Top image: Tey Liang Jin/RICE Media

As Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin wrapped up the Committee of Supply debates last Friday, it drew the momentous Budget 2022 to a close.

From delayed GST hikes, the doubling of our GST vouchers, raising carbon taxes, and increasing the tax on the wealthy, the reception to Budget 2022 has been relatively positive—the usual rumblings on the ground notwithstanding.

ADVERTISEMENT

Those who are more well-versed with the Budget proceedings will tell you the budget debates that follow are arguably more interesting with more to chew on. Indeed, it has been. Still, in listening to the various speeches by MPs, an exceptionally befuddling point about the Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) was raised repeatedly.

After what seems like an endless discussion with my editor, we too are left scratching our heads, unable to come up with a plausible explanation for the endless back and forth.

In one of the latest measures of Budget 2022, Minister Lawrence Wong proposed a new minimum salary criterion for the WIS of S$500.

Adding to this, annual payouts for Workfare will be increased for each tier, the age group expanding to include those aged 30 to 34, and the income cap to be increased from S$2,300 to S$2,500.

The last three points make perfect sense in easing the difficulties low-wage workers face. However, implementing a minimum for receiving government aid is perplexing and perhaps signals a more significant change is afoot.

Fixing what is not broken

The WIS had its humble beginnings in 2007—a “broad-based measure that tops up the salaries of our lower-income workers and helps them save for retirement”.

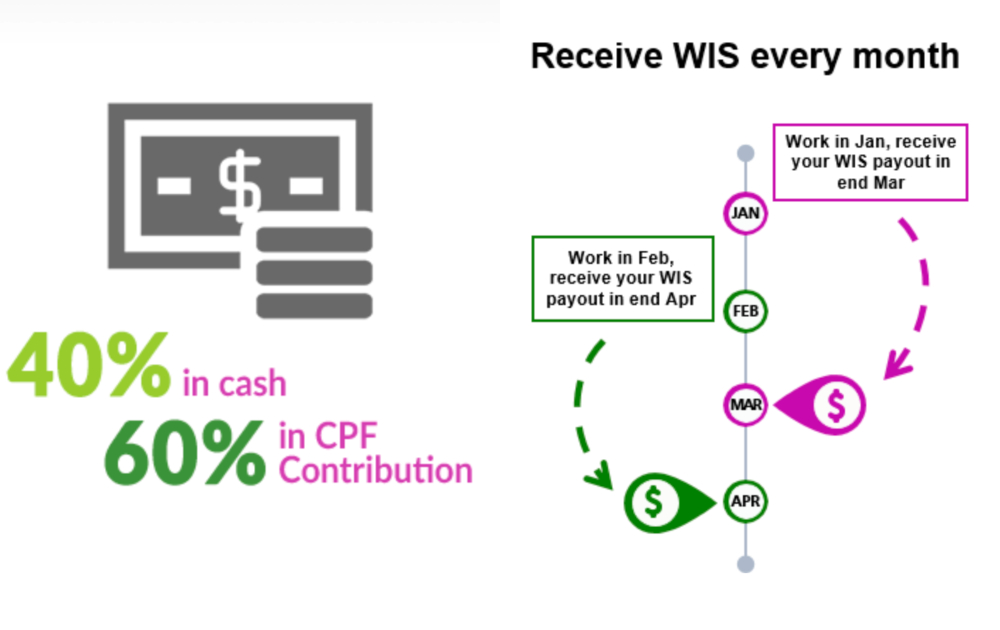

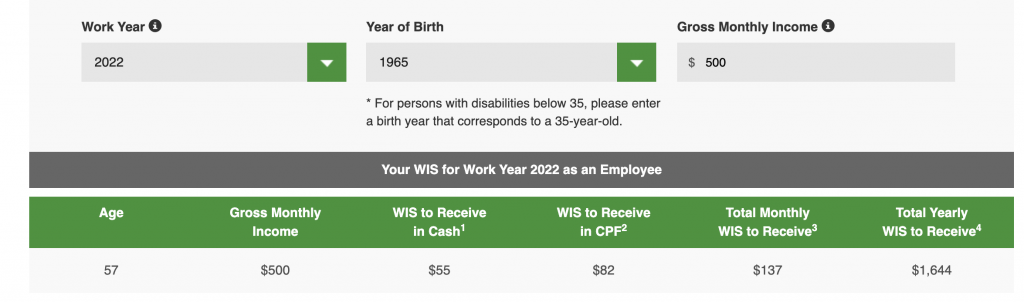

According to the official website, this scheme was introduced to assist and support Singaporean workers whose salaries are in the bottom 20%. Low-wage workers get their Workfare through CPF top-ups for retirement and cash payouts to supplement incomes. These payouts also differ by age group, older workers would stand to get a higher payout.

A worker who is 57 years old and earning S$500 per month will receive S$55 in cash every month, while S$82 will be contributed to their CPF.

Together with the Progressive Wage Model (PWM), these schemes should uplift low-wage workers while keeping employment levels high and unemployment levels low.

ADVERTISEMENT

In no small way, Workfare has done what it has set out to do.

As of December 2021, Workfare has disbursed a total of S$8.6 billion to over 964,000 low-wage workers. For a system that has been working so well for more than a decade, it is baffling that the government would now implement a new minimum criterion that might even potentially hinder those who need Workfare the most.

Full-time work is a privilege

Starting 1 January 2023, those receiving Workfare would have to earn a minimum of S$500 per month to qualify for Workfare payout. The main reason is to encourage casual workers or part-time workers to take up full-time employment. The intentions for this criteria might be sound but perhaps does not consider those who cannot take up a full-time job.

When it comes to jobs in Singapore, there seems to be a dichotomy between part-time and full-time work. In achievement-obsessed Singapore, clinching a full-time job is seen as a rite of passage and blueprint to live out a successful Singaporean life—whatever that measure of success means.

On the other hand, part-time work is often seen as temporary or a vocation for those going through transition periods in life, whether in school or between permanent employment.

We often forget that the ability to have a full-time job is a privilege in itself and that not everyone can hold a full-time job as much as they want to.

As the Leader of the Opposition, Mr Pritam Singh rightly points out, people who have part-time jobs “may be caregivers who do not have the flexibility to take up full-time work”.

Others, he adds, may not be able to stand for eight hours a day in a food & beverage setting for various reasons, including their advanced years.

This is an opinion seconded by PAP MP Jessica Tan of East Coast GRC, who cites how the new S$500 minimum “will impact older low wage workers or those who are caregivers and need the flexibility of part-time work”. She continues, “for this group of workers while they can and who do want to work, part-time work may be more suitable for them”.

Ms Tan cites an example of Mdm Lee, who works as a relief program coordinator at an Elder Care Center and earns as little as S$200 to a maximum of S$500 a month. Mdm Lee receives Workfare every month but is now worried she might lose the cash payout once the minimum of S$500 kicks in on 1 January 2023.

While many of us might see flexibility in a job as merely a work perk, for others, having job flexibility is crucial and a key determinant on whether they can have a job at all.

For caregivers, elderly workers, or persons with disability, part-time work presents as a viable option to accommodate their specific needs and earn a living. Ergo, Workfare comes in as a way to boost their current earnings should their circumstances prevent them from working that month.

However, the new minimum criteria of S$500 a month creates further pressure and anxiety to ensure they hit the minimum amount every month to get their Workfare. In trying to meet the minimum amount, these workers might feel compelled to take on more shifts than they can manage and cause more unnecessary stress.

As Ms Tan puts it, having these new criteria might very well negatively impact the very people it’s supposed to help.

Only 20,000 workers

As a response to the points brought up by Mr Singh and Ms Tan, Minister for Manpower Dr Tan See Leng counters that only a handful of about 20,000 Workfare recipients will be affected by the new criterion, all of whom are casual or part-time workers.

Dr Tan adds, “should any of these 20,000 workers subsequently work more and earn more than S$500 per month, they will automatically requalify for Workfare”.

“S$500 per month is a reasonable and achievable wage for most regular workers under our Progressive Wage Model approach,” says Dr Tan.

He further refers to the 46,600 workers Mr Singh had quoted, citing that this figure is not accurate and does not take into account the “wage growth from the Progressive Wage Model (PWM) expansion and new Local Qualifying Salary (LQS) requirements that would uplift many employees beyond the S$500 threshold”.

He added that those unable to earn S$500 a month due to their circumstances, including persons with disabilities and ComCare recipients, will still be provided Workfare payouts.

The new LQS requirement mandates that firms hiring foreign workers pay all their locals working part-time, at least S$9 per hour. With this in mind, Dr Tan asserts, “a part-time worker only needs to work about two working days a week to meet the S$500 minimum income criterion”.

20,000 is by no means a small figure, but compared to the 3.6 million residents in the workforce, it only makes up an almost inconsequential percentage of the workforce.

If this new minimum requirement is only going to affect a handful of workers, as Dr Tan asserts, it’s even more puzzling why there is a need to make any alterations to the well-oiled system in the first place.

“Gainful employment”

The small but rather considerable change to Workfare requirements while only affecting a small portion of workers is perhaps a more concerted push by the government to cement what “gainful employment” entails.

Senior Minister of State for Manpower Mr Zaqy Mohamad states that Workfare is not an endgame for those earning less than S$500 a month. Instead, Workfare boosts low-wage workers while they upgrade their skills to qualify for a higher paying job.

“For workers who are earning less than S$500, the best way to help them is to help them find a job of the appropriate quality and quantity of working hours to earn at least $500,” Dr Tan highlights.

It’s an adage repeated ad nauseam in support of upskilling and upgrading to attain a better job. While not grievous, it does set an unhealthy and unfair precedent that work can only become fulfilling if it crosses a certain financial threshold.

As reiterated by Mr Zaqy Mohamad, these changes are to “nudge all our workers, part-time and full-time, towards more gainful employment, so that we give them a higher sense of achievement”.

It’s an aspirational and seemingly innocuous statement, but with vague terms that belies the intentions of the statement. For some, what is “gainful employment” might look vastly different to others, and these nuances should be acknowledged.

If these workers already consider themselves to be gainfully employed—whatever their circumstances—it would be possibly damaging and disruptive to “nudge” these workers to constantly reach for more.

Furthermore, there is more to be gleaned from this ‘gainfulness’ as purported by Mr Zaqy. Salary cannot be the only indicator of meaning at work, and a sense of achievement is not derived from a generous paycheck alone.

An arbitrary number such as S$500 per month demands further explanation and elucidation as to why any minimum number is needed at all.

The biggest mystery of Budget 2022

This addition to the Workfare scheme is one of the more bewildering changes outlined in Budget 2022, only because we can’t be sure about the motivation behind this move. In recent years, there was no significant complaint or discernible public outcry about Workfare that would precipitate a change as monumental as this.

Moreover, from statistical and anecdotal evidence, it is clear Workfare benefited those under its scheme, no matter how small that number.

Still, the reasons offered by the government appear sound, but on further inspection, this new criterion creates more complications in the lives of low wage workers than it aims to solve. Yes, there might be a full suite of employment initiatives such as ComCare available, but getting these benefits might not always be a straightforward procedure.

This new criterion also suggests it might be a piece in a much larger picture we can’t yet see. Setting a minimum of S$500 per month seems to establish that figure as the floor for a kind of liveable wage in Singapore.

Could this be Singapore’s way of administering some sort of minimum wage with S$500 as the starting figure? Only time would tell.