical infrastructure—subsea internet cables, oil and gas pipelines, even structural foundations that keep things running smoothly above ground.

But inspecting these systems has traditionally meant sending divers down into the unknown: dark, pressurised, and sometimes dangerous.

That’s where Goh Eng Wei and Grace Chia come in. The husband-and-wife team are the minds behind BeeX Autonomous Systems, a homegrown company developing underwater robots designed to make inspections safer, smarter, and more scalable.

Their flagship machines—like the A.IKANBILIS and BETTA—are built to be the ideal companions for divers. Beneath their streamlined shells are cutting-edge sensors and software that allow them to navigate murky waters, map underwater environments, and collect vital data without needing to put a human in harm’s way.

The promise of BeeX technology isn’t just in its novelty. It’s in its real-world impact: reducing the risk of workplace accidents for divers, extending inspection times, and offering a consistent, reliable way to monitor ageing infrastructure. And unlike humans, robots don’t get tired or disoriented.

What BeeX offers is a new partnership between man and machine. Divers will continue to play a pivotal role, especially where nuance and adaptability are needed. But with autonomous systems doing the heavy-lifting in high-risk zones, the future of underwater work might look a lot safer—and a lot smarter.

From Printer to Port

Wen Sheng Toh never imagined that his love for 3D printing would take him out to sea.

A self-professed tinkerer, he started with small desktop printers and open-source designs. Now, he’s an Additive Manufacturing Engineer at Pelagus 3D, a company pushing the boundaries of what 3D printing can do, especially for the maritime industry.

”When I saw this job, I was like, ‘Is 3D printing really a valid thing that people do for a living?’”

At Pelagus, Wen Sheng helps create spare parts and components for commercial vessels. Not from warehouses or factories, though, but from digital files and printing beds.

What used to take weeks to ship can now be produced within days—or even hours. But beyond speed, it’s about precision, adaptability, and reducing the downtime that costs shipping companies millions.

To get it right, he often boards the ships themselves, working closely with engineers to reverse-engineer broken or outdated parts. Out at sea, there’s rust, salt, and limited resources. But that’s where Wen Sheng unexpectedly thrives—translating physical problems into digital solutions.

In an industry that is transforming itself, Wen Sheng and his team are proving that innovation doesn’t always come in the form of sleek apps or expensive gadgets. Sometimes, a printed part could well be the missing piece to the puzzle of streamlining the manufacturing supply chain.

Pedalling Where No One Has Before

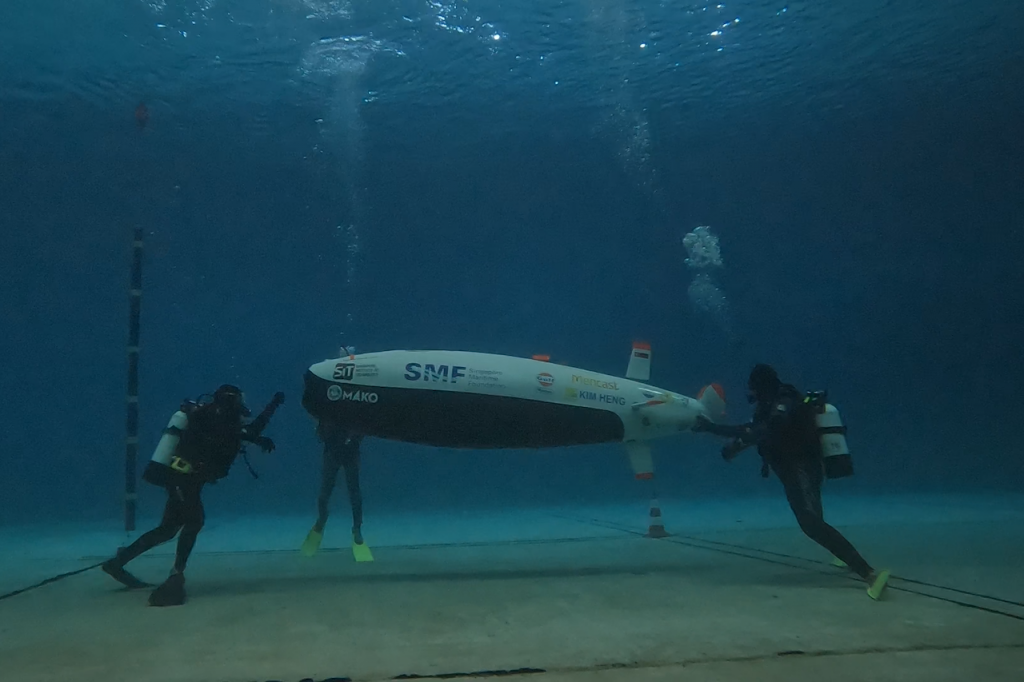

When Ryan Tan signed up for the European International Submarine Races (eISR), he wasn’t joining an existing club or project. He was building something from scratch—literally.

As the Captain of Team Nautical Knights from the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT), Ryan led a group of naval architecture and marine engineering students in designing and constructing Singapore’s first-ever human-powered submarine.

From concept to construction, every stage was a first. They used 3D modelling software to create a viable design, tested prototypes, and wrestled with everything from buoyancy control to the ergonomics of pedal power.

Long hours in the workshop were matched by troubleshooting sessions in the test tank. They learned by doing, failing, tweaking, and trying again.

Competing in the eISR meant flying halfway around the world with their vessel and racing it in a submerged course against teams from top engineering schools. It was gruelling. The submarine had to be steered, balanced, and powered entirely by a human inside, while navigating underwater obstacles—all within a timed race format.

Despite the pressure and unfamiliar terrain, the Nautical Knights powered through race week. By the end of it, they didn’t just compete—they placed fourth overall. Not too shabby for their first attempt.

For Ryan, the experience wasn’t just about building a submarine. It was about proving what a determined, tight-knit group of students could achieve when thrown into the deep end.