Selfies with famous landmarks? Only basic people visit tourist attractions nowadays.

Selfies with an ah ma whose groceries you’ve helped carry to the 12th storey because the elevator broke down? Yes please.

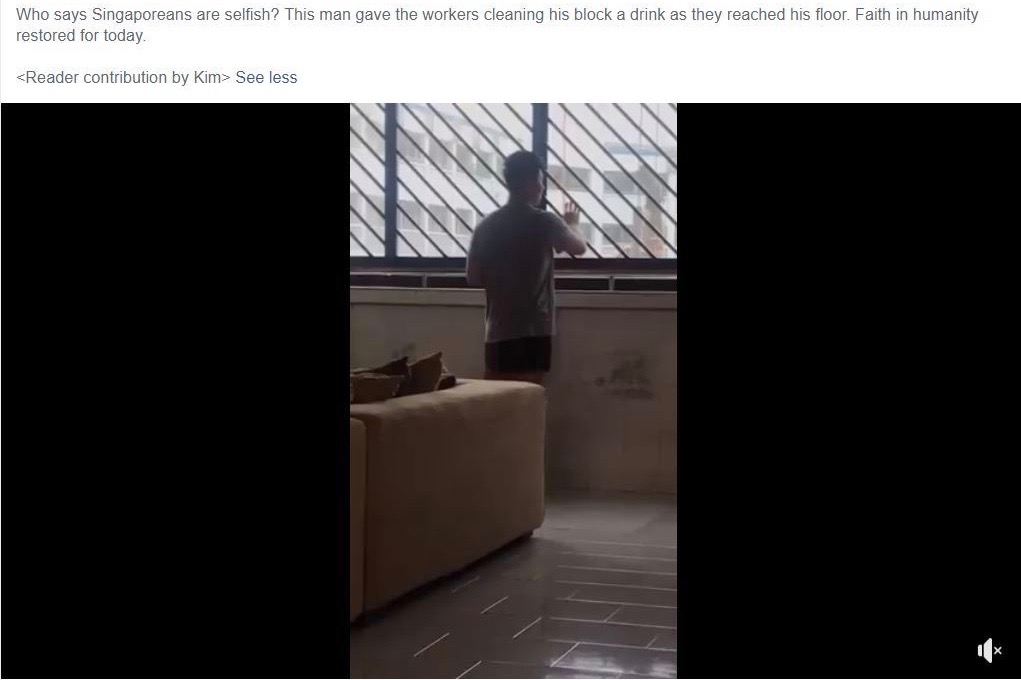

We all have that friend who, after carrying out a good deed, has to write a lengthy Facebook dissertation extolling the Virtuous Benefits of Kindness and lamenting the Degeneracy of Today’s Youths.

To top it off, the post will conclude with a selfie or video of them with their beneficiary, both grinning and beaming proudly. The post will then make its usual rounds on social media, and, if they’re lucky, the mainstream media will pick it up because such is what counts as news.

We wonder: why do such people feel the need to publicise their act of kindness? Isn’t helping someone else supposed to be a selfless act motivated by intrinsic rewards?

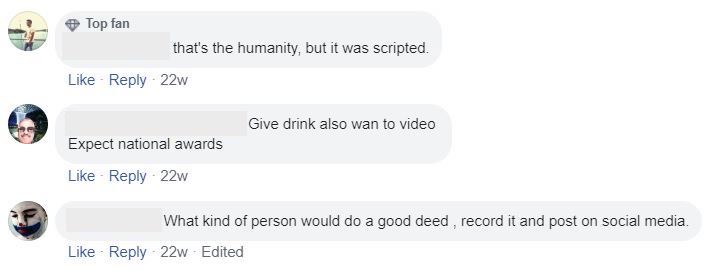

Then, our thoughts invariably turn towards the ultimate, and often unfair, condemnation: this must be an act of publicity designed to garner attention and likes.

Such a visceral reaction comes down to our repulsion towards virtue signalling. Just as we have grown cynical towards advertisements because we know their motivation lies in selling us shit we don’t need, virtue signalling is seen as an advertisement for something we don’t need to know. As James Bartholomew argues, acts of virtue signalling are “public, empty gestures intended to convey socially approved attitudes without any associated risk or sacrifice”.

Any open display—and, more fundamentally, publicity—of kindness thus makes us shudder.

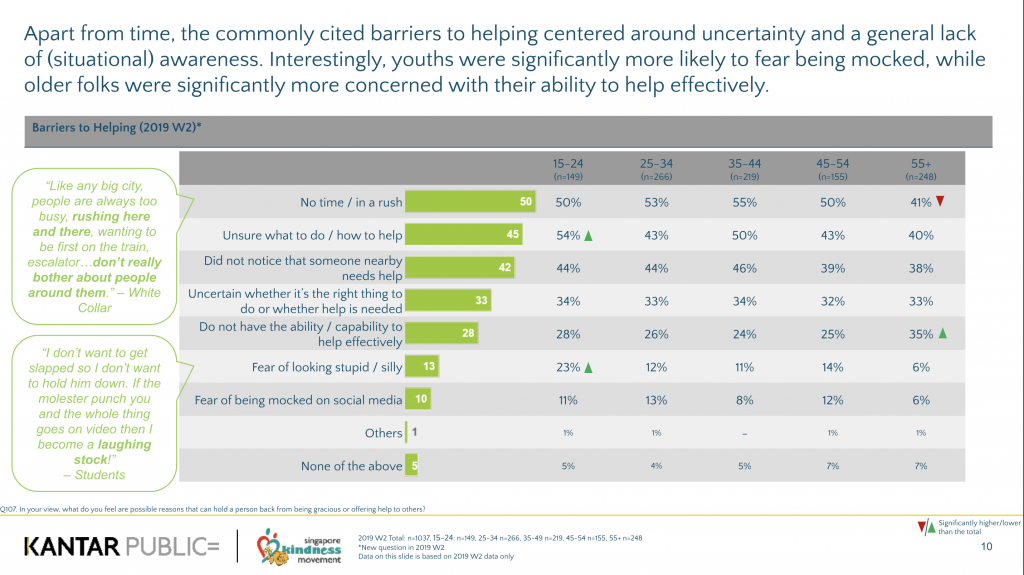

One in four Singaporeans between the age of 15 and 24 cited this as a reason why they would not offer help to someone in need, according to the Singapore Kindness Movement’s 2018-19 Graciousness Survey.

Could it simply be a cultural thing? After all, studies state that “people in the East actually experience and prefer to experience low arousal emotions more than high arousal emotions”.

To oversimplify it: we are not outwardly kind because we Asians are dead inside.

While this is certainly a contributing factor, fear is not a “low arousal emotion”. Fear is scary. Literally. Fear is motivated by an imminent threat or danger. What, then, is threatening about “looking stupid or silly”?

To answer that question, we have to ask: “looking stupid or silly” to whom?

To everyone on the internet.

Indeed, one example given in the report is a male student saying he would not intervene even if he witnessed sexual assault taking place in front of his eyes.

His reason:

“I don’t want to get slapped so I don’t want to hold him down. If the molester punch you and the whole thing goes on video then I become a laughing stock.”

Although such a response might seem exaggerated or even farcical—it takes a truly unkind society to mock someone who is thwarted in his attempt to stave off an attempt at sexual assault—it reveals the extent to which social media judgment affects expressions of kindness.

In other words, his fear and inertia to be outwardly kind are driven by the reaction of the social media hordes.

Yup, that’s you and me.

After all, publicly talking about an act of kindness you have performed is akin to humblebragging (i.e. shameful). This muddies the waters of what constitutes kind or moral behaviour, further diluting any wellspring of kindness that already exists in our society.

Therefore, every time we cynically deride a post describing whatever good deed the author has done, we potentially reduce the number of people who stand up for victims of sexual assault by one.

In this light, it seems that the real obstructions to kindness are people like us who pour scorn on virtue signalling. Who appointed us the role of the gatekeepers of kindness?

Furthermore, publicising acts of kindness and being authentic are not mutually exclusive. If every act of posting something on social media precludes genuine emotions, then all humans don’t love their dogs.

I don’t want to live in such a world.

Indeed, political theorist Sam Bowman points out that when we accuse someone else of virtue signalling, we are virtue signalling at the same time.

By saying that our annoying friend who posted their Good Deed of the Day on Facebook is virtue signalling, we are saying: we are virtuous enough to do our own Good Deeds silently.

Which is a paradox that also says: we’re the real assholes.