All images courtesy of Alia Ballout

When I sit down for a chat with Alia Ballout, she’s almost sheepish about the arm sling she’s sporting after a particularly intense workout session.

“I went a bit too hard yesterday and dislocated my shoulder.”

She’s matter-of-fact. There’s a toughness in her that you don’t see in a typical 27-year-old Singaporean.

Perhaps it’s the sort of mettle you can only muster when you’ve watched bombs fall from the sky, just a hill over from your family’s home in the south of Lebanon.

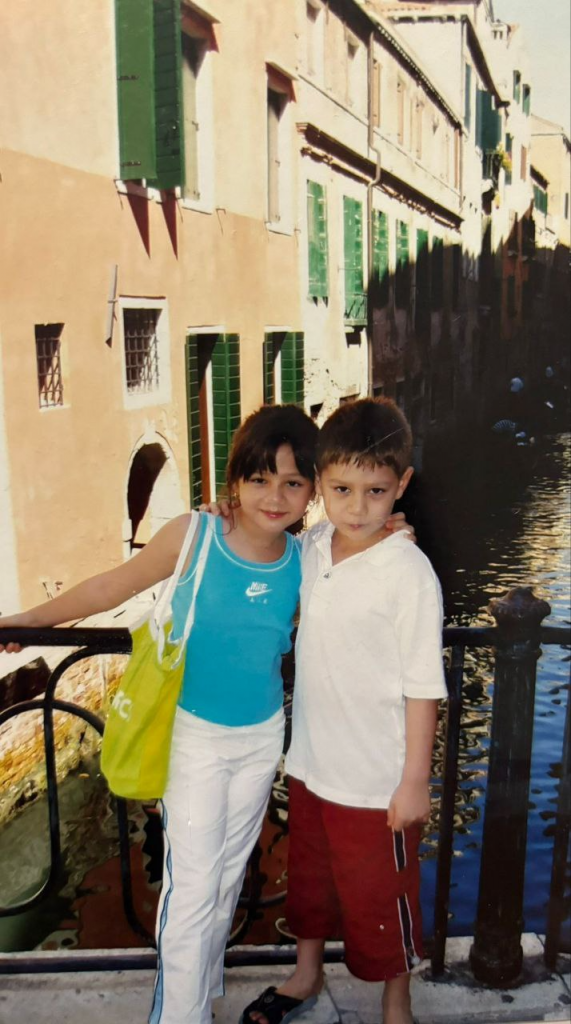

Alia is a passport-holding Singaporean citizen—but she’ll tell you she’s both Singaporean and Lebanese. Her mother, Mae Lam, was born in Singapore; her father, Adib Ballout, hails from Lebanon.

The family of four, Adib, Mae, Alia, and her younger brother, Alawi, shuttles between Singapore, Oman, and Lebanon every few months for school and work. Home is simply whichever country her parents are in, Alia tells me.

Together, they run Beît Ballout (pronounced bayt-buh-loot), their Singapore-based olive oil brand. Well, Alia runs it—the rest of the family pitches in to help.

Each bottle carries a piece of home, both literally and figuratively. The family hand-picks olives from their grove of hundreds of trees in Houmine El Tahta, in Southern Lebanon, and cold-presses them. The result is a rich, sweet oil. But Beît Ballout isn’t just making good olive oil. It’s a way of preserving and retelling their Lebanese roots, their culture, their people.

When we talk about Singaporeans settling in war-torn areas, or even anywhere that’s slightly less safe than Singapore, the reflexive response is: Why? The fact that a Singaporean would settle in someplace “less safe” becomes headline material.

But this isn’t that kind of story. Rather, this is about a daughter who’s bringing stories of her father’s Middle Eastern homeland to the Southeast Asian island where her mother grew up.

Escape to Oman

Mae, 58, tells me that she grew up in a conventional Singaporean household where, as she says, “boys were always favoured.”

It was the ‘60s, the era of Singapore’s two-child policy. Next to her academically inclined brother, who inherited her mother’s good looks, Mae says she felt like the black sheep of the family.

Her mother was a model and socialite, while her father was from a wealthy family in the pawn shop and diamond business. She remembers the constant need to prove herself.

“My big statement when I was young was always, ‘It’s not fair.’”

Perhaps it was her mother’s Shanghai roots, but traditional Chinese gender roles shaped life at home. Mae often ended up helping with the chores, while her brother wasn’t expected to. At the dinner table, the men of the family got first dibs on chicken drumsticks, a custom everyone accepted without much thought.

“Although we came from an upper-middle-class family, these little things do make you what you are.”

Her upbringing planted the seed in her—a nagging urge to explore beyond Singapore’s shores, away from her family.

Unlike her brother, she was an academic late bloomer, so she never gave her mother much to boast about. But her mother’s proudest moment was when Mae became a Singapore Airlines stewardess. It was prestigious and, more importantly, glamorous.

For seven years, she was a Singapore Girl. But as she reached 26, she realised she wanted more out of life.

Amid protests from her family—these would become a common fixture in her adult life—she quit her stable job at Singapore Airlines to enter the beauty and wellness industry.

Restlessness—and perhaps her intuition—later pushed her into a job based in Oman as a part of a private flight crew.

“I remember my mother crying at the airport and saying, ‘I’m losing my daughter. She is leaving a good job, and she’s going to be kidnapped by the people in the harem in Saudi Arabia,'” Mae recalls.

The idea that she was moving to the Middle East for work also stymied her brother and her friends.

“My brother was saying, ‘What are you doing to your life? You are 26. Are you crazy?’ But I said, ‘If I don’t do this, I will never know.’”

It was a choice that would change everything for Mae. On her very first day in Oman, at a birthday gathering organised by a colleague, she met the birthday boy who would eventually become her husband, Adib Ballout. Adib, a Lebanese, was working in the Oman Ministry of Energy and Minerals at the time.

“Was it love at first sight?” I ask.

“Not for me. I guess it was for him,” Mae laughs. “He said one day you’re going to be my wife. And he did propose after less than a month.”

Things fell into place because they were both ready to get married and have a family, she explains. They married secretly in Abu Dhabi, but kept it under wraps because it would violate her work contract.

Back in the ‘90s, a Singaporean-Lebanese marriage was anything but common. But Adib, then 35, had been married thrice before, so his mother was just happy he was getting married, says Mae.

Her family, however, was a different matter. Perhaps she knew innately her family, who’d already objected vehemently to her move to Oman, wouldn’t approve. So Mae got married without even telling them. It was only when her parents visited her in Oman months after the wedding that they found out.

She’d arranged for her family to stay in Adib’s home, telling them he was “a friend”. Then, she deliberately left their wedding photo album on the table.

“I left the album on the table and went to get them drinks. Adib almost had an anxiety attack, so he left and went outside. When I came back in, my parents’ faces were white.”

She pauses for a bit, knowing just how crazy the whole story sounds. “That was the only way that I could tell them. I didn’t know how to say it.”

Naturally, the rest of their two-week vacation in Oman was a little awkward. It also took them a long time to accept him. They wanted her to take the typical Singaporean route and marry a Chinese boy, says Mae. But she was determined to stay with Adib and raise a family in Oman.

The first time Mae visited Lebanon, she was already six months pregnant with Alia. She’d left her stewardess job to open a spa in a hotel in Oman. It was the ‘90s, and the civil war between Lebanon’s Christian and Muslim factions had only recently ended; the devastation was surreal.

“I had never seen buildings blown up into smithereens, and people still living there because it’s their home,” she recalls. “They had nowhere else to go.”

Lebanon was Adib’s home, but it quickly became clear that it was not the safest place to raise a family.

“We decided that Oman is going to be our base in terms of bringing up the kids. Lebanon was not for our safety. Singapore was not for our sanity.”

There, Mae’s kids went to an international school, surrounded by other third culture kids, far from Singapore’s stifling academic pressure. “If you don’t want tuition, it’s okay,” the mother remembers saying.

She wanted them to experience life and follow their own paths. “I always tell Alia that if you are timid and follow the standards others set for you, you will never know what can be.”

Nearly three decades later, she’s assured that she made the right decision to stay in Oman.

“I gave them the opportunity to study, to communicate, to develop themselves to where they want to be. I feel like my decision was the best thing that ever happened.”

Deep Roots

The foray into the olive oil business came later, almost by accident.

Despite the occasional bombings and enduring political instability in Lebanon, the Ballout family made it a point to return every few months, simply because it’s home.

“Life is such. Even if you go on a holiday, you can just drop dead, right? So we had to take a breath and go do it, because our home is there,” Mae says resolutely.

For Mae, leaving Singapore was an easy decision. So it’s almost surprising to see the depth of her connection to Lebanon.

She describes visiting the family cemetery after her father-in-law and sister-in-law passed away. “When I walked through, it’s not just his father—it’s generations of hundreds of years,” she says softly.

It’s a feeling I’ll only understand if I visit, Mae tells me.

“Lebanese and Palestinians, they never leave. They’re rooted to their land for thousands of years. That’s how strong they are.”

The land holds their lineage, their stories. And I get the feeling that those deep roots move her as much as the landscape itself.

“It is the most beautiful place—the sunsets, the sunrises. And whatever you put in the soil, it grows. It’s crazy.”

In 2018, the family bought a small plot of land near a hill. It’s common for families in the Levant—the eastern part of the Mediterranean—to have a few olive trees on their land, Alia tells me. Each family makes their own olive oil and shares it with their neighbours.

“If you have olive trees,” Alia explains, “you take the olives to the pressing plant—the messara. That’s just what people do.”

But the family only realised just how many trees they had after buying the house. The Ballouts now tend to nearly 500 trees. And their process is stubbornly traditional because Adib insists on it.

“No shaking of the trees,” Alia says. “I don’t know where he got that from—he just feels spiritually that you shouldn’t shake them. No pesticides. No chemicals. We only pick after the first rain when the olives are greenest and have absorbed the water, so they’re fat.”

These are his rules, and the family doesn’t deviate from them.

Mae’s contribution to the process is her Singaporean efficiency and meticulousness. After extensive research, she decided that the best time to press their olives is within four to six hours of plucking.

Before the family bought the land, they had only occasionally pressed the olives from Adib’s mother’s house. But they quickly became experts.

“We just throw ourselves into things first, then learn as we go,” Alia adds, grinning. “That’s very us.”

Unlike many European producers who use hot pressing for speed, the Ballouts stick to cold, slow extraction, even if it takes weeks.

“My dad was really against hot press,” Alia says. “He told us that cold pressing is how everybody did it—my grandfather and those who came before.”

Adib isn’t a man of many words, Alia tells me, but she guesses that his unwavering commitment to pressing olives the traditional way is his way of preserving his heritage.

But the trees hold deeper meaning still. The Ballouts grow Baladi olives, which are native to the region and common in Palestine.

“Through my Instagram, you’ll see real stories of Palestinian displaced people, stories of trees being burned,” Alia says. “In a way, growing these trees preserves their identity.”

To the people in the Levant, olive oil isn’t just a condiment. It’s culture and pride.

“People bring their own olive oil in their bags to restaurants,” Alia laughs. “They’ll take out their own oil and show off, saying, ‘We made this on our land.’”

From Law School to the Olive Press

Beît Ballout started simply because the family had too much olive oil.

“We used to give it away,” Mae says. “That’s when Alia said, ‘Why don’t we share it with the world?’”

It was 2023, and Alia was in the middle of her Juris Doctor (JD) degree in Singapore. But she was beginning to feel that law—and the rat race in general—was not the path for her.

The idea for Beît Ballout popped into her head during a particularly boring lecture about corporate law, Alia tells me.

“October 7 had just happened. I just felt like everything kind of just fell in place,” says Alia, referring to the Hamas attacks on Israel and the ensuing bloodshed in response.

As her social media feed filled up with images of ruins, rubble, and dead children, she felt an anger burning in her chest, Alia says. She felt the need to raise awareness of the suffering in the region—and to show people the beauty of the Levant that the relentless violence keeps erasing.

“The easiest way to spread awareness was through a product—you can get connected to the land, the people, the ground. You taste it and you know where it is from, and you have positive stories to tell.”

Like her mother, Alia followed her intuition. After finishing her JD degree, she left law—she even cut short a training stint at a prestigious local law firm—and threw herself into the olive oil business.

While her family handles logistics, Alia takes on everything from design to marketing to accounting. She’s even picked up two part-time jobs in Singapore (personal training and a sales role) just so she can sustain herself financially and keep her passion project going.

The family business is slowly making its mark—it’s been featured in Tatler, and has supplied its oil to Singapore restaurants like Popi’s, Wooloomooloo Steakhouse, Suzuki by Kengo Kuma, and Hashida.

But Alia shrugs when I ask her about all this.

“I’ve never been profit-driven. I feel like I’m put on this earth to retell stories. My marker of success is putting our little village on the map,” she says.

“Every dollar we earn, I want to put back into the village.”

Friends have asked her about scaling the business. But Alia candidly admits that she hasn’t thought about it. Her mission, she says, is to show the world the positive side of Lebanon—and for people to look past the conflict and violence to see its innate beauty.

Beît Ballout also gives back to the surrounding community by hiring Syrian and Palestinian refugees to pick olives each harvest season and paying them fairly. “If the market rate is $1 an hour, we’ll pay $5,” Alia says. “What’s $5 to us?”

Now, more than ever, there’s also a sense of urgency in getting her people’s stories out to the world.

As of publishing, the Israeli military has been stepping up deadly strikes across several villages in southern Lebanon, killing and wounding people in a Palestinian refugee camp while claiming they were targeting Hezbollah infrastructure. The fighting between Israel and the Lebanese militant group is still ongoing, with more than 4,000 people killed so far in Lebanon, including civilians.

In the back of Alia’s mind, putting her village on the map just might protect it from Israel’s bombings.

“Now, people are talking about the village. People will know that you aren’t bombing Hezbollah operatives. You’re destroying civilian lives.”

Between Two Worlds

As we’re speaking over video call, Mae is at the family’s home in Oman, while Alia is in Singapore preparing to bring Beît Ballout to Boutique Fairs, a lifestyle market running from November 21st to 23rd.

Alia readily admits that it’s sometimes a strange feeling shuttling between Lebanon and Singapore.

After all, just one month ago, she was in her family’s chateau in the south of Lebanon, watching bombs fall from the sky. She felt the entire house rumble. And when she ran outside, she saw the horizon light up.

The bombs had never been that close before. This time, it was just over the hill by their house.

Mae has been listening in as Alia recounts the bombing. “We embrace it, we accept it, and we kind of live with it,” Mae remarks quietly. “We can’t leave. We are not tourists.”

When they’re back in Singapore, however, it’s a different reality altogether.

“Even my mum, when she socialises with her Singaporean friends, she feels like they can’t relate,” Alia says. “It’s not their fault. We just get to go through two extremes, constantly.”

With Beît Ballout, Alia hopes to close that gap, even if it’s by a little.

“I just want Singaporeans to associate something positive with Lebanon,” she says.

“So the next time they see something in the news, there’s that moment of hesitation—that question of, actually, I don’t know if I agree with that.”

There’s a common saying about Lebanese people, Alia tells me: They rebuild no matter what, even when their homes are destroyed repeatedly.

“I don’t want them to keep doing that,” Alia says quietly.

“I want them to rebuild one time, and live life the way everyone else is living—like the way people live in Singapore.”