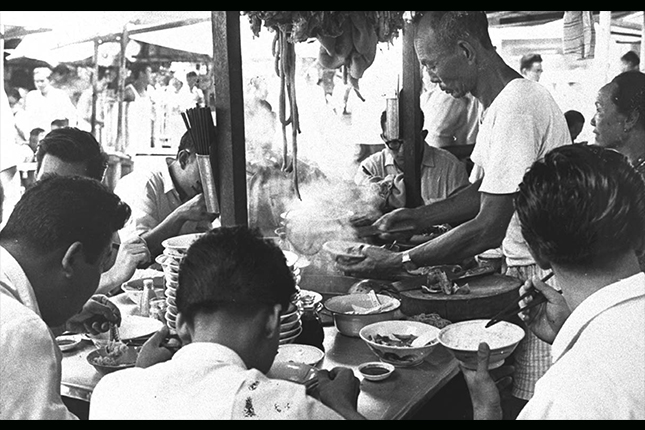

Not just any regular Pasar Malam, but one of Singapore’s oldest and most popular night markets. Born in 1958 with just 2-3 stalls, Woodlands Pasar Malam had expanded so quickly that by 1962, it was causing congestion trouble in Woodlands Village Centre. It proved so popular that the Straits Times published a feature on this new ‘Saturday Shopper’s Secret’, while Johor residents crossed the causeway in droves for bargains and food.

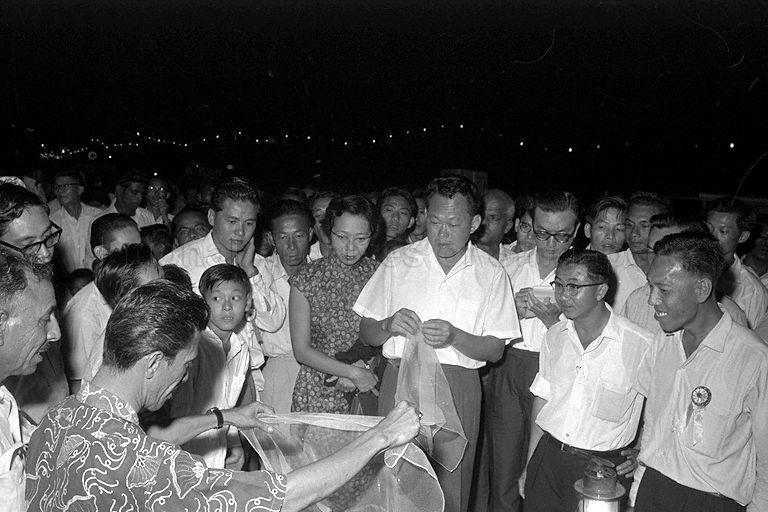

There is no record of whether LKY drank Bandung or Sugarcane, but Ah Gong was surprisingly salutatory about the night market. Despite his notorious aversion to disorder and his love of air-con, LKY praised the Woodlands Pasar Malam for “bringing goods to ordinary people”, and for “providing employment to large numbers of people who would otherwise be jobless.”

As early as 1962, they were identified as a menace in Parliament. By 1966, Operation Hawker Control was launched to license and regulate street-side hawkers. If they failed to register themselves by April of the same year, their goods and vehicles could be seized with no compensation.

By the end of the 1970s, the decline and fall of the Pasar Malam was complete. They were seen as noisy and polluting, they caused congestion, and they were a health hazard that might spread typhoid, cholera, and other transmissible diseases.

In 1972, there were still 56 Pasar Malams in Singapore. By 1975, everyone was off the streets for good.

The approximately 50,000-strong hawker population of the 1960s was halved to 24,845 licensed hawkers. People’s Park Pasar Malam—one of the busiest markets in Chinatown—was re-sited to make way for People’s Park complex. The older clientele faded away, replaced by a class of upwardly-mobile factory workers and undergraduates, who were drawn to the mall’s modern allure.

However, it wasn’t the government policy alone which killed the Pasar Malam. Car owners from the Automobile Association of Singapore complained because hawkers impeded vehicular traffic and caused safety problems for pedestrians who were forced off the pavement by hawkers.

Likewise, landed business owners complained of unfair competition from Pasar Malam hawkers eating into their business. Market-stall owners reported a 20-30% loss of sales to pavement hawkers, and some eating houses were apparently so hard-hit by the hawker/Pasar Malam competition that they were forced to shutter and become roadside stalls.

At the same time, Singapore’s Garden City branding exercise had just kicked in. It had no place for the polluting, disorderly Pasar Malam which was an ‘eyesore’ to the beautiful environments.

To the PAP’s credit, a number of MPs tried to lobby for the Pasar Malam’s return in parliament but their requests were denied for reasons of public health.

If the fate of nearby Pearl Bank Apartments is a sign of things to come, it would soon be a sleek Capitaland Mall with a Cold Storage in the basement and a Putien on the fourth floor.

However, the problem we face has not changed one bit. In the past, both hawkers and Pasar Malams were considered undesirable because they were chaotic, congested, and unsanitary. They were an obstacle to our nation’s aspirations to be a modern and civilised city. In the words of academic Elmo Gonzaga, they were a blight on the “legible image of stability and control” that was necessary for enticing foreign investment.

As a result, the relevant authorities are scrambling backwards to revive hawker culture and Pasar Malams as Unique Selling Points for Brand Singapore.

Cue product placement in Crazy Rich Asians. Cue paid-and-sponsored Michelin guides. Cue bids for UNESCO recognition—an effort that is surely equal parts preservation and promotion.

Desirable, demonised, and now desirable again, hawking has come full circle. Once upon a time, Brand Singapore sold itself on cleanliness and order. Now, we market the ‘passion’ of our citizens.

And therein lies the problem.

Our nation is adept at shaping and reshaping itself to accommodate the whims of foreign capital and globalising forces. When English was the lingua franca of business, everyone learned English at the expense of mother tongues. When China rose as a superpower, the government moved to promote SAP schools and Chinese culture. Arts and literature, once ‘luxuries’ we could ill-afford, are now marketed aggressively to make Singapore an ‘international arts destination’.

The same is true for our heritage. In the 1970s, Pasar Malams were demolished to make way for a modern Singapore, only to be brought back in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s to ‘re-vitalise’ far-flung town centres and tourist destinations like Sentosa or Boat Quay—albeit with mixed results.

Cc: Orchard Road’s anxieties about creating a unifying character that would not offend ‘transnational’ sensibilities.

Cc: Poet Amanda Chong’s 2017 speech about this very same issue in arts funding.

Cc: The ST Forum letter complaining about Little India’s messiness and a lack of tourist attractions.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with capitalising on culture for tourism. However, a purely utilitarian/instrumental approach to heritage and culture is not just shortsighted, but downright counterproductive.

What will happen to the hawker culture when ‘street food’ goes out of fashion in New York or London? Will we go back to Michelin imports? What if our heritage cannot be converted into monetary value in the here and now?

This is why I feel incredibly cynical about the campaign to make Hawker Culture into Unesco Intangible Heritage.

Despite the grandiose ministerial rhetoric, the lessons of history have not been learned, and we are still blown hither and to on the winds of transient global trends. Hawker culture might be preserved for the time being, but there is little compunction about saving Singapore’s old Jewish community buildings, or the Keramat Shrines, or the working studios of pioneering local artists like Chen Wen Hsi, or ecological heritage in Mandai. They are less marketable to an international audience and thus lower on the priority list—that is, until the day they suddenly show some capacity for profit.

At the end of the day, I support the UNESCO bid. However, we really need a more enlightened attitude to heritage and culture. If the history of the Pasar Malam can teach us anything about the future, it is that we should give us fewer fucks about cosmopolitan norms and international perceptions.

International opinions change every day. Our inheritance, once lost, will depart forever. No amount of STB public relations Black Magic will bring back the time when Malaysians crossed the causeway for food and retail.

Have something to say? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.